Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door (34 page)

Read Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door Online

Authors: Roy Wenzl,Tim Potter,L. Kelly,Hurst Laviana

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Serial murderers, #Biography, #Social Science, #Murder, #Biography & Autobiography, #Serial Murders, #Serial Murder Investigation, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Case studies, #Serial Killers, #Serial Murders - Kansas - Wichita, #Serial Murder Investigation - Kansas - Wichita, #Kansas, #Wichita, #Rader; Dennis, #Serial Murderers - Kansas - Wichita

Otis wasn’t the only person to note that the Seneca Street cereal box was found so close to Park City and to wonder whether BTK had killed two more people than the cops had acknowledged. Two days after the Seneca Street package was found, the

Eagle

published a story by Laviana and Potter pointing out the possible link between the Hedge and Davis homicides and the BTK case. They quoted former cops who said investigators had long suspected the Park City murders were related. Laviana, who had covered both homicides years before, wrote that Park City residents had gossiped about this link for years.

When Edgar Bishop saw the notice in the Home Depot break room, he came forward immediately, telling the cops about the Special K cereal box in the bed of his pickup two weeks earlier.

Bishop had thrown it away, but then he had gone on vacation�so his trash cart hadn’t been taken to the curb and dumped. He still had the package.

Otis and Detective Cheryl James delivered it to the FBI lab. They saw BTK’s description of how he intended to blow up his house with a propane and gasoline bomb if the cops entered it. That prompted a flip suggestion from Relph and Otis, who were still angry with the

Eagle

for showing up outside Roger Valadez’s house two months before. They joked that if BTK’s house really was rigged to blow up, the cops ought to invite the

Eagle

to go in first.

Landwehr smiled.

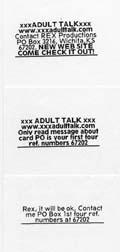

Much of the writing in the Special K box was the usual egocentric material. He liked to call himself “Rex,” Latin for “king,” for example. But the note labeled “COMMICATION” was intriguing:

Can I communicate with Floppy and not be traced to a computer. Be honest. Under Miscellaneous Section, 494, (Rex, it will be OK), run it for a few days in case I’m out of town-etc. I will try a floppy for a test run some time in the near future-February or March.

Was he serious?

Otis thought BTK was blowing more smoke. Gouge, Snyder, and Relph agreed. Did BTK think he could communicate with a floppy disk and not leave a trail? Was he stupid enough to think that the cops would “be honest” about whether a disk was traceable? Of course a floppy was traceable.

“He’s just playing with us,” Otis said.

“Maybe,” Landwehr said. “But we’ll try him out anyway.”

He prepared to place a personal ad in the miscellaneous section of the

Eagle

’s classified ads.

“Be honest,” BTK had written.

As a young cop, Landwehr had worked undercover, growing his hair to his shoulders, dressing sloppily, pretending to sell stolen goods. Landwehr had learned he was not good at undercover work because he was no good at lying. It wasn’t that he was opposed to lying to criminals; he was just no good at it.

But if BTK really was asking for advice about whether a floppy disk was traceable, Landwehr intended to lie to the best of his ability.

He sent Detective Cheryl James to the

Eagle

.

James told a classified ad clerk that her name was Cyndi Johnson. She gave a fake telephone number and said that she needed to run an ad for seven consecutive days, starting immediately. The clerk charged her $76.35.

The ad began as BTK has instructed: “Rex, it will be OK….”

The detectives fanned out all over town, checking UPC codes and visiting Dollar General stores to determine where BTK shopped for cereal and dolls. And the swabbing continued.

A code on the cereal box left at Home Depot showed that it came from the Leeker’s grocery at 61st and North Broadway in Park City�just north of Wichita�near I-135.

Tim Potter’s Marine Corps father had survived combat on Guadalcanal, Okinawa, and other Pacific islands in World War II. Potter learned that if he was patient, he could draw his father out and get him to talk about the brutality of war, along with its moments of humanity.

Landwehr communicated with BTK through the Eagle’s classified section.

As a reporter, Potter made a subspecialty of writing about trauma�when murders occurred, he sought out family survivors and asked them to talk. Unlike most crime reporters, Potter seldom swore, and never told macabre jokes. He wrote with insight about tragedy, using interviews with survivors to create mini-portraits of the dead. He had often been surprised at how willing survivors were to talk�it seemed therapeutic to them.

With the cops shutting down almost all comment about BTK, Potter had found other ways to write about the case between breaking news developments. He tried for months to get an interview with the owner of the Otero house. One day, she called him in desperation. Three days after the Seneca Street package was found, the

Eagle

published the story about her.

Her name was Buffy Lietz, and she and her husband lived at the corner of Murdock and Edgemoor. Around their little house, they had planted irises, roses, daffodils, and lilies of the valley. Potter was the first reporter she let into the tiny house. She had hung up on

America’s Most Wanted

five times until she finally let them in so that they would film their segments and go away. Kids had come to her back door and pressed their faces against the glass, even before BTK had resurfaced the year before. People parked across the street and stared. Pictures of her house had appeared on the Internet. She was sick of strangers coming by. “It feels creepy,” she told Potter.

She and her husband had bought the house years earlier without realizing it was a murder site. They just wanted to be left alone.

Potter felt ghoulish doing his job. He stood in the kitchen where BTK had confronted the family. L. Kelly had insisted that he must see the basement where Josie Otero had died.

When he asked Lietz if he could go down there, she said no.

The Home Depot parking lot at North Woodlawn had three security cameras. Landwehr, his detectives, and FBI agents studied the tapes until they figured out which truck in the busy lot belonged to employee Edgar Bishop. As they watched the January 8 tapes, they saw a series of images that they put together in the sequence of a story.

At first it was all blur, hundreds of vehicles pulling in and out.

But then they noticed something interesting: a vehicle circled the lot several times. At 2:37

PM

, a man got out of that vehicle, approached Bishop’s truck, and walked around it. It appeared that he might be writing down Bishop’s tag number. Then the man appeared to put something into the truck and walk away.

They rolled the tape backward, forward, backward, forward.

They traced the man back to his own vehicle.

Backward, forward, backward, forward.

They could not make out what kind of vehicle he drove. They enhanced the video. They analyzed the slope of the hood, the slant of the windshield, the reach of the wheelbase….

BTK drove a dark-colored Jeep Cherokee.

Detectives raced to the computers and checked motor vehicle records.

How many dark-colored Jeep Cherokees were there in the Wichita area?

Only twenty-five hundred.

With a few strokes on a computer keyboard, Landwehr’s detectives had dramatically narrowed the suspect list.

And on the video, for the first time, they had seen a glimpse of BTK.

On February 3, KAKE received a postcard in which BTK thanked the station “for your quick response on # 7 and 8” and thanked “the News Team for their efforts.” He said to tell the police “that I receive the Newspaper Tip for a go,” and promised “Test run soon.”

Landwehr planned to call the bomb squad and x-ray the next package before opening it. But that raised an additional problem: If BTK’s next package contained a floppy disk, would the X-ray scramble the information on it? The cops bought computer disks and checked them out. Tests showed the information would survive an X-ray.

Knowing that did little to relieve the burden Landwehr carried. At home, he and Cindy had finally brought some peace of mind to James, who had endured night terrors and slept in his parents’ bed with the light on after BTK had resurfaced. His parents had convinced him that BTK was too old and too careful to stalk the child of a police lieutenant who had patrol cars cruising past the house every hour. Landwehr was trying to stay connected to the boy despite his long hours on the job. Landwehr was still losing weight, or so the chief thought; his men thought Landwehr’s hair had gotten a lot grayer.

The renewed hunt had lasted ten months now. Landwehr was tired.

Rader was getting tired, too. His method of scaring people required work: write the message, being careful not to give away clues. Always wear gloves. Drive to a copy machine and copy the message. Then drive to several more locations to recopy it, often reducing the type. Recopying and trimming the edges of the paper made it harder for the cops to find which machines he used. He was tired of the driving around. He had a job and was still stalking women; it added up to time and effort. He was thinking of streamlining his tasks�which was why he had thought of the computer disk.

He used a computer at work, but he wasn’t terribly computer savvy. To be careful, he had made discreet inquiries, and had asked Landwehr. He thought the cops could not trace a disk.

He enjoyed the game with Landwehr. He knew Landwehr was talking to him, and he appreciated it. In the great, grand game that they played together, they matched wits, and the bad guy always won. He wanted it to go on forever, and he suspected Landwehr did too.

For a long time, single mother Kimberly Comer had lived in fear of Park City compliance officer Dennis Rader.

She had moved to Park City a year and a half ago, and soon noticed a little red truck with tinted windows. The guy inside took Polaroids of her and her kids. She thought he might be stalking her and her roommate, Michelle McMickin. McMickin called Park City police. But when officers came, they acted as if they knew who it was�and as if they didn’t care. Comer could not figure this out. Shortly after that, she actually met the guy. He was driving a white city truck and said he was the Park City compliance officer. He lectured her about belongings she had left in her carport.

Over the next several months, Rader handed Comer citations and warnings. Sometimes he put his head into her open kitchen window and looked around. He interviewed her children about her.

After she complained to Park City officials, he came more often. He claimed a 1995 Firebird she’d parked in her yard was inoperable. She got more rattled every time he talked to her. He creeped her out even after he did something nice for her kids. In early 2005, Comer’s children, eleven-year-old Kelsey and nine-year-old Jordan, were playing at a park. A big black dog began to bark and chase them. Kimberly was at home two blocks away.

Rader, driving by, saw the dog chasing the children, ran into the park, scooped up the kids, and put them in his truck. He took them to their home and gave them sticker badges and his business card. He was nice, the kids said.

But then he started harassing Comer about her “inoperable” car again. At the first Park City court hearing regarding her car a few weeks later, Comer drove to the city building. She told Rader her “inoperable” vehicle was parked outside. Rader declined to go look. Instead, he put his hand on her shoulder and told her she needed to take her complaint to the next court hearing. She walked away angry. He walked away unperturbed.

He had a lot on his mind. He’d been doing a lot of writing lately.

Within days of sending that message to the cops threatening to blow them up in his lair, Rader had accepted a position with Christ Lutheran Church in northeast Wichita as president of the congregation. The church member who asked him to take that position,

Eagle

assistant photo editor Monty Davis, admired him because he was hardworking and dependable.

On February 16, a receptionist at Fox affiliate KSAS-TV found a padded envelope in the mail, gaily decorated with seven thirty-seven-cent American flag stamps. “P. J. Fox” was the name on the return address. Within a short time, the television staff was calling the cops. A crew from KWCH-TV, which produced the Fox station’s newscast, took video of the contents: a gold chain and pendant, and three index cards�one of which told the cops how they should get back in touch with BTK through yet another newspaper ad. There was also a purple computer disk.

Gouge and Otis walked into the station minutes later, saw the stuff spread out on a table, and became impatient to take the items and leave. A disk! Could it be? Otis began to interview the receptionist, while Gouge talked to station managers, politely but bluntly telling them: “Do

not

broadcast any of the film you took here�and call Lieutenant Ken Landwehr before you do anything more. Do not broadcast or say anything about the disk.”

They agreed. Gouge did not want these people tipping off viewers that the cops were trading messages with BTK through newspaper ads, and he didn’t want it out that there was a computer disk from BTK now in police possession. If KWCH and KSAS broadcast that, the investigation would be compromised�reporters would immediately interview computer experts and BTK would learn that disks are easily traced.