Bing Crosby (20 page)

Authors: Gary Giddins

Electronic recording had been discussed for two decades, but it could not be implemented without a condenser microphone and

vacuum-tube amplifier. The need for wireless communication during World War I generated experiments that led to their invention,

yet at the end of the war nothing was done to extend their usefulness. Although singers like Bing depended on megaphones to

enrich and enlarge their voices, record companies saw no need to change their methods until declining sales signaled the need

for improved products. On Armistice Day 1920, the Unknown Warrior burial service in Westminster Abbey was transmitted electronically

over telephone lines to a recording machine in another building, an achievement that encouraged further tests. But still the

record companies declined to explore the possibilities — until 1924, when prototypes were built for electrical systems that

expanded frequency ranges in treble and bass, captured room ambience, and heightened dynamics. Even those improvements, developed

by Bell Laboratories, were resisted by the established record companies, which thought the electrical process too much like

their hated rival, radio. They capitulated within a few months.

The first electrical recordings were released in the spring of 1925. Many critics and musicians complained about distorted

sound that lacked the acoustic method’s purity. But modifications were made over the course of the year. Endorsements by Toscanini

and Stokowski, as well as Sousa, who had long since become an enthusiastic and well-paid endorser of records, helped convert

the skeptics. The Victor Talking Machine Company grandly designated November 2, 1925, Victor Day, to crown the blizzard of

publicity ballyhoo that preceded the launch of its electric Orthophonic Victrola. Within days Victor was swamped with orders

exceeding $20 million.

As noted, another innovation also helped pave Bing’s way. One of the most significant corollaries of electric recording was

the perfection of the microphone. In 1924 President Coolidge’s address to Congress was miked for broadcast, but beyond radio

and electrical records, microphones were rarely used in live performances. According to an old theatrical shibboleth, an entertainer

who could not project to the balcony’s last row was not ready for the big time; Jolson exemplified the leather-lunged belter

of songs. With the arrival of the microphone — and instant exit of the preposterous megaphone —

a new and more intimate kind of singing for larger audiences was made possible. Technology changed music. Ironically, mechanics

led to a more human and honest transaction between singers and their listeners.

Radio, which now rivaled the phonograph as the preferred mode of home entertainment, was on the verge of the first consolidation

of stations. Plans were under way to create a network of local transmitters linked by telephone wires. A year later, in November

1926, the National Broadcasting Company would make its debut, followed the next year by that of the Columbia Broadcasting

System. By the time Bing was ready for radio, radio was waiting for the voice made to order to showcase the closeness it could

provide. Motion pictures, too, were remade by the new technology. Twenty-four hours before Victor Day, with relatively little

publicity, Harry Warner — on behalf of the fledgling motion picture company Warner Bros. — bought control of Vitagraph and

its research into sound on film. Talkies would engender not only the movie musical but a subtler and more intimate style of

acting. Bing’s naturalness would fit in perfectly.

Victor Day found Bing and Al on the last lap of their mud-splattered journey to Hollywood, contending with an increasingly

wheezy engine and patched-up, withered tires. In later years they disagreed about many details of their epic three-and-a-half-week

road trip, but they differed little on the salient points: they sang nonstop while driving, worked when possible at parties

and roadside joints, and saved board money with an old show-business dodge — renting a single room and sneaking the second

man in after dark. Their stay in Seattle, early on, was auspicious. They boarded there with a friend of Bing’s from Gonzaga,

Doug Dykeman, who took them to the Hotel Butler to meet Vic Meyers, one of the best-known orchestra leaders in the state of

Washington. (Later he was better known as the state’s lieutenant governor, elected to his surprise with help from a facetious

campaign conducted by Larry Crosby, in which Meyers donned a white sheet à la Gandhi and promised to install hostesses on

streetcars; after his victory, he reneged.)

4

Jackie Souders led the Hotel Butler’s band that weekend, and Meyers asked him to give the boys a chance.

5

Meyers and Souders were each well established in Washington. Bing and Al had heard

their records broadcast in Spokane. Souders’s recordings from that time were representative of white jazz in the provinces,

with a passable rhythm section (de rigueur banjo and slap bass), clumsy instrumental soloists, and nasal tenors with small,

fey voices. The fact that the singers are more outmoded than the soloists and arrangements is in large measure a consequence

of Crosby’s impact. Soon he would put most of those singers out of work. Astute bandleaders in 1925 could not have failed

to recognize his lucid individuality. Souders agreed to let them show their stuff.

Al took his place at the piano, and Bing stood by him with a cymbal in hand. They sang in unison on the hot rhythm numbers

and featured Bing on a couple of Irving Berlin ballads. The college students, who regularly packed the place on weekends,

responded enthusiastically. Next to Bing’s full-bodied emoting, the singing of Souders’s regular vocalist, Walton McKinney,

must have sounded drearily anemic. Both Souders and Meyers made competitive offers to the duo to stick around and work with

their bands. Bing and Al discussed the bids that evening, but they were flush with their first triumph outside Spokane and

resolved to soldier on to Los Angeles.

By Al’s account they bypassed Portland, heading down the inland road through Oregon and the Siskiyou Mountains to California.

Bing, however, recalled hitting Portland as well as Medford, Klamath Falls, and San Francisco. On the way, they alternated

between fixing punctures and singing. Al wrote, “Bing would sing the melody and I would harmonize. The song ‘Dinah’ was one

of our favorites and we really gave it a good workout.”

6

But as they got closer to their goal, Al privately began to worry. He had never written his sister, Mildred, to tell her

they were coming and did not know how she would greet them.

Driving 1,200 miles down the coast, they tried to average 200 miles a day. On cold mornings the car would not start, and they

took turns with the crank. They went to a movie in Sacramento and were astonished at how much larger (2,000 seats) the theater

was than the Clemmer; they marveled at the lavish Fanchon and Marco stage show, with its dancers, singers, chorus line, and

emcee. “It was impossible for us to imagine, as we sat in that great big beautiful theater and watched those talented entertainers

perform, that in a few months we would be up on that same stage singing our songs,” Al remembered.

7

Next morning they reached the San Joaquin Valley,

driving past cotton fields and orange groves as the temperature climbed and then heading on to Fresno, Stockton, and Bakersfield,

where a gas jockey warned them it was ninety miles to Los Angeles, mostly mountainous, and their jalopy might not make it.

But what choice did they have? They switched into low gear and skulked the steep mountain road out of Bakersfield.

At the top of Wheeler Ridge, the flivver either blew and was abandoned (Bing)

8

or held up for the three hours it took to get to the outskirts of Los Angeles (Al: “We made it, but just barely”),

9

where they searched for Sunset Boulevard. They knew Mildred lived a couple of blocks off the thoroughfare, at 1307 North

Coronado. It was Saturday afternoon, November 7, when they walked up to her door and nervously knocked. A short, heavyset

woman answered and squinted at them for an uncertain moment until Al said, “Don’t you know me? I’m your brother Alt.” They

had not seen each other in nearly three years. “[Mildred] let out a holler and put her arms around me. She was so surprised

she couldn’t believe it was me.”

10

Al introduced Bing while noting silently the weight she had gained. They described their trip and their ambitions, and she

offered them a spare bedroom, suggesting that they store Bing’s drums in the cellar (where they remained until he sold them

a few weeks later). As she prepared lunch, Mildred asked Al about their father and his new wife, Elsa. Al reassured her of

their happiness and said that Elsa was taking good care of their brothers. Mildred, in turn, told him about her husband, Benny,

who was doing well in the bootleg business. As for herself, she was singing at a speak near Hollywood operated by a friend

of hers, Jane Jones. After describing the high-class customers and good tips, she invited them to tag along.

At twilight Mildred, whom Bing instantly took to calling Millie, made cocktails and asked them to sing. In a flash they were

at the piano. After a couple of tunes, she walked over and hugged and kissed each of them. “You guys are great,” she said.

“You should have no trouble getting something going for yourselves.”

11

After another drink they asked her to sing. Millie sat at the piano and sang Irving Berlin’s “Remember” and Nora Bayes’s

old hit “Just Like a Gypsy,” with, Al recalled, “the same feeling and style which later on would make her a star. I could

see that Bing was really impressed, and I was very proud of my sister.” Benny Stafford returned in time for dinner and then

drove them to Jane Jones’s speakeasy in the Hollywood Hills.

12

The boys liked Benny, thought him “a regular guy”

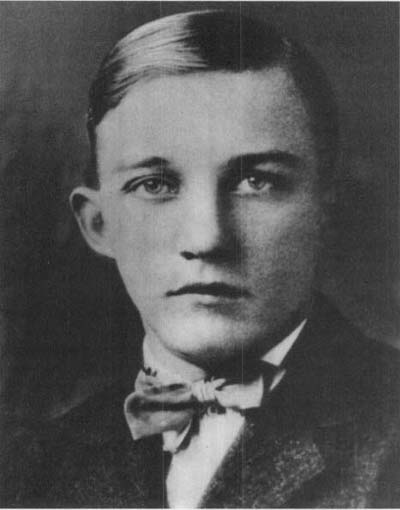

Bing Crosby graduated from Gonzaga High School with a diploma in classical studies in 1920.

Mark Scrimger Collection

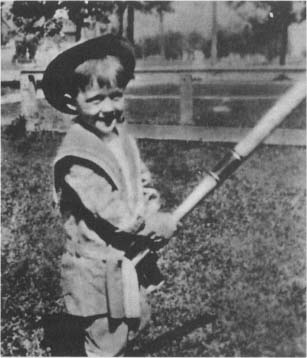

Bing practicing his swing at age four.

Mark Scrimger Collection

Bing’s mother, the former Kate Harrigan, during the years in Tacoma.

Mark Scrimger Collection