Bing Crosby (72 page)

Authors: Gary Giddins

Jack Kapp, Joe Perry, and an engineer listen from the recording booth as Frances Langford, Bing, and Louis Armstrong record

the

Pennies from Heaven

medley, August 17, 1936.

Elsie Perry Collection

The Boswell Sisters alternated with the Mills Brothers as regulars on Bing’s Woodbury radio show. Bing later recorded famous

duets with Connie Boswell, center.

Ron Bosley Collection

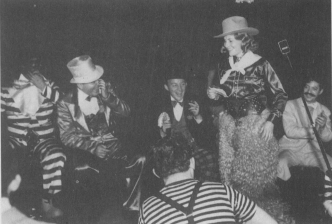

ABOVE: The Crosbys’ Westwood Marching and Chowder Club minstrel shows were major Hollywood social events in the late 1930s.

Bing poses with (left to right) Bessie Burke, Midge and Herb Polesie, Dixie, and Johnny Burke. BELOW: Seated with an unidentified

blackface actor, Pat O’Brien, and Jerry Colonna, Bing enjoys Bessie Burke’s backless chaps.

Rory Burke Collection

Bing takes the baton from bandleader and songwriter Harry Owens, after “Sweet Leilani” became the surprise hit of 1937 and

helped turn Los Angeles into a Hawaiian theme park.

Len Weissman/Elsie Perry Collection

At which point the band struck up a loud and hasty introduction for her song.

Bing kept clear of the commercials, segueing with a line like “And here is Ken Carpenter to say a word on behalf of the management.”

Then he sang his first song, backed by Dorsey’s “swanky swingsters.” No matter what the song, Bing sang with his accustomed

rhythmic lilt when Jimmy or his sub, Joe Venuti, led the band. Then he would trade a few lines with Bob Burns, whom Bing usually

called by his given name, Robin. Burns would do seven or eight minutes about his relatives — the drunk uncle, the shrewish

sister-in-law — and close with a bazooka solo. Frequently the patter with Burns or another guest would produce an uncommon

word, like

bauxite,

that recurred as a comic motif throughout the show. One Crosby segment created a tradition, imitated on radio and TV: he

would offer a few clues to a bygone day and give the audience the space of a station break to guess the correct year. Then

he sang a representative song. On this show the year was 1928, and the song “June Night.”

Time now for the second guest, George Raft, who spoke of his big break in

Scarface,

plugged the picture he was currently filming, and talked baseball — all very informal, very scripted, with a few inside curves:

Raft: Who’s taking care of the store now?

Bing: You mean the studio? Paramount?

Raft: Yes. Any changes made since I’ve been away?

Bing: Oh, A. Zukor’s back in charge.

Raft: You mean that racehorse, Azucar?

Bing: No, no — Adolph Zukor, the little giant. He’s running things now.

Raft: Oh, I see. Say, what’s this gag about bauxite? All I’ve heard since I’ve been here this evening is bauxite. What is

the stuff?

Bing: I’ll tell you, George. I’m going on location Saturday and you’re going tonight. When I come back and you come back,

there may be some report from the research committee. I’ll tell you then.

Then Bing sang, sometimes a medley and sometimes one of his current records, but often not. The few surviving recordings of

the 1930s Kraft shows are treasured not least because he never formally recorded more than half the songs featured on the

air, including

dozens of good ones, like Berlin’s “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket” and Ellington’s “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart.”

Next came the longhair spot. Bing introduced Seidel with straightforward biographical remarks, noting his Oslo debut, his

first American visit, and his 1,100 recitals, winding up with a peculiarly Crosbyan verbal turn, starting high and landing

low: “Mr. Seidel favors us this evening with the scherzando movement from Lalo’s violin concerto

Symphonie Espagnole,

and when you hear Mr. Seidel play it, if you don’t think it’s swell music, then you can’t pick tunes for me.” After the number,

they talked a minute. Seidel was eager to get back East for the fights:

Seidel: But before I leave for New York, I’d like to know what bauxite is.

Bing: I’d be glad to tell you, but later. I don’t want Burns to hear.

Seidel: Well, I’ll wait around then.

Bing: And while he’s waiting around, ladies and gentlemen, Toscha Seidel plays as an encore a composition by one of his colleagues,

Fritz Kreisler’s very lovely “Schôn Rosmarin.”

That number was followed by a combo from the Dorsey outfit playing an original jazz riff, “Coolin’ Off.” The show was winding

down. After the third and final commercial, Burns explained to Bing that bauxite is “a ferruginous aluminum hydroxide,” spelling

the chemical equation. Bing, in what was often the hour’s high point, settled into a ballad — tonight, “The Touch of Your

Lips.” He then named the guests for the next week’s show as “Where the Blue of the Night” swelled behind him.

The show’s most caustic critic was invariably the director. Kuhl described the May 7 program as “O.K.,” before laying on his

comments. Bing was on top of the mike again: “An elephant never forgets and a Crosby never remembers,” he wrote in his report.

The show suffered from “spring fever” and lacked “the usual pep, pace, and vivacity.” Merkel was good, but she “should learn

to play comedy.” Raft had no material. Kuhl worried that Bing came across as “disrespectful of Seidel, a la Jolson” and thought

he had trouble with the key on one number. He considered only Burns to be “very good.” Even a cheese promo left a bad taste:

“Kraft couples carry on the silliest conversations.”

33

Kuhl’s reservations were shared by few listeners.

* * *

Friends noticed that real Bing and radio Bing were sounding more and more alike, the former catching up with the latter. It

was as if the object of Carroll’s study had been liberated by the resulting caricature. Predilections stressed in his scripts

were embraced by Bing, and he became indistinguishable from Carroll’s takeoff. Put another way, Bing got a better sense of

who he was from the role he played. In publicist Gary Stevens’s analysis, “Carroll gave Bing the suavity, savoir-faire, the

throwaway personality that Bing never had, and Bing lived that part for the rest of his life.”

34

To Eddie Bracken, “Carroll’s wonderful fey way of writing just fit Bing beautifully and literally made Bing a better actor.

Carroll gave him a type of characterization different than anything else on radio and also different for Bing.”

35

To Bing, Carroll’s influence was comparable to that of Jack Kapp: “He’d send a script around to my home and I’d try to rewrite

the speeches he’d written for me so as to make them sound even more like me. And I’d try to put in little jokes if I could

think of any. Most of them were clumsy and pointless, but once in a while I hit something mildly amusing and Carroll wouldn’t

delete it if he thought it had a chance of getting a laugh. The way we worked together resulted in the next best thing to

ad-libbing.”

36

But the next best thing was not good enough. To keep things lively, Carroll encouraged Bing to ad-lib a little, even if just

an impromptu laugh — an infectious burbling that audiences loved. Observing how verbally dexterous Bing could be with his

friends, Carroll was confident of Bing’s ability to stand his ground and quip with the best. At first, with Kuhl’s support,

Carroll encouraged safe ad-libbing, the kind that takes place in rehearsal; if Bing (or a guest) came up with a zinger, it

was written into the script. Carroll soon devised the subterfuge of handing Bing a slightly different script than that of

his guests. The first time he tried it, he simply had a guest inquire about Bing’s latest golf score. The studio went dead

for a moment as Bing paled before finally responding, “Why, about eighty-two.” When the guest asked another surprise question,

Bing said, “Let’s get back to the script here.”

37

He had a fit when the show ended, threatening to quit when Kuhl told him to expect more of the same. He got used to it, however;

his nervousness abated, and he began to sound more like himself. When Mischa Levitski made his third

KMH

appearance, the repartee began with Levitski remarking that he played better in the Music Hall than anywhere else because

he could dress informally.

Bing: I’m delighted to hear it, and may I say that all day long I’ve been admiring your splendid red suspenders.

Mischa: A great many pianists wear suspenders exactly like these.

Bing: Any reason?

Mischa: Yes. To hold up their pants.

38

The joke was older than vaudeville, a cousin to minstrelsy’s road-crossing chicken, yet it generated an enormous response,

in part because Levitski was delivering it, but chiefly because Bing did not see it coming and cracked up. His script read,

“Because the flannel is soft and doesn’t cut into the shoulders the way elastic suspenders do.” Radio laughter galvanized

audiences with its titillating suggestion of an indiscretion, especially Bing’s, for he was almost always unflappable.

Kuhl marveled at Bing’s ability to pilot the show no matter what the obstacles, sometimes sacrificing his own numbers. “Drastic

cutting, late in the game, hurt show,” Kuhl noted of one program, “but not as much as if Bing with typical, Quixotic gallantry,

hadn’t insisted Avalon Boys do two numbers at expense of his own medley, which we cut.”

39

When Bette Davis’s segment was shortened for time, Kuhl wrote, “an ad-lib of Bing’s” (unpreserved) saved John Reber “the

price of orchids.”

40

At times, Bing’s ad-libbing proved “the only way out when the free speech of the show gets beyond control — and it’s the

free speech that makes the show.”

41

After

KMH

had been rolling for a few months, the

New York Post

radio columnist observed that what began as “a slightly casual touch” quickly “crystallized into an attitude of catch-as-catch-can

good humor,” adding that no other show could so ingratiatingly offer artists of the caliber of Harold Bauer and Lotte Lehmann:

“Mr. Crosby presents them not as something that the audience ought to like but as something that the audience will like.”

42

Bing’s presumption flattered his listeners. Their presumption that he was one of them, despite his much publicized prosperity

in times of economic woe, flattered Bing. Movie-star wealth was an ancient story by the mid-1930s — the fantastic estates

and servants and blocklong cars, the yachts and exotic playgrounds. But on Bing, who so obviously enjoyed his good fortune,

it looked good, providing vicarious pleasure for his fans, as well as a measure of proof that the system — America itself

— was not in irreversible decline.