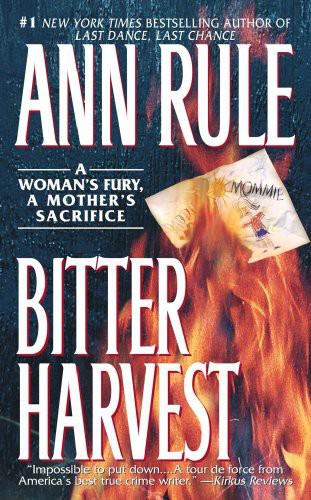

Bitter Harvest: A Woman's Fury, a Mother's Sacrifice

Read Bitter Harvest: A Woman's Fury, a Mother's Sacrifice Online

Authors: Ann Rule

Tags: #General, #Murder, #True Crime, #Social Science, #Criminology

Originally published in hardcover in 1997 by Simon & Schuster Inc.

| A Pocket Star Book published by |

Visit us on the Web:

http://www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 1997 by Ann Rule

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For information address Simon & Schuster Inc., 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN 13: 978-0-7432-0278-7

ISBN 10: 0-7432-0278-3

POCKET STAR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

to Bonnie Allen of Roslyn, Washington

Teacher, artist, and my friend for three decadesyou have overcome tragedy and adversity andremained the embodiment of whata mother and a grandmother can and should be

God Bless

BITTER HARVEST

CONTENTS

S

ometimes the places where searing tragedies have happened are marked with visible scars. More often, when normalcy returns, only the most discerning eye or the most sensitive mind will know. This is the way the world is and must be; we cannot forever grieve over old wounds and ancient sorrows. New grass covers bare ground, and flowers come back in the springtime, no matter what has happened on the earth that nurtures them.

Prairie Village, Kansas, became one of those places where an unbearable, irredeemable tragedy occurred. Something terrible happened there on a windy October night in 1995, a catastrophe of such magnitude that it seemed that the street where it happened—Canterbury Court—could never recover, that no one living there could ever laugh again. And yet, when I walked along Canterbury Court long after the wildfire that had erupted there, I saw no sign that anything unusual had taken place on that quiet suburban street.

People who live in other parts of America often don’t realize that there are

two

Kansas Citys, one on the easternmost border of Kansas and the other on the western edge of Missouri. If they were sisters and not cities, the former would be an independent cowgirl, and the latter a graceful patron of the arts. Natives of each state seem to differentiate between the two with no difficulty whatsoever; they call one KCK and one KCMO. However, two cities with the same name create much confusion for visitors. Kansas City, Missouri, with a population of 450,000, is three times as big as its Kansas counterpart. Ward Parkway, in Kansas City, Missouri, is lined with beautifully landscaped homes and estates and has a proliferation of statues and fountains. Kansas City, Missouri, has opera and ballet companies, and quaintly restored shopping areas whose original glory days were sixty or seventy years ago. At Thanksgiving, thousands flock to the Country Club Plaza to see the tiny lights that outline the old stucco buildings turned on. Instantly, the picturesque plaza becomes a holiday wonderland. Residents in “KCMO” live “north of the river” or “south of the river”—meaning the mighty Missouri.

The Missouri-Kansas border—State Line Road—runs south from the confluence of the Kansas and the Missouri rivers where they become one: the Missouri. Indeed, in some areas the state line is the center of the Missouri River. Thousands of families live in the Johnson County, Kansas, suburbs of the metropolitan Kansas City area and commute to Missouri. Visitors to both cities fly into KCI, a shared airport on the Missouri side. The gift shops sell souvenirs of Kansas’s most famous—if fictional—characters: Dorothy, Toto, the Cowardly Lion, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man, all the beloved players in

The Wizard of Oz

.

Johnson County is in Kansas; Jackson County is in Missouri. Johnson County has 430,000 residents and is one of the most sought-after areas for upwardly mobile families. The Shawnee Mission Parkway rolls west from Kansas City, Missouri, and intersects with I-35, which turns south—a feeder freeway to myriad communities with tree-lined streets and homes built for pocketbooks ranging from modest to sumptuous: Roeland Park, Leawood, Mission, Fairway, Mission Hills, Merriam, Shawnee, Prairie Village, Overland Park, and, some thirty miles down the line, Olathe, the Johnson County seat. Many of these towns actually straddle the state line; homes just across the street from each other are in different states. Police jurisdictions intermingle, as do fire departments’ perimeters. More than in most areas, cooperation between agencies is essential.

Of all these suburbs, Prairie Village is probably one of the most desirable (second only to posh Mission Hills), although its name scarcely describes its appearance. There is no prairie, and this is not a village but an upscale haven for professionals, with more doctors, lawyers, CEOs, and others with incomes well over $100,000 a year than almost any town in Kansas. Many of the houses in Prairie Village are “old money” classics of brick, built in the thirties or earlier. One small development, Canterbury, with its Canterbury Court and Canterbury Cul de Sac et al., is clearly “new money,” its mansions expensive imitations of English Norman, baronial Georgian, and Frank Lloyd Wright modern. Canterbury Court opens, somewhat incongruously, onto busy West Seventy-fifth, with its smaller homes and apartment houses.

It is an orchid dropped among dandelions and daisies—exquisite but out of place. Few of Canterbury’s privileged children go to public school; rather, they are driven to private schools like Pembroke Hill, whose tuition is prohibitive for the average working family. Schoolchildren who live one block on either side of Canterbury sometimes tease the “rich kids.”

In the mid-nineties, every other house in the first block of Canterbury Court seemed to house a doctor—or two. Mom-and-pop docs, as it were. And for someone who had grown up in a working-class family in a rural town, one mansion on Canterbury Court marked the pinnacle of achievement. A three-floor, 5,000-square-foot house with a swimming pool, it was meant to be a house to mend a marriage, a perfect home to solidify a family torn apart—a place to begin anew. But as a dread scenario unfolded, it became a house of horror.

When I first stood in front of what once had been 7517 Canterbury Court (the numerals still visible on an elm tree), it was January and desperately cold. I found it almost impossible to imagine that sheets of fire had consumed the house, flames fanned by autumn winds until they were higher than the treetops. In deepest winter, the ground was frozen solid; the huge maples and elms were bare. Even the blue spruce trees drew into themselves against the cold. Only a copse of seven or eight fragile white birches seemed alive. Incredibly, they had survived despite the heat that caught them in a deadly embrace, searing their bark and curling their leaves. The spring rains might revive them.

Blizzards had come and gone, leaving a light dusting of snow over the brown grass and ice-hardened ridges made by some heavy vehicle driving through mud. I had to look closely to see that the small rocks at my feet were not rocks at all, but cinders, charred fragments plowed into the earth. That was all. There was no “For Sale” sign on the vacant lot, no yawning burned-out foundation, no blackened boards, no reminder of what had once been there. It was all gone—along with the hopes and dreams of the five human beings who had lived in the house that stood on this lonely place.

The neighbors’ leaded windows and heavy doors were shut tightly against anyone with questions. They were as impenetrable as the houses’ stone and brick façades. No one wanted to remember that windswept October night when there were screams and sirens and, finally, only the muted voices of firefighters moving with a kind of organized desperation.

By that time, there was no longer any need for haste.

When I revisited Prairie Village and Canterbury Court six months later—in July—the vacant spot between the two closest houses looked like a park. The grass was bright green and the trees made a canopy of leaves that cast long shadows on the lawn. There was nothing alive there, and that haunted me because, in the interval between visits, I had learned the details of what had happened nine months before. The adjacent houses seemed to have edged stealthily together as if to pretend that no structure ever stood between them—certainly nothing as massive as a stucco and fieldstone mansion with a four-car garage.

The children who lived in the neighboring houses woke less frequently from their fiery, wild-eyed nightmares now that summer had come. Their parents turned away from reporters and gawkers; they had told what they had to tell in a court of law. They wanted only to regain the safe feeling Canterbury Court once offered. They wanted to forget.

But, of course, none of them can really forget. Not ever.