Bittersweet

Authors: Peter Macinnis

Bittersweet

Bittersweet

THE STORY OF SUGAR

Peter Macinnis

First published in Australia in 2002

Copyright © Peter Macinnis 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act

1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10% of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:Â Â Â Â (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â (61 2) 9906 2218

Email:Â Â Â Â info@allenandunwin.com

Web:Â Â Â Â Â Â

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Macinnis, P. (Peter).

Bittersweet: the story of sugar.

Bibliography.

ISBN 1 86508 657 6.

1. SugarâHistory. 2. Sugar tradeâHistory. I. Title

633.6

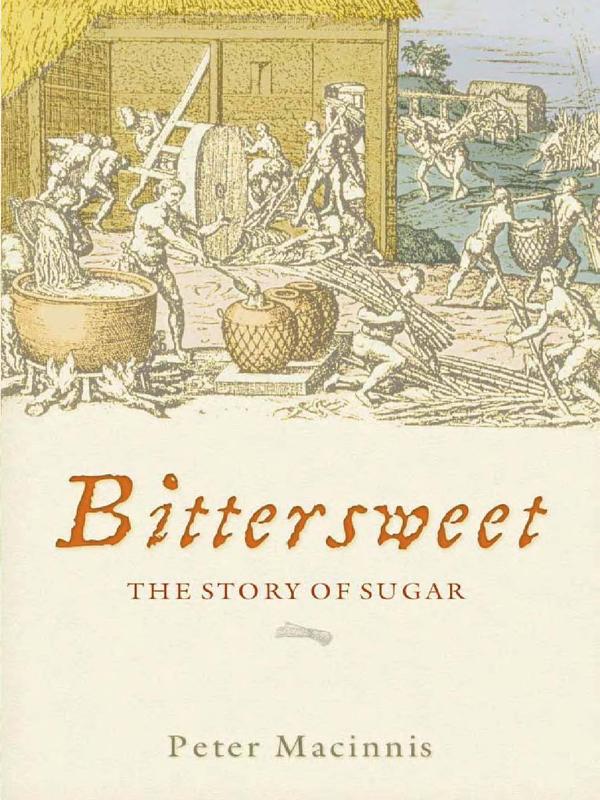

Cover by Liz Seymour

Cover illustration: Theodor de Bry,

Collections peregrinatorium

, 1595

Chapter illustration: Jacques Dalechamps,

Historie générale des plantes

, 1615

Maps by Ian Faulkner

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

Printed by McPherson's Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Note on measurements and money

4 The English and the Sugar Business

8 The end of slavery in the Americas

12 Sugar in the twentieth century

Epilogue: The costs and benefits

P

eter Macinnis was born in Queensland, Australia, but grew up on Sydney's northern beaches, where he still livesâand where he is a somewhat obsessive bushwalker. After several years tending ledgers in the 1960s, he decided it was better to be a biologist than an accountant and obtained a bachelor's degree in botany and zoology. As well as being a husband and father of three, Peter has worked as many things: science teacher; education officer for the state department of education where he eventually became Principal Education Officer and number cruncher (as well as gaining a Masters in Education); and he was later an educator with both the Powerhouse and the Australian Museum before returning to the classroom for a number of years. In 1999 Peter began writing full-time for WebsterWorld, an online encyclopaedia, and continues his work there today.

Over the years, Peter has written or co-authored some twenty books, mainly for children or schools, as well as presenting talks on ABC Radio National since 1985, appearing on âScience Bookshop', the âScience Show' and, most frequently, on âOckham's Razor'. Peter has a large science web site (

http://members.ozemail.com.au/~macinnis/scifun/index.htm

) which has won many awards in the past few years. He has been twice awarded âhighly commended' in the Michael Daley Awards for Science Journalism, and in 2000 a children's book he co-authored received a Whitley award from the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.

Peter's work sits at the intersection of three interests: writing, science and education. His next book is about the history and development of rockets. He speaks several languages incredibly badly and has a black belt in bog-snorkelling.

M

any people and institutions helped me in the course of preparing this book. Most of them I found on the Internet, one way or another.

Among the people who helped, I have to count John Gilmore, who discussed James Grainger with me; Michael Sveda, who gave some insights into how his father discovered cyclamates; Alice Holtin in Arkansas, who filled me in on where to learn about southern US sugar cane; Bill Allsopp, also in Arkansas, an amazing educational thinker and fact-fossicker; Lan Wang, who gave me advance files of her scanning of the

Travels of Marco Polo

; and a whole host of people on the Science Matters list: Chris Forbes-Ewan, Margaret Ruwoldt, David Allen, Elizabeth May, Chris Lawson, Gerald Cairns, Tamara, Geoff ZeroSum, Sue Wright, Richard Gillespie and Stephen Berry among them.

Among the helpful institutions, I include the library of Manly Municipality, and its partners in the Shorelink library system, the main and branch libraries of the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales, and also the excellent State Library of New South Wales.

I specifically acknowledge the Australian Government, which taxed all my photocopy charges, the books I bought while researching this, my notebooks and writing paper, my travel, the power that drove my computer, my software, and the shoes I wore out, and then, without having lifted a finger, had the temerity to level a tax on the finished book equal to the amount I get in royalties, and after that will filch half of my royalties as income tax. This service made it very much easier for me to understand the complaints of the sugar growers who had rapacious and parasitic tax-happy regimes to contend with.

At Allen & Unwin, Emma Jurisich, Jo Paul and Ian Bowring patiently prodded me in directions I did not wish to followâat firstâand made this a much better book by their persistence. Then Emma Cotter came on the scene, and showed what happens when a truly erudite editor is let loose on an errant author. When Emma was side-tracked by a brand-new baby, Narelle Segecic took over. It was a seamless transition as Narelle sorted the minor technicalities that arise in any book. I realise now that this editorial flair is the norm at Allen & Unwin. The remaining blemishes result from the recalcitrant author occasionally clinging to one of his

bons mots

contrary to good taste, editorial strictures, public order and the need for good writing.

Thanks also to Chris who has always put up with me, Angus, Cate and especially Duncan, who did some of the library chasing for me, and to Oz Worboys, who introduced me to story of the Kanakas long before I knew of William Wawn, or that he had sailed with my great-grand-uncle (who castigated him for bad language) in the Queensland labour trade. Mike Wright, the demon barber of Balgowlah, swapped philosophies, kept my head cool and prepared me to be photographed. My dentist Thomas Chai undid the damage sugar, and other dentists, had wrought upon my tooth and gave me a place to think.

Finding a name for a book is usually the hardest part. So I asked some friends, sent the best ones as I saw them to Ian Bowring, and then we settled on our best choice. We like it, but lying behind a simple title is a lot of careful thought, from people like Caroline Eising, Bruce Young and Doug Rickard, all in Brisbane, Amanda Credaro in western Sydney, Elizabeth May and Ian Jamie, both from Sydney University, my son Duncan Macinnis and my favourite son-in-law, Julian Ng, Janice Money in Darwin, Cathy Berchtold in Cincinnati, Ohio, Dan Heffron in Fort Myers, Florida, Jeri Bates in Victoria, British Columbia, John Bailey in Somerset, Kathleen Kisting Alam in Lahore and Nancy Baiter in Washington. Thanks, people!

My last-minute checks were ably assisted by the eagle eyes of my son, Angus, and of my good friend Jean Lowerison of San Diego.

I have only myself to blame, but all those people to thank.

A

s far as possible, I have converted measurements and monetary values to a common scale. Most of the masses given are approximations, converted to a notional âton', which is a mix of the metric tonne, the short ton and the avoirdupois ton, which may be divided into 20 hundredweights (cwt). With many of the gallon figures, it is unclear as to whether they should be taken as the modern US gallon (the old English wine gallon of 231 cubic inches) or the modern British gallon (the old English corn gallon of 268.8 cubic inches), or even the beer gallon of 282 cubic inches. âA pint's a pound/the whole world round' say the Americans, even as the British and their Commonwealth once chanted âa pint of pure water/weighs a pound and a quarter'.

Faced with the prospect of boring myself, my editor and my readers witless with voluminous conversions based on often unreliable assumptions about what was meant in the first place, I opted for a retreat into vagueness. I hope this vagueness will be appreciated.

For modern financial measures, I have used an indication of the value in American dollars, since most people seem to be able to translate this into their own currency. Many values, though, were in sterling, and I note here that one pound, three shillings and sixpence is generally written £1 3s. 6d. or as 23s. 6d. There are 20 shillings in a pound, and 12 pence in a shilling. Out of the goodness of my heart, I converted the two instances I encountered of guineas.

A treatise on sugar-refining (the dreariest subject I can think of ) could have been given a more lively appearance.

Joseph Conrad,

Within the Tides

Luckily, the story of sugar is about more than sugar refining. It is a sprawling tale that covers 9000 years, about 150 countries that produce beet or cane sugar, and a product that has influenced all our lives. In telling this story of many threads, the choices I have made from among the many issues help to show how sugar has been involved in world history, although I do not suggest that sugar caused the world to be as it is today. Rather, the human greed, frailty and misjudgment that have in part shaped our world have also operated around the profits to be made, one way and another, from sugar. If sugar had not been available, some other valuable item would have been squabbled over in a similar fashion.

Religion, in a number of guises, has played a part in the story of sugar as well. Sugar probably travelled from Indonesian Hindus to Indian Hindus, and later was made by Nestorian Christians in Persia. After that, sugar followed Islam around the Mediterranean, so it could be discovered by the Crusaders who spread a taste for sugar across Europe. When Catholic nations and Protestant nations competed and warred in the New World and in the east, one of the things they fought over most was sugar.

Later, the wealth to be gained from growing and manufacturing sugar attracted men who sought power, some of whom justified their acts of inhumanity towards other humans, their slaves, in terms of a perverted version of their religion. It is, however, their selective interpretations that we must blame, not religion itself.

The story of sugar has very few heroes and many villains. The villains' consciences remained clear, because they believed that what they did was for the âcommon good', as well as for the good of their pockets. Likewise, those who peddle strange âscientific' claims about sugar and artificial sweeteners today believe that by doing so, they are saving lives. They may be wrong, they may be dishonest, but they seem to believe in their hearts that they are doing good.

Perhaps, before we judge any of sugar's historical figures too harshly, we need to look at ourselves today, and ask how we will be judged by our descendants. It is better to look at the evil men have done, in an effort to ensure that we do not repeat it, than to look upon past evils with a sanctimonious superiority. We are different, but it is doubtful we are that much better, for few things change as little as human nature.