Black Genesis (25 page)

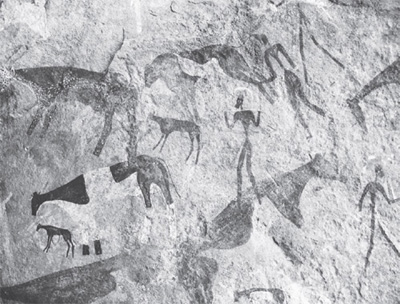

Figure 5.3. Numerous prehistoric hand signatures and, lower left, people depicted as if reflected in a natural crack in the rock. The lower central group is possibly a depiction of a ritual. Mestekawi-Foggini cave, southwest Gilf Kebir.

We woke at the crack of dawn and drove southward until we reached the edge of Uwainat. There, we stopped to visit yet another cave with rock art that was discovered by Mark Borda in 2007. The cave is on the northern edge of Uwainat, and its entrance is tucked behind a ridge, which makes it almost invisible unless you know exactly where to look (which might explain why it was not discovered before 2007). We were, in fact, the first modern visitors to enter this cave since its original inhabitants had abandoned it millennia ago. The cave was half filled with sand up to 1 meter (3 feet) below the ceiling, which actually worked best for us, because most of the rock art was on the ceiling, like a prehistoric Sistine Chapel. The sand allowed us to see the rock art at very close range.

The drawings were of a much better quality than those we saw at Gilf Kebir. Not only were the ancient scenes more elaborate and showed more detail, but the colorsâblacks, browns, reds, yellows, and whitesâwere extremely vivid, as if they had been painted the day before (see plate 14). The cattle were clearly tame and domesticated, and some of them were even shown with halters and leashes or with decorations on their bodies. The men were depicted as tall, slim, and agile. They were black-skinned and wore white ivory bands on their arms and thighs. They also had loincloths resembling those worn later by ancient Egyptians. On some of their heads were ornate hats, and many carried sticks, spears, and bows. The women wore skirts, necklaces, armbands, and earrings. A striking aspect of the renderings of the people was their heads, which were depicted either as wearing masks or symbolically as animal forms (long, rectangular snout, bright eyes, and ears near the top of the head). These animal-form heads, possibly cowlike, might have been representative of the central role that cattle played in the lives of these people. Some of them bore a striking resemblance to the early depictions of the Egyptian god Seth, a god of the desert regions whom the ancient Egyptians associated mythologically with the origin of dynastic Egypt itself. The Sahara scholar and rock art expert Dr. Jean-Loic le Quellec of the French CNRS (Centre National de Recherches Scientifique) is of the opinion that the “cave of swimmers” is a prehistoric precursor and probable influence of rituals found in the much later pharaonic Coffin Texts and Book of the Dead. He thinks the “swimmers” are performing an afterlife journey into the watery afterworld, which he relates to the

mni.w

(the dead who had sunk into the other world) and which confront a mythical Beast, which he related to the ancient Egyptian beasts or monsters,

mmyt,

which swallow the dead in the so-called Judgement Scene of the Book of the Dead. According to Quellec the ancient Egyptians kept the memory of the origins in the Sahara and even may have periodically carried out pilgrimages to revisit their ancestral lands.

Figure 5.4. Bauval and Marai examine newly discovered cave art in April 2008. Note that the back wall of the cave appears to be constructed of megalithic blocks.

The memory of the ancient lands must have lasted for a long time, and was perhaps progressively mythified, following a process that has been well documented in ethnology in many other places in Africa. Perhaps the rituals even demanded a periodic return to ancient cult places . . . like the great shelter of the Wadi Sura. In this way the memory of the ancient vision of the land of the dead, as well as the land of origins, would have been

preserved.

58

The recent finding of Bergmann and Borda fully support this hypothesis, and to which we also agree.

Central to the cave ceiling was a domestic scene, with bags or gourds probably filled with milk or grain, hanging from the roof of a house. There were three types of cows: black and white, all white, and white and brown with black spots. These were drawn in very realistic posturesâwalking, grazing, or being herded to a watering hole. We took photographs from every angle in order to have a detailed record for our own files. Oddly, outside the cave there were no visible signs of human presence as far as we could make out.

*42

Figure 5.5. Cattle and people at Uwainat cave

It is likely that any such evidence lay buried under the sand that had filled the floor of the cave, drifting in and out over the millennia. Our imaginations ran wild: we conjured images of the hardy people who must have lived here thousands of years ago and who, perhaps, hailed originally from the Tibesti Mountains. The rock art they left behind made it easy for us to visualize their women milking cows or grinding seeds and cereals while their men went hunting or chipped stones to make knives and arrow or spear heads and the elderly sat outside at night, pondering the stars. The most thrilling part of this experience was finally to see with our own eyes those mysterious black-skinned ancestors that once navigated the desert, learned the art of husbandry, followed basic agriculture, practiced the rudiments of astronomy and timekeeping, and then finally moved eastward toward the Nile, toward Egypt, carrying their precious cargo: knowledge, which was to spawn a great civilization.

We resumed our journey, skirting the eastern flank of Uwainat Mountain, reaching the Sudanese border early in the afternoon. On our way south we steered clear of a small sign fixed on a metal pole (we examined the sign and saw that it said, in Arabic, misr [Egypt] on one side and sudan on the other, and our handheld GPS indicated it was a few kilometers off the actual border). Continuing south, we drove across the border and around the mountain and found ourselves on the south flank of Uwainat late in the afternoon. Here, the remoteness and utter mystery of this strange place took hold of us. The landscape was otherworldly, and we felt as though we were astronauts landing on an alien planet for the first time. It was very tempting to start exploring, but night was falling fast, so we decided to camp in a sandy bowl set against a rocky mound some 5 kilometers (3 miles) from the mountain.

We hardly slept that night; the excitement was too great. We refrained from lighting a fire in order not to attract SLA rebels that may have been roaming the region. Just a few weeks before, a group of foreign tourists had been kidnapped in this area, and our unarmed military escort was extremely nervous about being here on the Sudanese side of the border. In the morning, at the first break of light, we quickly lifted camp, packed our gear, and set off toward the massif of Uwainat. We headed for the twin peaks that dominated the ridge and toward the place where Marai and Borda had seen the pharaonic inscriptions a few months before. As we drove there, one of the drivers suddenly let out a shout. He had apparently spotted part of a human skeleton sticking out of the sand. We stopped and rushed to examine the shallow burial. It was not prehistoric but was much younger, probably less than a century old. Likely the skeleton belonged to a Tebu nomad or Bedouin. Our drivers could tell he was a Muslim from the way the body was laid. As Muslims themselves, our drivers uttered a brief prayer and covered the exposed part of the skeleton with more sand.

We resumed our drive toward the twin peaks and parked the vehicles at the foot of a rocky slope. Then we all walked in silence, following Marai, still under the somber mood of seeing the lonely burial a few minutes before. After a trek of ten minutes or so, Marai stopped and pointed to a large boulder that rested precariously halfway up the rocky slope. We recognized the boulder from the photographs that Mark Borda had sent us in December. We quickly clambered up the slope, and finally, there they were: pharaonic inscriptions carved on the south face of the boulder.

After Marai and Borda, we were the first modern visitors actually to see them after some unknown ancient Egyptian scribe had crudely carved them thousands of years ago. It was a thrilling and rewarding feelingâperhaps a bit like Howard Carter must have felt when he discovered Tutankhamun's tomb. We knew from the translations that had been made by the Egyptologists in London that the inscriptions dated from about 2000 BCE and likely belonged to an envoy sent by King Mentuhotep II to rendezvous here with people from the kingdoms of Yam and Tekhebet. It was truly exciting to see with our own eyes this extremely ancient message carved thousands of years ago. It was rather like finding a message in a bottle in a vast ocean of sand. We felt privileged and, in a curious way, humbled. We knew the difficulty of such a trip from the Nile Valley, even in our well-equipped, four-wheel-drive vehicles, and we marveled at those unknown ancient Egyptians who had braved the journey on foot with their caravan of donkeys, traveling several months in such conditions.

They must have stayed here for some time, because, lower down the slope, we could see some stone rings that might be the leftover rims of habitations. How many ancient Egyptians had come here? Did the intrepid Harkhuf also come here? Who were the mysterious people from Yam and Tekhebet that they had met here, and from where had they come? Had they come from the Tibesti-Ennedi highlands of Chad some 700 hundred kilometers (435 miles) farther to the southwest? More important: Did the ancient Egyptians know that they were meeting their own ancestors?

Figure 5.6. The April 2008 expedition team anticipating the first showers in eight days upon seeing the tarmac road again. Left to right: Robert Bauval, Dustin Donaldson, Michele Bauval, Mahmoud Marai, Bryan Hokum, Lyra Marble, Thomas Brophy, and soldier Muhammad. Drivers Muhammad and Aziz are taking the photo.

All these questions formed a tantalizing web of hints and clues in our minds, but we knew it was time to return to the Nile Valley to look more closely at the place where Egyptologists say the ancient Egyptian civilization supposedly began.

6

THE CATTLE AND THE STAR GODDESSES

About the time the rains were falling off in the desert, the people in the Nile Valley suddenly started taking an interest in cows, building things with big stones, and getting interested in star worship and solar observatories. . . .

F

RED

W

ENDORF

,

T

HE

N

EW

S

CIENTIST

,

J

ULY

28, 2000

The . . . risings of Sirius had been observed on Elephantine throughout all periods of ancient Egyptian history.

R

ONALD

A. W

ELLS

,

S

OTHIS AND THE

S

ATET

T

EMPLE ON

E

LEPHANTINE

The Egyptians . . . were the first to discover the solar year, and to portion out its course into twelve parts. They obtained this knowledge from the stars.

H

ERODOTUS

,

T

HE

H

ISTORIES

, B

OOK

II

TAMING THE AUROCH

In our modern world we take much for granted. One is the common domestic cowâone of the most gentle, most accommodating, and most useful animals on our planet. When we drive along a country road or walk past an open field and see these gentle and docile animals grazing or lazily walking about, we may give them a fleeting glance, but we soon forget about them. To ancient people, however, cattle were the main display of prosperity. The pharaohs of Egypt, for example, not only measured their wealth by the number of cattle they possessed but also were themselves, as were many of their gods and goddesses, identified with cattle. Yet if cattle were of great importance to the ancient Egyptians, they were of crucial importance to the prehistoric people of the Sahara. Their very survival depended on cattle. Without cattle they simply could not have existed in the harsh conditions in which they lived. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that without cattle there would have been no civilization, at least in the way we understand the word

civilization

today.

When and from where, however, did cattle come, and what did humans do before cattle were domesticated?

Scientists agree that the now extinct auroch, or

Bos primigenius,

is the ancestor of domesticated cattle. The auroch, however, was a much larger and certainly a much more ferocious creature than our common farm cow. Its height was more than 2 meters (7 feet), and it weighed as much as 2 tons. The male auroch was black with faint stripes, and the female was reddish brown. It is probable that the ancestor of the auroch itself existed in Africa some one million years ago and eventually spread to Asia and Europe around two hundred fifty thousand years ago. At first, and for many thousand of years that followed, the auroch was hunted for food by prehistoric manâa feat that must have been quite terrifying and very dangerous indeed, requiring many able hunters who could work together to bring down such a wild and powerful beast. Then, around 8000 BCE, the auroch was finally domesticated, although we don't fully understand where and how. Only a few years ago scientists thought domestication of cattle had originally taken place in Turkey or southwest Asia and that, somewhere along the line, the domesticated breed spread into other parts of the world. Recent research in the mitochondrial DNA of cattle stock from Africa, Asia, and Europe, however, strongly suggests that there was not one domestication event, but several, which occurred independently in each continent in roughly the same epoch.

Normally, domestication of cattle and other animals follows the establishment of agriculture, but there are exceptions. In Africa, for example, domestication took place before agriculture or even without agriculture. The Masai of eastern Africa are well-known herders who do not practice agriculture, yet their lives are completely interwoven with cattle: their protein intakeâmilk, blood, and sometimes meatâis almost totally derived from their cattle. The Masai very rarely kill their cattle for food except on rare occasions, such as important feasts or celebrations. The evidence from Nabta Playa strongly suggests that the prehistoric people there treated their cattle in very much the same way. Furthermore, carbon-14 and other dating methods used by Fred Wendorf indicated that the cattle there were domesticated some ninety-five hundred years ago, making Nabta Playa the earliest known domestication center in the world. In view of this startling conclusion, let us take a closer look at the mysterious cattle people of Nabta Playa, for clearly they were far more sophisticated and resourceful than we previously thought.

BONES AND STONES

We can recall that at Nabta Playa, Fred Wendorf and his team discovered a dozen tumuli on the west side of the site, which contained dismantled bones of cattle and, in one particular case, the complete, articulated skeleton of a young cow. The heads of the cows were all directed south, implying a religious ritual. In addition, when they excavated the largest of the so-called complex structures, CSA was found to contain a huge boulder fashioned in the rough shape of a cow, the so-called cow stone. This stone was removed from its original burial place by anthropologists with a makeshift derrick and was taken to the city of Aswan, where it was placed in the yard of the Nubian Museum.

*43

We also have seen that it was from the cow stone tumuli and CSA that long lines of upright stones emanated like spokes from a bicycle wheel toward the north and the eastâwith the former lines directed toward the Big Dipper and the latter lines toward Sirius and Orion's belt. It should come as no surprise, therefore, to know that much later these three stellar asterisms were also targeted by ancient Egyptians and were even given intense cow and bull symbolism. Indeed, according to most Egyptologists and archaeoastronomers, it is only these three stellar asterisms that can be identified with any certainty from ancient Egyptian texts and

drawings.

1

The pharaohs knew the Big Dipper as Mesekhtyw, the thigh (of a bull or cow), and Sirius as Spdt, which was linked to the well-known cow goddesses Hathor and Isis.

â 44

Orion was known as Sah, and this constellation was associated with Osiris and the pharaoh who, in turn, was also symbolized as a celestial bull and the celebrated Apis Bull of Memphis. Further, all of these clues involving cattle and megalithic astronomy specifically involving Sirius, Orion, and the Big Dipper strongly suggest a link across the centuries of religious ideologies between the prehistoric society of the Sahara and that of pharaonic Egypt. We will return to this and other links between the mysterious cattle/star rituals of Nabta Playa and the various stellar/ cow goddesses and gods of pharaonic Egypt, but first we must understand why the ancients associated their cattle with the rising of

these stars

2

and why this association was so important to the prehistoric black people of Nabta Playa.

NAVIGATING THE SAND SEA

As we saw in chapter 2, when Ahmed Hassanein trekked at night to reach Uwainat, his Tebu guide used the stars to navigate in the featureless desert landscape, very much as some do on the open sea. When we travel in open desert conditions without a compass or GPS, especially at night, it is extremely easy to become confused and lost, with no way of telling direction. In the daytime, traveling is very different: the sun's shadow can be used to establish the cardinal direction at noonâbut at night, and especially on a moonless night, only the stars can perform this role. As an example, we recall that on such a moonless night during our journey, we did not light any fires or lamps at our campsite in order not to advertise our position to SLA rebels or brigands. In such darkness it was nearly impossible for our campsite to be seen beyond a hundred meters (328 feet) or so. The only way to mark its position, therefore, was to use the stars as the Bedouins did. In such open, barren spaces, in fact, it soon becomes second nature to use the stars for navigating at night. Almost certainly the ancient cattle herders of the Sahara did the same. Indeed, these ancient people had all the time in the world to study the night sky, because they were there in the desert, night after night, from generation to generation, from century to century, perhaps even from millennium to millennium. They could become fully familiar with all the observable star cycles, including precession. It is also probable that when they finally became sedentary and settled permanently at Nabta Playa, the need for navigation became obsolete, and thus their practical knowledge of the stars was converted into a star religion with rituals and symbolic structures that, in their minds, allowed them to communicate with the sky gods. The same star religion, but in a much more elaborate form, was later practiced by the ancient Egyptians, or, as we now are beginning to suspect, was inherited from the star cattle people of the Sahara and was further developed.

The immense importance of the stars, especially Sirius, to the ancient Egyptians is recognized by all Egyptologists. Sirius, as is well-known, marked New Year's Day and also served as a cosmic herald of the Nile's annual flood. More important, Sirius was directly associated with the rebirth of kings. Dr. Jaromir Malek, director of the Griffith Institute at Oxford, writes, “The Nile and its annual flooding were dominant factors in the newly formed Egyptian

state”;

3

and Dr. Richard Wilkinson, Egyptologist at the University of Arizona, adds that the great importance of Sirius to the ancient Egyptians “lay in the fact that the star's annual appearance on the eastern horizon at dawn heralded the approximate beginning of the Nile's annual

inundation.”

4

Likewise, Dr. Ian Shaw of Liverpool University and Paul Nicholson of Cardiff University write that “the Egyptian year was considered to begin on . . . the date of the heliacal rising of the Dog Star,

Sirius.”

5

When we observe the daily cycle of Sirius, or indeed of any other star that rises and sets, the place of rising in the east will always be the sameâthat is, it will have the same azimuth.

*45

By placing two or more markers in a straight line aimed at the rising place of a star, such as the upright stones placed at Nabta Playa, an observer can witness that same star rising at that same spot each day. Strictly speaking, however, this is not quite true, for the star has, in fact, moved a bit, but so minute is this movement in one dayâabout 0.00004 of a single degreeâthat it is not possible to notice except with the finest optical instrument. This slight progressive movement is due, as we have seen in previous chapters, to the precession of the equinoxesâthat slow, gyrating motion of Earth, one full cycle of which takes about twenty-six thousand years. Yet although it is not perceptible on a daily or even yearly basis, we can notice it over the span of a human life. For each seventy-two years the change in rising position will be about 1 degreeâthat is, about the thickness of a thumb with the hand outstretched.

â 46

Because the prehistoric star watchers of Nabta Playa observed the rising of stars over several generations and had originally marked their rising points with straight lines of stones, they would surely have become aware that the rising position changed over time. As we have seen in chapter 4, there is even evidence they had a subtle and elegant concept of precessional motion. According to the latest estimates of Wendorf and Schild, Nabta Playa began functioning as a regional ceremonial center during the Middle Neolithic (6100â5500 BCE) and remained in use until about 3500 BCEâthus for at least two millennia of stellar observations. There is also evidence that the site was visited as far back as the early Holocene Period (9000â6100 BCE), thereby giving an even longer observation period. They further explain that “[f]ollowing a major drought which drove earlier groups from the desert, the Late Neolithic began around 5500 BC with new groups that had a complex social system expressed in a degree of organization and control not previously seen. These new people, the Cattle Herders (also known as Ru'at El Baqar people) appear to have been responsible for the ceremonial complex at Nabta Playa. The newcomers had a complex social system that displayed a degree of organization and control not previously seen in

Egypt.”

6

We saw in chapter 4 that the people of Nabta focused their social system that displayed a degree of organization and contol onto creating a megalithic astro-ceremonial complex. One primary feature of that complex was repeated alignments to the rising of Sirius and to the circumpolar Bull's Thigh stars. We might ask, then, why the ancient astronomers of Nabta Playa also marked the rising of the star Sirius. What significance could this have had? In asking this, we are suddenly reminded that this star had its so-called heliacal rising at around the summer solstice, and that it was at this time of year that there began the monsoon rains that filled the lake at Nabta Playa. We can also remember that there was indeed such a summer solstice alignment at Nabta Playa defined by the so-called gate of the calendar circle. Was it possible that these alignments had been intended to work together in order to mark a direction as well as a specific time of year? In other words, could the astronomy of Nabta Playa have served as a point that gave a specific direction at a specific time of year? If so, what did it point to, and at what time of year?

MOVING EAST TOWARD THE NILE VALLEY

Around 6000 BCE, the heavy monsoon rains began to come regularly during the summer solstice season to fill the large depression at Nabta Playa, turning it into a shallow, temporary lake and the region around it into lush prairies that were idyllic for grazing cattle. Further, it was this hydraulic miracle that attracted the so-called Ru'at El Baqar, or cattle people, every monsoon season. Year after year, the cattle people came around the time of the summer solstice to set up camp, graze their cattle on the thick, soft grass along the playa, and remain until the lake eventually dried up some six months later, in midwinter.

In this southern region of the Egyptian Sahara the summer nights are warm and crystal clear, and the starry firmament is a truly marvelous sight to watch. It looms above like a giant cupola or a canopy of twinkling lights that very slowly but perceptibly move majestically from east to west. The constellations appear to be so close that we might be tempted to ignore common sense and reach out to touch them. In these nightly displays, the cattle people had ample time to study the stars, perhaps even name some of the brighter ones and define the more striking of the constellations, such as Orion and the Big Dipper. Surely they passed down their star lore over many generations. Because they were so dependent on their cattle, it was appropriate that they might have noticed that the seven-star asterism of the Big Dipper looked uncannily like the leg of a cow or bull, and that the large constellation of Orion appeared to be a striding giant herdsman holding a staff. Further, it was most likey apt that the heliacal rising of the brightest star of all, Sirius, which hung below Orion's foot, was seen as a sort of beginning or rebirth or, better still, the start of the year to mark the fertility of the coming lifegiving monsoon rains. Certainly these assumptions occurred to Wendorf and his team when they worked at Nabta Playa, for it was reported in

The New Scientist

that

by 1998, Wendorf 's team had found megaliths scattered right across the western edge of the playa. Hoping to fathom what the nomads were up to, Wendorf invited University of Colorado astronomer Kim Malville to Nabta. Malville confirmed that the stones formed a series of stellar alignments, radiating like spokes from the site of the cow sculpture [Complex Structure A]. One of the alignments points to the belt of Orion, a constellation that appears in late spring. Three more indicate the rising points of Dubhe, the brightest star in Ursa Major [Big Dipper], which the Pharaohs saw as the leg of a cow. Most intriguing, though, is the parade of six megaliths marking the rising position of Siriusâthe brightest star in the skyâas it would have appeared 6800 years ago. By that time, says Wendorf, the rains would have started their gradual retreat, and the alignments may have been an attempt to seek help from supernatural forces. To Malville, this seemed an incredible coincidence. Sirius was also of great importance to the civilisations of the Nile, which worshipped it as Sothis. The earliest known Egyptian calendars were calibrated to Sothis's appearance as a morning star, when the days were longest and monsoon rains flooded the crop fields along the Nile. Sothis was depicted as a cow with a young plant between her horns. To later dynasties, Sothis was known as Hathorâmother of the

pharaohs.

7

We have seen that around the fifth millennium BCE the cattle people worked out a way to stay permanently at Nabta Playa by digging deep wells to sustain them through the six months when the lake was dry from midwinter to midsummer. Now they could grow some basic cereal crops and hunt hare and gazelle that also came to the lake when it was full. They rarely, however, slaughtered their own cattle, for these were now considered sacred. They only used them for milk and perhaps blood, very much like the Masai herders of eastern Africa.

*47

With plenty of leisure time on their hands in the evenings and at night, their knowledge of the sky and its cycles increased, and the cattle people thus began to develop complex ideologies of life and death and to devise rituals and ceremonies to mark special days of the year. They gradually built the vast ceremonial complex we see today, using large stones quarried from the nearby bedrock. In the intellectual and spiritual sense, they moved a few steps up the cultural ladder to discard their cattle-people descriptor and become the Ru'at El Asam people, the megalith builders or, as we now prefer to call them, the star people.

Thus life for these people went on peacefully for generations until around 3300 BCE, when huge changes in the climate caused the lake to recede and the wells to dry up. It soon became obvious that they could not stay here much longer. For centuries they had heard of a wonderful river valley in the east, a cornucopia of plenty, with miles upon miles of banks of green pasturesâa place where food and fresh water could be found in abundance. Indeed, their distant ancestors had trade relations with the people of the Nile Valley and even more distant regions. Therefore, forced out by the climate and lured by the legend of the great river, the people of Nabta Playa turned their attention east, toward the place of the rising sun, and dreamed of a new life in the green valley yonder. When they could stay in the desert no more, they rounded up their cattle, packed their meager belongings, and, leaving the ceremonial complex with its stone circle, tumuli, and alignments that their ancestors had raised, they started their march to a new promised land. According to one of the most prominent anthropologists of the Egyptian Sahara, Romuald Schild writes, “And where might they have gone if not to the relatively close Nile Valley? They brought with them the various achievements of their culture and their belief system. Perhaps it was indeed these people who provided the crucial stimulus towards the emergence of state organization in ancient Egypt.” Fred Wendorf echoes these words: “About the time the rains were falling off in the desert, the people in the Nile Valley suddenly started taking an interest in cows, building things with big stones, and getting interested in star worship and solar observatories. Is it possible that the Nabta nomads migrated up the Nile, influencing the great Egyptian

dynasties?”

8

Fekry Hassan, professor of Egyptology at London University, adds: “It is very likely that the concept of the cow goddess in dynastic Egypt is a continuation of a much older tradition of a primordial cow goddess or goddesses that emerged in the context of Neolithic herding in the Egyptian

Sahara.”

9

The modern town of Abu Simbel lies only 100 kilometers (62 miles) due east of Nabta Playaâthree to four days' journey on foot. This would have been the most obvious route to take to reach the Nile Valley. We recall, however, that the central theme of the desert peoples' cosmological beliefs was fixated on the summer solstice sunriseâthe time when both sunrise and the appearance of Orion and Sirius at dawn heralded the monsoon rains that brought life to the desert. Now that the rains came no more, however, did they still look toward the summer solstice for guidance? What propitious sign might the cattle people have taken? The Calendar Circle's summer solstice has an alignment to azimuth of about 62 degreesâthat is, the place of sunrise at summer solstice. Was this a sort of prehistoric pointer for an exodus from Nabta Playa toward the Nile Valley? Was there among the star people of Nabta Playa a prehistoric Moses who led the way toward the rising sun and took his people toward a promised land in the east? At summer solstice the sun remains at more or less the same place for about eight days, with a variation of azimuth as little as 2-arc

minutes.

10

This means that the party of people leaving Nabta Playa had ample time to reach the Nile Valley by walking toward the sunrise. To where might this direction of azimuth 62 degrees have finally led them?