BLACKWATER:The Mysterious Saga of the Caskey Family

Read BLACKWATER:The Mysterious Saga of the Caskey Family Online

Authors: Michael McDowell

BLACKWATER:

The Mysterious Saga of the Caskey Family

Michael McDowell

For Mama El

AVON BOOKS

A division of

The Hearst Corporation

959 Eighth-Avenue

New York, New York 10019

Copyright © 1983 by Michael McDowell Published by arrangement with the author Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 82-90483 ISBN: 0-380-81489-7

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever except as provided by the U. S. Copyright Law. For information address The Otte Company, 9 Goden Street, Belmont, Massachusetts 02178

First Avon Printing, January, 1983

AVON TRADEMARK REG. U. S. PAT. OFF. AND IN OTHER COUNTRIES, MARCA REGISTRADA, HECHO EN U. S. A.

Printed in the U. S. A.

WFH 10 987654321

The maenad loves—and furiously defends herself against love's importunity. She loves— and kills. From the depths of sex, from the dark, primeval past of the battles of the sexes arise this splitting and bifurcating of the female soul, wherein woman first finds the wholeness and primal integrity of her feminine consciousness. So tragedy is born of the female essence's assertion of itself as a dyad. —VYACHESLAV IVANOV, "The Essence of Tragedy" (tr. Laurence Senelick)

I will spunge out the sweetness of my heart, And suck up horror; Love, woman's thoughts,

I'll kill,

And leave their bodies rotting in my mind, Hoping their worms will sting; not man outside,

Yet will I out of hate engender much: I'll be the father of a world of ghosts And get the grave with carcase.

THOMAS LOVELL BEDDOES, "Love's Arrow Poisoned"

AUTHOR'S NOTE

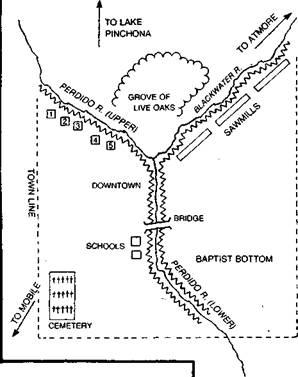

Perdido, Alabama, does indeed exist, and in the place I have put it. Yet it does not now, nor ever did possess the buildings, geography, or population I ascribe to it. The Perdido and Blackwater rivers, moreover, have no junction at all. Yet the landscapes and persons I describe, I venture to say, are not wholly imaginary.

Perdido, Alabama

Perdido, Alabama

pop. 1,200 SITE OF LEVEE WA

1. OSCAR & ELINOR CASKEY'S HOME

2. MARY-LOVE CASKEY'S HOME

3. JAMES CASKEY'S HOME

4. DeBORDENAVES HOME

5. TURK S HOME

TO GULF OF MEXICO

PROLOGUE

At dawn on Easter Sunday morning, 1919, the cloudless sky over Perdido, Alabama, was a pale translucent pink not reflected in the black waters that for the past week had entirely flooded the town. The sun, immense and reddish-orange, had risen just above the pine forest on the far side of what had been Baptist Bottom. This was the low-lying area of Perdido where all the emancipated blacks had huddled in 1865, and where their children and grandchildren huddled still. Now it was only a murky swirl of planks and tree limbs and bloated dead animals. Of downtown Perdido no more was to be seen than the town hall, with its four-faced tower clock, and the second floor of the Osceola Hotel. Only memory might tell where the courses of the Perdido and Blackwater rivers had lain scarcely a week before. All twelve hundred inhabitants of Perdido had fled to higher ground. The town rotted beneath a wide sheet of stinking, still black water, which only now was beginning to recede. The pediments and gables and chimneys of houses that had not been broken up and washed away jutted up through the black shining surface of the flood, stone and brick and wooden emblems of distress. But no assistance came to their silent summonses, and driftwood and unidentifiable detritus and scraps of clothing and household furnishings swept against them and were caught and formed reeking nests around those upraised fingers.

Black water lapped lazily against the brick walls of the town hall and the Osceola Hotel. The water was otherwise silent and unmoving. People who have never lived through a flood may imagine that fish swim in and out of the broken windows of submerged houses, but they don't. In the first place, the windows don't break, for no matter how well constructed a house may have been, the water rises through the floorboards, and the windowless pantry is flooded to the same depth as the front porch. And beyond that, the fish keep to the old riverbeds, just as if they hadn't twenty or thirty feet more of new freedom above that. Floodwater is foul, and filled with foul things, and catfish and bream, though they don't like the unaccustomed darkness, swim in confused circles around their old rocks and their old weeds and their familiar bridge pilings.

Someone standing in the little square room directly beneath the town hall clocks, and peering out the narrow vertical window that looked west, might have seen approaching across that flat black unreflecting surface of still rank water, as out of what remained of the night, a solitary rowboat with two men in it. Yet no one was in that room beneath the clocks, and the dust on the marble floor, and the birds' nests among the rafters, and the gentle whirr of the last bit of machinery that hadn't quite yet run down, remained undisturbed. There was no one to wind the clocks, for who had remained in Perdido when the waters had risen so high? The solitary rowboat plied its stately, solemn course unobserved. It came slowly from the direction of the millowners' fine houses that lay beneath the muddy waters of the Perdido River to the northwest. The boat, which was painted green—for some reason, all such boats in Perdido were painted green—was paddled by a black man about thirty years old. Sitting before him in the prow was a white man, only a few years younger.

Neither had spoken for some time. Each had stared about in wonder at the spectacle of Perdido— where they had been born and where they had been raised—submerged beneath eighteen feet of foul water. What Easter but that first in Jerusalem had dawned so bleakly, or stirred less hope in the breasts of those who had witnessed the rising of that morning's sun?

"Bray," said the white man at last, "row up toward the town hall."

"Mr. Oscar," protested the black man, "we don't know what's in them rooms."

The water had risen to the bottom of the second-floor windows.

"I want to see what's in the rooms, Bray. Go on over."

The black man reluctantly turned the boat in the direction of the town hall, and gave a hard, smooth impetus to the paddle. They sailed close. The boat actually bumped against the marble balustrade of the second-floor balcony.

"You not going in!" cried Bray, when Oscar Gas-key reached out and grasped one of the thick balusters.

Oscar shook his head. The baluster was covered with the slime of the flood. He attempted to wipe it off on his trousers, but succeeded only in transferring some of the stink.

"Nearer that window."

Bray maneuvered the boat to the first window to the right of the balcony.

The sun hadn't got around to that side of the building yet, and the office—that of the town registrar— was dim. The water lay in a shallow black pool over most of the floor. Chairs and tables were scattered about, and a number of file cabinets had been toppled. Others, whose thickly packed contents had become sodden with floodwater, had burst open under the pressure of expansion. Thick rotting sheaves of official county and town documents lay scattered everywhere. A rejected application for voting privileges in the 1872 election lay on the windowsill, and Oscar could even make out the name on it.

"What you see, Mr. Oscar?"

"Not much. I see damage. I see trouble ahead when the water goes down."

"This whole town's gone have trouble when the water go down. So let's don't look in no more windows, Mr. Oscar. Don't know what we gone see."

"What could we see?" Oscar turned around and looked at the black man. Bray had worked for the Caskeys since he was eight years old. He had been hired as a playmate to Oscar, then only four; had graduated into an errand boy, and then to the Gas-keys' principal gardener. His common-law wife, Ivey Sapp, was the Caskey cook.

Bray Sugarwhite continued to paddle the little green boat down the middle of Palafox Street. Oscar Caskey gazed to the right and the left, and attempted to recollect whether the barbershop had a triangular pediment with a carved wooden ball atop it, or whether that ornament belonged to Berta Hamilton's dress shop. The Osceola Hotel loomed up on the right, fifty yards farther on. Its hanging sign had been dislodged sometime on Friday, and probably by this time, was knocking upside of a shrimp boat five miles out in the Gulf of Mexico.

"We not gone look in any more windows, are we, Mr. Oscar?" said Bray apprehensively as they got nearer the hotel. Oscar in the prow was peering this way and that around the sides of that building.

"Bray, I thought I saw something move in one of those windows."

"That the sun," said Bray quickly. "That the sun on them dirty windows."

"It wasn't a reflection," said Oscar Caskey. "You do like I tell you, and you paddle up to that corner window."

"I'm not gone do it."

"Bray, you are gone do it," said Oscar Caskey, not even turning around, "so don't bother telling me you're not. Just go up to that corner window."

"I'm not gone look in no more windows," said Bray, not completely under his breath. Then aloud, as he was changing course and paddling nearer the second floor of the hotel, he said, "Pro'bly rats in there. When the water 'gin to rise in Baptist Bottom, I see the rats come up out of their holes, and they run along the top of the fences. Rats know where it's dry. Ever'body get out of Perdido last Wednesday, it was. So not nothing in that hotel but them smart rats."

The boat bumped against the eastern facade of the brick hotel. The sun reflected a blinding red against the glass panes. Oscar peered through the window nearest him.

All the furniture inside the small hotel room— the bed, the dresser, the chifforobe, the washstand, and the hat rack—were jumbled together in the middle of the floor as if thrown together at the center of a maelstrom that had sunk into the first story. All of it was covered with mud. The carpet, muddy and stiff and black, was bunched together in the corner against the door. In the dimness Oscar could not make out the high-water mark on the dark wallpaper.

The carpet trembled, and Oscar saw two large rats rush from a fold of the rug toward the hill of furniture in the center of the room. Oscar jerked his gaze from the window.

"Rats?" asked Bray. "See! I tell you, Mr. Oscar, nothing in this hotel but rats. Don't need to be looking through no more windows."

Oscar Caskey didn't answer Bray, but he stood up, and, grasping the frame of the tattered awning of the next window, he pulled the boat toward the corner of the hotel.

"Bray," said Oscar Caskey, "this is the window where I saw something move. I saw something pass in front of this window, and it wasn't any rat 'cause rats aren't five feet high."

"Rats been feeding on the flood," said Bray, though what he meant to suggest Oscar wasn't certain.

Oscar leaned forward in the boat, grasping the concrete casement of the window with both hands. He peered through the dirty panes.

The corner room appeared to have been untouched by the floodwaters. The bed, quietly made, stood where it ought, against the long corridor wall, and the rug was squarely arranged beneath it. The chif-forobe and the dresser and the washstand were in their places. Nothing had fallen to the floor and broken. However, where the sun, shining through the eastern window, illuminated a large patch of the carpet, Oscar saw that it was sopping wet—so that he was forced to conclude that the water had risen through the floorboards.

But why the furniture in this room should have remained so placidly in place while everything in the adjoining chamber had been broken apart and tossed together and—as a last indignity—sheeted in black mud, Oscar could not puzzle out.