Blockade Billy (3 page)

Authors: Stephen King

Tags: #King; Stephen - Prose & Criticism, #Horror, #General, #Fiction - General, #Suspense, #Horror - General, #Fiction, #Sports

Ah, that’s good. Been a long time since I talked so much, and I got a lot more to say. You bored yet? No? Good. Me neither. Having the time of my life, awful story or not.

Anderson didn’t play again until ’58, and ’58 was his last year—Boston gave him his unconditional release halfway through the season, and he couldn’t catch on with anyone else. Because his speed was gone, and speed was really all he had to sell. The docs said he’d be good as new, the Achilles tendon was only nicked, not cut all the way through, but it was also stretched, and I imagine that’s what finished him. Baseball’s a tender game, you know; people don’t realize. And it isn’t only catchers who get hurt in collisions at the plate.

After the game, Danny Doo grabs the kid in the shower and yells: “I’m gonna buy you a drink tonight, rook! In fact, I’m gonna buy you

ten!”

And then he gives his highest praise:

“You hung the fuck in there!”

“Ten drinks, because I hung the fuck in there,” the kid says, and The Doo laughs and claps him on the back like it’s the funniest thing he ever heard.

But then Pinky Higgins comes storming in. He was managing the Red Sox that year, which was a thankless job; things only got worse for Pinky and the Sox as the summer of ’57 crawled along. He was mad as hell, chewing a wad of tobacco so hard and fast the juice squirted from both sides of his mouth and ran down his chin. He said the kid had deliberately cut Anderson’s ankle when they collided at the plate. Said Blakely must have done it with his fingernails, and the kid should be put out of the game for it. This was pretty rich, coming from a man whose motto was, “Spikes high and let em die!”

I was sitting in Joe’s office drinking a beer, so the two of us listened to Pinky’s rant together. I thought the guy was nuts, and I could see from Joe’s face that I wasn’t alone.

Joe waited until Pinky ran down, then said: “I wasn’t watching Anderson’s foot. I was watching to see if Blakely made the tag and held onto the ball. Which he did.”

“Get him in here,” Pinky fumes. “I want to say it to his face.”

“Be reasonable, Pink,” Joe says. “Would I be in your office doing a tantrum if it had been Blakely all cut up?”

“It wasn’t spikes!” Pinky yells. “Spikes are a part of the game! Scratching someone up like a…a girl at a

kickball match

…that

ain’t!

And Anderson’s in the game seven years! He’s got a family to support!”

“So you’re saying what? My catcher ripped your pinch-runner’s ankle open while he was tagging him out—and tossing him over his goddam shoulder, don’t forget—and he did it with his

nails?”

“That’s what Anderson says,” Pinky tells him. “Anderson says he felt it.”

“Maybe Blakely stretched Anderson’s foot with his nails, too. Is that it?”

“No,” Pinky admits. His face was all red by then, and not just from being mad. He knew how it sounded. “He says that happened when he came down.”

“Begging the court’s pardon,” I says, “but

fingernails?

This is a load of crap.”

“I want to see the kid’s hands,” Pinky says. “You show me or I’ll lodge a goddam protest.”

I thought Joe would tell Pinky to shit in his hat, but he didn’t. He turned to me. “Tell the kid to come in here. Tell him he’s gonna show Mr. Higgins his nails, just like he did to his first-grade teacher after the Pledge of Allegiance.”

I got the kid. He came willingly enough, although he was just wearing a towel, and didn’t hold back showing his nails. They were short, clean, not broken, not even bent. There were no blood-blisters, either, like there might be if you really set them in someone and raked with them. One little thing I did happen to notice, although I didn’t think anything of it at the time: the Band-Aid was gone from his second finger, and I didn’t see any sign of a healing cut where it had been, just clean skin, pink from the shower.

“Satisfied?” Joe asked Pinky. “Or would you like to check his ears for potato-dirt while you’re at it?”

“Fuck you,” Pinky says. He got up, stamped over to the door, spat his cud into the wastepaper basket there—

splut!

—and then he turns back. “My boy says

your

boy cut him. Says he felt it. And my boy don’t lie.”

“Your boy tried to be a hero with the game on the line instead of stopping at third and giving Piersall a chance. He’d tell you the moon was made of his father’s come-stained skivvies if it’d get him off the hook for that. You know what happened and so do I. Anderson got tangled in his own spikes and did it to himself when he went whoopsy-daisy. Now get out of here.”

“There’ll be a payback for this, DiPunno.”

“Yeah? Well it’s the same gametime tomorrow. Get here early.”

Pinky left, already tearing off a fresh piece of chew. Joe drummed his fingers beside his ashtray, then asked the kid: “Now that it’s just us chickens, did you do anything to Anderson? Tell me the truth.”

“No.” Not a bit of hesitation. “I didn’t do anything to Anderson. That’s the truth.”

“Okay,” Joe said, and stood up. “Always nice to shoot the shit after a game, but I think I’ll go on home and have a drink. Then I might fuck my wife on the sofa. Winning on Opening Day always makes my pecker stand up.” Then he said, “Kid, you played the game the way it’s supposed to be played. Good for you.”

He left. The kid cinched his towel around his waist and started back to the locker room. I said, “I see that shaving cut’s all better.”

He stopped dead in the doorway, and although his back was to me, I knew he’d done something out there. The truth was in the way he was standing. I don’t know how to explain it better, but…I knew.

“What?” Like he didn’t get me, you know.

“The shaving cut on your finger.”

“Oh,

that

shaving cut. Yuh, all better.”

And out he sails…although, rube that he was, he probably didn’t have a clue

where

he was going. Luckily for him, Kerwin McCaslin had got him a place to stay in the better part of Newark. Hard to believe as it might be, Newark had a better part back then.

Okay, second game of the season. Dandy Dave Sisler on the mound for Boston, and our new catcher is hardly settled into the batter’s box before Sisler chucks a fastball at his head. Would have knocked his fucking eyes out if it had connected, but he snaps his head back—didn’t duck or nothing—and then just cocks his bat again, looking at Sisler as if to say,

Go on, mac, do it again if you want

.

The crowd’s screaming like mad and chanting

RUN IM! RUN IM! RUN IM!

The ump didn’t run Sisler, but he got warned and a cheer went up. I looked over and saw Pinky in the Boston dugout, walking back and forth with his arms folded so tight he looked like he was trying to keep from exploding.

Sisler walks twice around the mound, soaking up the fan-love—boy oh boy, they wanted him drawn and quartered—and then he went to the rosin bag, and then he shook off two or three signs. Taking his time, you know, letting it sink in. The kid all the time just standing there with his bat cocked, comfortable as old Tillie. So Dandy Dave throws a get-me-over fastball right down Broadway and the kid loses it in the left field bleachers. Tidings was on base and we’re up two to nothing. I bet the people over in New York heard the noise from Swampy when the kid hit that home run.

I thought he’d be grinning when he came around third, but he looked just as serious as a judge. Under his breath he’s muttering, “Got it done, Billy, showed that busher and got it done.”

The Doo was the first one to grab him in the dugout and danced him right into the bat-rack. Helped him pick up the spilled lumber, too, which was nothing like Danny Dusen, who usually thought he was above such things.

After beating Boston twice and pissing off Pinky Higgins, we went down to Washington and won three straight. The kid hit safe in all three, including his second home run, but Griffith Stadium was a depressing place to play, brother; you could have gunned down a running rat in the box seats behind home plate and not had to worry about hitting any fans. Goddam Senators finished over forty games back that year. Forty! Jesus fucking wept.

The kid was behind the plate for The Doo’s second start down there and damn near caught a no-hitter in his fifth game wearing a big league uniform. Pete Runnels spoiled it in the ninth—hit a double with one out. After that, the kid went out to the mound, and that time Danny didn’t wave him back. They discussed it a little bit, and then The Doo gave an intentional pass to the next batter, Lou Berberet (see how it all comes back?). That brought up Bob Usher, and he hit into a double play just as sweet as you could ever want: ballgame.

That night The Doo and the kid went out to celebrate Dusen’s one hundred and ninety-eighth win. When I saw our newest chick the next day, he was very badly hungover, but he bore that as calmly as he bore having Dave Sisler chuck at his head. I was starting to think we had a real big leaguer on our hands, and wouldn’t be needing Hubie Rattner after all. Or anybody else.

“You and Danny are getting pretty tight, I guess,” I says.

“Tight,” he agrees, rubbing his temples. “Me and The Doo are tight. He says Billy’s his good luck charm.”

“Does he, now?”

“Yuh. He says if we stick together, he’ll win twenty-five and they’ll have to give him the Cy Young.”

“That right?”

“Yessir, that’s right. Granny?”

“What?”

He was giving me that wide blue stare of his: twenty-twenty vision that saw everything and understood practically nothing. By then I knew he could hardly read, and the only movie he’d ever seen was

Bambi

. He said he went with the other kids from Ottershow or Outershow—whatever—and I assumed it was his school. I was both right and wrong about that, but it ain’t really the point. The point is that he knew how to play baseball—instinctively, I’d say—but otherwise he was a blackboard with nothing written on it.

“What’s a Cy Young?”

That’s how he was, you see.

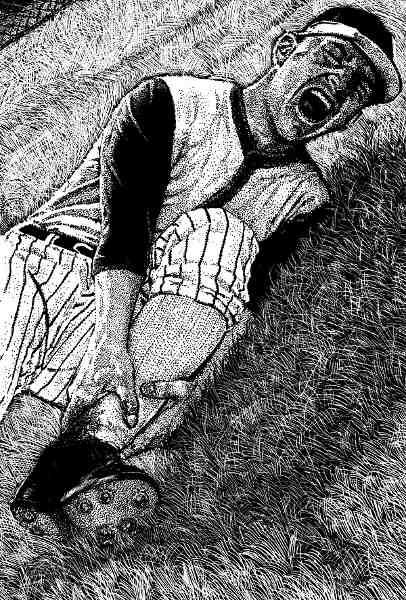

We went over to Baltimore for three before going back home. Typical spring baseball in that town, which isn’t quite south or north; cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey the first day, hotter than hell the second, a fine drizzle like liquid ice the third. Didn’t matter to the kid; he hit in all three games, making it eight straight. Also, he stopped another runner at the plate. We lost the game, but it was a hell of a stop. Gus Triandos was the victim, I think. He ran headfirst into the kid’s knees and just lay there stunned, three feet from home. The kid put the tag on the back of his neck just as gentle as Mommy patting oil on Baby Dear’s sunburn.

There was a picture of that put-out in the Newark

Evening News

, with a caption reading

Blockade Billy Blakely Saves Another Run

. It was a good nickname and caught on with the fans. They weren’t as demonstrative in those days—nobody would have come to Yankee Stadium in ’57 wearing a chef’s hat to support Gary Sheffield, I don’t think—but when we played our first game back at Old Swampy, some of the fans came in carrying orange road-signs reading DETOUR and ROAD CLOSED.

The signs might have been a one-day thing if two Indians hadn’t got thrown out at the plate in our first game back. That was a game Danny Dusen pitched, incidentally. Both of those put-outs were the result of great throws rather than great blocks, but the rook got the credit, anyway, and I’d say he deserved it. The guys were starting to trust him, see? And they wanted to watch him do it. Baseball players are fans, too, and when someone’s on a roll, even the most hard-hearted try to help.

Dusen got his hundred and ninety-ninth that day. Oh, and the kid went three for four, including a home run, so it shouldn’t surprise you that even more people showed up with those signs for our second game against Cleveland.

By the third one, some enterprising fellow was selling them out on Titan Esplanade, big orange cardboard diamonds with black letters: ROAD CLOSED BY ORDER OF BLOCKADE BILLY. Some of the fans’d hold em up when Blockade Billy was at bat, and they’d all hold them up when the other team had a runner on third. By the time the Yankees came to town—this was going on to the end of April—the whole stadium would flush orange when the Bombers had a runner on third, which they did often in that series.

Because the Yankees kicked the living shit out of us and took over first place. It was no fault of the kid’s; he hit in every game and tagged out Bill Skowron between home and third when the lug got caught in a rundown. Skowron was a moose the size of Big Klew, and he tried to flatten the kid, but it was Skowron who went on his ass, the kid straddling him with a knee on either side. The photo of that one in the paper made it look like the end of a Big Time Wrestling match with Pretty Tony Baba for once finishing off Gorgeous George instead of the other way around. The crowd outdid themselves waving those ROAD CLOSED signs around. It didn’t seem to matter that the Titans had lost; the fans went home happy because they’d seen our skinny catcher knock Mighty Moose Skowron on his ass.

I seen the kid afterward, sitting naked on the bench outside the showers. He had a big bruise coming on the side of his chest, but he didn’t seem to mind it at all. He was no crybaby. The sonofabitch was too dumb to feel pain, some people said later; too dumb and crazy. But I’ve known plenty of dumb players in my time, and being dumb never stopped them from bitching over their booboos.