Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America (26 page)

Read Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America Online

Authors: Patrick Phillips

Tags: #NC, #United States, #LA, #KY, #Social Science, #SC, #MS, #VA, #20th Century, #South (AL, #TN, #History, #FL, #GA, #WV), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #State & Local, #AR

There is no way to know exactly where the black Strickland, Moon, and Rocks families went during the first waves of violence, but there is strong evidence that they fled along with the rest of the African American community. When Ed Moon filled out a WWI draft card in 1918, he was living forty miles east of Cumming, in Maysville, a town the white Stricklands had helped found in Jackson County in the nineteenth century. Jackson happened to be the birthplace of Forsyth’s largest slave owners—Hardy, Tolbert, and Oliver Strickland—and was still home to many of their kin. One likely scenario is that when the mobs of Forsyth threatened black employees like Ed Moon, the white Stricklands simply relocated them to other family farms in Jackson County. And then, at some point after the violence had died down, and prior to the 1920 census, the Stricklands quietly brought some of their black laborers back into Forsyth, where they were isolated but protected as long as they stayed on Strickland property.

Whether it was the lure of wages, the threat of punishment, or a lack of any better option, at some point after 1918, at great risk, those twenty-three people stepped back across the invisible line and were counted as Forsyth residents in 1920. No mention was made in the papers, no mobs assembled at the edge of the Strickland place, and there is no record of their presence other than those few entries that Vester Buice scrawled in his census ledger.

As enraged as locals had been at the sight of the “Seeing Georgia” chauffeurs, they likely knew better than to test the rich and powerful white Strickland clan. That small cluster of black people at the southern edge of the county still numbered sixteen in the census of 1930. Then, at some point after 1930, they were gone. The Moons to Gainesville. Will and Corrie Strickland just nine miles south, to Milton County, near Alpharetta, and Marvin and Rubie Rocks to some new life of which no traces survived.

ACROSS THE CHATTAHOOCHEE

, in Hall County, Jane Daniel was just starting to imagine a more ambitious escape—not just from the lynchers and night riders of Forsyth but out of the South altogether. In the census of 1920, we can still find her, age twenty-nine, pinning white people’s damp clothes to the line in her backyard, as somewhere in Gainesville Will Butler gripped the wooden handle of a pair of steel pincers and lugged a fifty-pound block of ice through the back door of a white man’s mansion. But when the census taker came back to Atlanta Street in 1930, neighbors said that Will and Jane were gone—having boarded a northbound train at the depot in Gainesville and joined so many other young black people of their generation in the Great Migration.

By the early 1930s, Jane Daniel and Will Butler were renting a house at 467 Theodore Street, in the Paradise Valley neighborhood of Detroit. Having grown up in rural Forsyth and then lived in the small railroad city of Gainesville, Jane suddenly found herself at the center of a booming industrial metropolis. Census records show that Jane and Will’s neighborhood was filled with others who had been born to sharecroppers and field hands in Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Virginia, and Mississippi—but who now worked as cooks, maids, bricklayers, and night watchmen.

And more than anywhere else, the black residents of Detroit worked in the bustling factories of Motor City: Fisher Body, at

the corner of Piquette and St. Antoine; Cadillac’s Detroit Assembly, on Clark Street; and the Hudson Motors plant, off Jefferson Avenue. Whereas the backdrop of her youth had been pine forests, cotton fields, and the lazy, deep green waters of the Chattahoochee, the second half of Jane’s life would play out amidst smokestacks and glowing steel ingots, in a city whose pulse in its heyday one visitor described as “the sound of a hammer against a steel plate.”

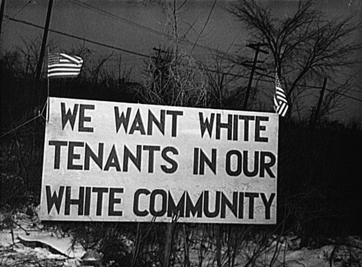

Sign protesting the arrival of black tenants, Sojourner Truth housing project, Detroit, February 1942

One migrant of Jane’s generation described the life she left behind in the Jim Crow South as “like sleeping on a volcano which may erupt at any moment,” and Jane must have felt a similar kind of relief once she and Will were settled in Detroit—to be out of Georgia, and beyond the reach of the white people who had killed her first husband, Rob, and celebrated the hanging of her brother Oscar and her cousin Ernest. Will and Jane never had children, but the nieces and nephews who knew them in Detroit all understood that Aunt Janie and Uncle Will had begun their lives far away, among

the crackers and Klansmen down in Georgia. “

Georgia

,” they said years later, “was not a place Aunt Janie ever talked too much about.”

BUT IF THE

Butlers thought they had escaped white terrorism, they and the rest of Detroit got a rude awakening in the summer of 1943, when the white people of the city decided that they, too, would declare a racially cleansed zone and draw an invisible line that blacks could cross only at risk of their lives.

Racial tensions had been building since the first trainloads of migrants began arriving from the South after World War I. The African American population of the city was just 6,000 in 1910, but by 1929 some 120,000 new black residents had settled in Detroit, and a decade later, in 1940, that number had nearly doubled, to 200,000. During that same span of years, European immigrants were also arriving in unprecedented numbers, and for many of the same reasons: the magnetic draw of high wages and low unemployment, and a chance to escape the violence and deprivation they’d suffered in their homelands.

By the early 1940s, there were simmering tensions between whites and blacks in the city, and they boiled over in the winter of 1942. That was the year the federal government opened the new Sojourner Truth housing project, which was built especially for poor black families but located in a predominantly white area north of Paradise Valley. When the first tenants arrived, on February 28th, neighborhood whites burned a cross in a field near the housing complex, and the next morning a mob of twelve hundred armed white men rallied to keep out black residents—many of whom had already signed leases and paid their first month’s rent. Whites formed a picket line in front of the building, and when two cars driven by black men tried to force their way through the line, a melee broke out. The violence ended only when mounted police arrived with shotguns and tear gas.

White mob dragging an African American man from a Detroit streetcar, June 21, 1943

In April of 1942, 168 black families finally moved into the housing complex, under the protection of the Detroit Police Department and sixteen hundred troops of the Michigan National Guard. Like Jane and Will Butler, the great majority of those families had migrated to Detroit from the South. As they went to bed on their first night in Sojourner Truth—with the racist taunts of whites rising up past the windows of the new high-rise—many must have wondered if they had simply traded one band of night riders for another.

The chaos at Sojourner Truth was only a prelude to what Jane and Will experienced the following summer, when twenty-five thousand

workers at Packard walked off the assembly line because black employees had been promoted to jobs that placed them shoulder to shoulder with whites. As one enraged man said outside the plant, “I’d rather see Hitler and Hirohito win than work beside a nigger.”

The shoving and shouting outside Packard turned to more serious violence on the night of June 20th, 1943, when two young black men were expelled from Belle Isle Park, in the middle of the Detroit River. On the bridge linking the park to the city, a skirmish broke out between groups of blacks and whites. In the wake of the clash, a rumor quickly spread across the city: that “blacks had raped and murdered a white woman on the Belle Isle Bridge.”

Many people surely recognized this as the “old threadbare lie” that had fueled half a century of lynch law in the South. But once infuriated whites believed that a gang of black men had “violated” and killed a white woman and thrown her body into the river, it hardly mattered that the story was untrue. If Jane dared to venture out into the city during the three days that followed, she would have witnessed a familiar scene: black bodies being dragged through the streets by gangs of white men.

Witnesses told of mobs ambushing and beating black passengers as they stepped down off trolley cars; a fifty-eight-year-old black man named Moses Kiska being shot and killed for waiting at a bus stop in the wrong part of town; and an unnamed black man being bludgeoned on Woodward Avenue as four white police officers looked on. Jane and Will’s house was just two blocks from Woodward, in the middle of what quickly became a war zone. By the time military troops arrived to stop the rampage, there were thirty-four confirmed killings. Most of the victims had been beaten to death with wooden clubs.

Langston Hughes wrote that at least in the North he had his own “window to shoot from,” and in June of 1943, in Detroit, that’s exactly what black residents like Jane and Will Butler did: keep

watch with loaded rifles, stiff-jawed as they waited for the roving mobs. Many of the attackers had European instead of southern accents, but their faces were contorted with the same hatred Jane had seen so many times in Forsyth. All she could do, as so often in her life, was hope that the future might be different. As it said on the flags flying over Detroit’s city hall,

Speramus meliora:

“We hope for better things.”

DURING THE SAME

decades that Jane and Will struggled to build a new life in the North, Forsyth was deep in its sleep of forgetfulness, as all around it the state of Georgia veered even further in the direction of white supremacy. The 1933 governor’s race was won by Eugene Talmadge, a south Georgia farmer who proudly grazed a cow on the lawn of the governor’s mansion and courted the votes of poor rural whites by casting himself as the last line of defense against a “Nigra takeover.” Talmadge held the governorship for three terms between 1933 and 1943 and was, according to writer Gilbert King, “a racial demagogue who presided over a Klan-ridden regime.” In a typical campaign speech in 1942, Talmadge answered a question about school integration by reassuring his segregationist base: “Before God, friend, the niggers will never go to a school which is white while I am Governor.”

One of the few glimpses from inside Forsyth during this period comes from a white woman named Helen Matthews Lewis, who moved into the county as a ten-year-old in 1934, when her father was hired as a county mail carrier. Lewis remembered a white community still very much in the grips of its original paranoia and still openly proud of having “run the niggers out” in 1912. “I was told stories [as a child],” Lewis said,

about how they hung blacks around the courthouse. I knew they lynched the guy that they were accusing of [the rape of Mae Crow]. Stories were told. I could just see bodies hanging all around the courthouse in my mind.

Lewis sometimes caught sight of frightened black deliverymen passing through the county in 1930s: “[Back] then blacks coming in through town on trucks to deliver stuff to the stores were afraid to get out. . . . They would hide in the back.” Lewis also remembered that many Forsyth residents were quick to react to even the slightest trespass across the racial border—from the appearance of a black worker on the back of a truck to an old man who strayed into Forsyth while riding a bicycle north toward Hall County. “My father came home from his mail route one day,” Lewis said,

and he said he saw this old black man bicycling through town on his way to Gainesville. My father said “I’m worried he’s got to go through Chestatee” . . . [past] the rowdy boys of Chestatee. [My father] said “He’ll never make it,” so he gets in his car and he said “I’m going to go find him,” then he goes and picks him up and takes him to Gainesville.

Lewis remembered how another outsider violated the unwritten code in the late 1930s—a woman who moved to the county with her long-serving black maid. “When I was in school” at Forsyth County High, Lewis said,

this teacher comes to town . . . who had this black woman who was a companion, maid, a person who’d always been in their family. And she taught music and the woman lived with her [until] these boys . . . came with torches and surrounded her house and made her get up in the middle of the night and take the black woman back to Alabama.