Blood Brotherhoods (115 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

In September 2012 the

Insuperabile

crew had their obelisk confiscated and destroyed because, according to the judge who authorised the confiscation,

The messages it sends, the hidden meaning of that wood and papier mâché, is worth more than a whole arsenal to the clan. Deploying it on the day of the festival means much more than a victory in battle, than the physical annihilation of a rival: it is a sign of authority.

Using community religious celebrations as a chance to parade criminal might is traditional in the Naples underworld. In the nineteenth century,

camorristi

used to take control of the springtime pilgrimage to the sanctuary of Montevergine. Each boss, with his woman next to him decked out in silk, gold and pearls, would drive his pony and trap into the mountains at the head of his followers. The pilgrims’ progress would be punctuated by drinking bouts, races, more or less stylised knife fights, and camorra summits with the clans of the hinterland.

Similar things characterised mafia life in Calabria and Sicily. In towns and villages controlled by the ’ndrangheta and Cosa Nostra, criminal territorial control was advertised by taking over the day set aside to celebrate the local patron saint. Barra is far from being the only place where the tradition continues to this day. In Sant’Onofrio in 2010, the ’ndrangheta reacted angrily when the local priest tried to enforce the Bishop’s order to ban mobsters from taking a leading role in an Easter parade of statues of the Madonna: the head of the confraternity that presided over the festival received a warning when two shots were fired at his front door. The festival was suspended for a week, and when it eventually took place, the

Carabinieri

were out in force.

So has nothing changed in Campania? Is the camorra still the force it once was? Certainly, a ‘murder map’ of underworld deaths over the last few decades would have its dots concentrated in the same broad area that has been blighted by the camorra since the nineteenth century: the city of Naples and a semicircle of roughly forty-kilometre radius extending out into the towns and villages of the hinterland. An enduring pattern is unmistakable. Yet once we zoom in on the detail of our map of camorra power, it becomes clear that the continuities are less prevalent than they first appeared. Less prevalent, certainly, than in Sicily and Calabria, where the micro-territories demarcated by mafia

cosche

have remained all but

identical. Places like Rosarno and Platì (’ndrangheta), or Villabate and Uditore (Cosa Nostra) have been notorious for well over a century. In Campania, by contrast, the geography of the underworld has seen some important transformations recently.

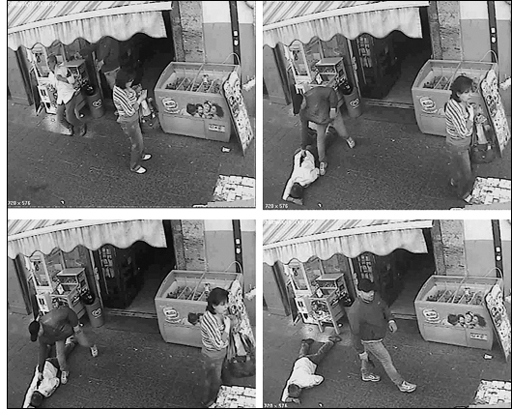

CCTV footage shows a camorra killer calmly finishing off his victim, Naples, 2009.

The camorra fragmented following the war in the early 1980s between Raffaele ‘the Professor’ Cutolo and the allied clans of the Nuova Famiglia. There were an estimated thirty-two camorra organisations in 1988; that number had increased to 108 by 1992. The years of the Second Republic have seen no reversal of the fragmentation. The most recent estimates suggest that there are still around a hundred sizeable criminal organisations in Campania, where gangland has assumed a lasting but instable pattern. Camorra clans come and go, merge and break apart, go to war and make alliances. Thus most of these camorras have a very short lifespan compared to the extraordinarily persistent criminal Freemasonries, Cosa Nostra and the ’ndrangheta. In Campania, the lines on the map of camorra power move constantly as the police make arrests, turf wars break out and clans fissure and merge. Increased violence is the inevitable consequence of this fundamental instability: the camorra continues to kill more people than either the

Sicilian mafia or the ’ndrangheta. There have been several major peaks in the murder rate in recent years: there were over a hundred camorra killings each year from 1994 to 1998; and then again in 2004, and again in 2007.

Naples is a port city. That simple fact has shaped the camorra’s history ever since the 1850s and 1860s, when Salvatore De Crescenzo’s camorra smuggled imported clothes past customs and extorted money from the boatmen ferrying passengers from ship to shore. The port of Naples was where vast quantities of Allied materiel vanished onto the black market during the Second World War. In the 1950s, the travelling cloth-salesmen known as

magliari

, who were often little more than swindlers, would set sail to bring the sharp practices of the Neapolitan rag trade to the housewives of northern Europe. Thereafter, Naples was a point of entry for contraband cigarettes and narcotics. These days, the port is a mechanised container terminal on the model of Rotterdam or Port Elizabeth, NJ. It has assumed new importance as a gateway to Italy for the Far Eastern manufactures that are shipped into the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. Some of those manufactures—shoes, clothes and handbags, electrical tools, mobile phones, cameras and games consoles—are forged versions of market-leading brands. The Neapolitan tradition of manufacturing counterfeits has gone global. Sometimes, the label ‘Made in Italy’ or ‘Made in Germany’ hides a different reality: ‘Faked in China’. And in place of the

magliari

, there are international brokers, permanently stationed abroad to find markets for bootleg products. Quite how large this sector is, and quite what proportions of it are run by

camorristi

as opposed to garden-variety shady entrepreneurs, is still subject to investigation.

Naples is a remarkable place for many reasons. One of them is the fact that, where historic poor neighbourhoods in many other European cities have long ago been demolished or yuppified, the centre of Naples still has many of the same concentrations of poverty that characterised it back in the eighteenth century. Forcella, the ‘kasbah’ quarter we have visited occasionally through this story, is a case in point. The camorra rose from its fetid and overcrowded alleys in the early nineteenth century. Although much is now different in Forcella, not least the sanitation, eking out a living here is still precarious, often illegal, and occasionally dangerous. No visitor can enter without the distinct sensation of being watched. In this and other neighbourhoods, the camorra’s territorial purview is still made manifest by the kids who extort money for parking places, and the cocksure teenagers perched atop their scooters who act as lookouts for drug dealers.

Despite the wholesale economic transformation of the last century and a half, in places like Forcella the camorra continues to recruit among a population made vulnerable by hardship and a widespread disregard for the law, just as it did in the nineteenth century. In 2006, it was estimated that 22 per cent of people with any kind of job in Campania worked in the so-called ‘black economy’—paid in cash, untaxed and unprotected by labour and safety laws. It seems likely that a sizeable majority of jobs in small- and medium-sized companies are off the books.

Recent economic change seems to have made the situation worse. In Campania, as in much of the South, the new economic mantra of flexible employment has often meant just a bigger black economy. Since 2008, Europe’s dire economic difficulties have increased the power of the camorra (and, for that matter, of Cosa Nostra and the ’ndrangheta) to penetrate businesses, and lock the region into a vicious circle of economic failure. In the summer of 2009, Mario Draghi, then the president of the Bank of Italy, argued as follows:

Companies are seeing their cash flow dry up, and their assets fall in market value. Both of these developments make them easier for organised crime to attack . . . In economies where there is a strong criminal presence businesses pay higher borrowing costs, and the pollution of local politics makes for a ruinous destruction of social capital: young people emigrate more, and nearly a third of those young people are graduates moving north in search of better opportunities.

In hard times, it is not just fly-by-night businesses that are easy prey for loan sharks and extortionists, for gangsters seeking an outlet for stolen goods or a way to launder drug profits. By the nature of the narcotics business, gangsters are cash rich—and just at the moment southern Italy’s entrepreneurs are struggling even more than everyone else to get their hands on credit. When times are hard, cash is

capo

.

The camorra’s undiminished power to feed off the weaknesses of the Neapolitan economy has helped remould the landscape of criminal influence. Once upon a time, when Naples was an industrial city, factory workers had a tradition of labour organisation and socialist ideals that gave them an inbuilt resistance to the camorra infection. Nowadays, with the factories largely gone, the camorra has spread to quarters like Bagnoli, where the steelworks shut down in the 1990s.

Today, moreover, the urban camorra economy no longer revolves around the old slums of the city centre. The major concentrations of poverty and illegality have moved away from the Naples that tourists know. Even the

camorra in Forcella has felt the force of the new. The Giuliano clan (centred on ‘Ice Eyes’ and his brothers) has been broken by murder, repentance and arrest. More importantly, the most powerful and dangerous clans now emerge from the sprawling periphery of the city, from neighbourhoods that grew anarchically in the 1970s and after the earthquake of 1980. The artisan studios of the city-centre maze cannot compete with the sweatshop factories of the suburbs when it comes to churning out bootleg DVDs and counterfeit branded fashions. With the modernisation of Naples’s road network and public transport, addicts now find it cheaper to source their hit from the great narcotics supermarkets operating in the brutalist apartment blocks of Secondigliano or Ponticelli, than to visit the small-time dealers of the Spanish Quarters.

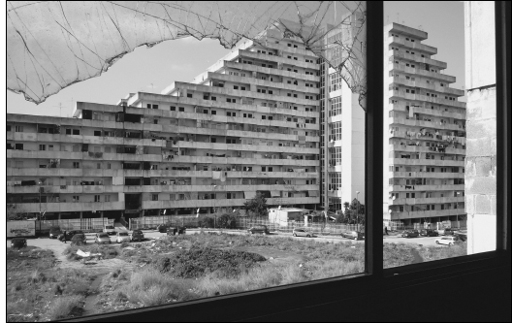

The worst housing project in Europe. The camorra turned the triangular tower blocks of Le Vele (‘The Sails’) into a narcotics shopping mall in the 2000s.

The first fragment of cityscape that springs into the public mind when the word ‘camorra’ is mentioned is no longer the alleys of Forcella. Rather it is a catastrophically failed housing project in the suburb of Scampia. Known as ‘Le Vele’ (‘The Sails’), it consists of a row of massive, triangular apartment blocks built in the sixties and seventies, and designed to reproduce the tight-knit community life of the city-centre alleyways in multiple storeys. The outcome, with its ugly, dark and insecure interior spaces, feels more like a high-security prison without guards. The blocks were very badly built: lifts did not work, concrete crumbled, roofs leaked, and neighbours could hear everything that went on three doors down. These problems had

already tipped Le Vele towards slum status when desperate refugees from the 1980 earthquake illegally occupied vacant apartments—some of them before they were even finished. Before long, residents felt besieged by a minority of drug-dealing

camorristi

. The police presence consisted of sporadic and largely symbolic tours. Residents say that some cops took bribes to leave the drug dealers unmolested. A long-running campaign to have Le Vele emptied and demolished met with a sluggish political response. At the time of writing, of the seven original apartment blocks, four are condemned but still standing—and still partially occupied.