Blood Brotherhoods (78 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The strategic brains behind the Region belonged to Pippo Calderone, whose younger brother Antonino would later turn state’s evidence, giving us a priceless insight into this remarkable phase of mafia history. Pippo Calderone, a businessman and Man of Honour from the eastern Sicilian city of Catania, even went to the trouble of drafting a constitution for the new body. The most important article in that constitution, and the first item on the agenda at the Region’s first meeting, was an island-wide kidnapping ban—on pain of death. The reasons for the ban seemed wise. Kidnappings might be lucrative in the short term, but made the mafia unpopular with civilians. More importantly, they drew down more police pressure—roadblocks and the like—that made life particularly difficult for

mafiosi

who were in hiding from the law. So it was hard for any of the bosses at the Region’s first meeting to disagree with such a statesmanlike measure, and six hands were duly raised to approve it. However, as always in mafia affairs, the kidnapping embargo was a tactical move as well as a practical one: it was aimed at the

corleonesi

, and intended to isolate them within Cosa Nostra. The

corleonesi

, Liggio, Riina and Provenzano, took note.

On 17 July 1975, only a few months after that first meeting of the Region, a little old man was driving an Alfa Romeo 2000 through the crackling heat of a Sicilian summer afternoon. His destination was Salemi, a town clustered round a Norman fortress on a hill in the province of Trapani. But he never reached it: by a petrol pump just outside town, he found the road in front of him blocked by ten men armed with machine guns. As he was being forced out and bundled into another car, the bus from Trapani arrived. Two of the snatch team flagged down the terrified driver and climbed aboard the bus. Silently they then showed their weapons to the passengers. Words were superfluous: nothing had happened, and nobody had seen it happen.

The

corleonesi

had struck again, showing their contempt for the manoeuvres against them in the Region. Moreover, they had struck at a more illustrious victim than ever before. The old man in the Alfa Romeo was Luigi Corleo, a tax farmer. In Sicily, tax collection was privatised and contracted out. Since the 1950s, Corleo’s son-in-law, Nino Salvo, had turned the family tax-collecting business into a vast machine for ripping off Sicilian taxpayers. Together with his cousin, Ignazio, Nino Salvo ran a company that now had a near monopoly on revenue gathering, and took a scandalous 10 per cent commission. In effect, one lire in every ten that Sicilians paid in tax went straight into the pockets of the Salvo cousins. Not only that, but the

Salvos managed to engineer a two- or three-month time-lag between harvesting the taxes and handing them over to the state—two or three months in which these huge sums attracted very favourable interest. The pharaonic profits of the Salvos’ legalised swindle were invested in art (Van Gogh and Matisse, apparently), hotels, land, and in the political support network needed to ensure that the Sicilian Regional Assembly continued to rubber-stamp the tax-collecting franchise. Both Salvo cousins were also Men of Honour, and both were very close to two members of the triumvirate: Tano Badalamenti and Stefano Bontate, the ‘Prince of Villagrazia’. In other words, by kidnapping Luigi Corleo, the

corleonesi

had taken aim at the very heart of economic, political and criminal power in Sicily. Antonino Calderone would later explain that the Corleo kidnapping was ‘an extremely serious matter that created a huge shock in Cosa Nostra’. The ransom demand was shocking too: 20 billion lire (not far off $135 million in 2011 values).

The Corleo kidnapping was initially a grave embarrassment for Badalamenti and Bontate, and quickly become an utter humiliation. Despite sowing the countryside around Salemi with corpses, Badalamenti and Bontate failed to either free the hostage, or find any evidence in support of their suspicion that the

corleonesi

were responsible. To cap it all, old man Corleo died while he was still in captivity, probably from a heart attack. Yet Badalamenti and Bontate proved unable even to recover the body.

The

corleonesi

may not have bagged the ransom they had hoped for, but they did gain something that in the long-term would prove far more valuable: a high-profile demonstration that Badalamenti and Bontate had not mastered the basics of territorial control. Plainly, the

corleonesi

could ignore Cosa Nostra’s lawmakers with impunity. Across Sicily, other mafia bosses heard the rumours and started to draw conclusions.

The brief sequence of high-profile kidnappings in Sicily coincided with one more important development: a new generation of leader took control in Corleone. Luciano Liggio was gradually side-lined by his deputy, Totò ‘Shorty’ Riina, who was ably assisted by Bernardo ‘the Tractor’ Provenzano. Riina it was who directed operations for the Cassina and Corleo kidnappings.

Meanwhile Liggio was still very busy, but in places where Cosa Nostra’s rules against kidnapping did not apply. In July 1971 he moved to Milan, where he could orchestrate the hijacking of as many hostages as he liked. Furthermore, in Milan, there were many more rich people available to abduct. Kidnapping in Sicily was more politically significant than it was lucrative or frequent. Between 1960 and 1978, there were only nineteen

abductions in Sicily, a very small proportion of the terrifying 329 in Italy as a whole. The word inside Cosa Nostra was that Liggio grew fantastically rich on the off-island trade in captives, and that he was working with the organisation that was rapidly becoming the Italian underworld’s kidnapping specialist: the ’ndrangheta.

Cosa Nostra and the camorra were involved in kidnapping to a comparatively limited extent. Cosa Nostra, as we have seen, had severe constitutional reservations about harbouring captives on its own manor.

Camorristi

in the early 1970s performed a number of abductions, but kidnapping did not become a typical camorra crime, probably because they did not have the colonies in the North that would enable them to create a national network for hostage-taking.

To anyone who bothered to read the crime pages of the Calabrian dailies, a pattern of kidnappings had already established itself in the region in the late 1960s. But the victims were all local figures, the ransom demands relatively small, and the periods of captivity short. Things began to change in December 1972 with the abduction of Pietro Torielli, the son of a banker from Vigevano in the northern region of Lombardy. Luciano Liggio and the ’ndrangheta are thought to have been involved. From now on, kidnapping would be a nationwide business for Calabrian organised crime.

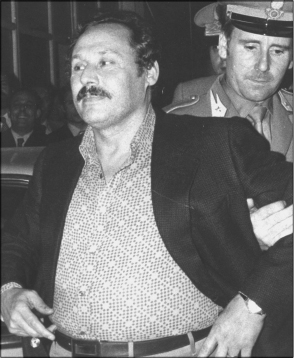

Corleonese kidnap king. Sicilian mafia boss Luciano Liggio ran kidnapping operations in northern Italy with his friends in the ’ndrangheta.

There were several reasons why kidnapping became a favourite business for the ’ndrangheta. It had the great advantage of being cheap to organise, for one thing. The ransoms it rendered often served as seed capital for more investment-intensive initiatives, like construction or wholesale narcotics dealing. No mafia had a network of colonies in the North to match the ’ndrangheta’s. Nor did any other mafia have Aspromonte. The mountain massif at the very tip of the Italian peninsula had long been a reliable refuge for fugitives. Its crags, its grottoes and its wooded gorges became internationally notorious as hiding places for kidnap victims. Captives would report hearing the same distant church bells from their prisons. A bronze statue of Christ on the cross, situated among the beeches and firs of the Zervò plain above Platì, became a kind of post-box where ransoms would often be deposited. For years the statue had a single large bullet hole in its chest. On Aspromonte the ’ndrangheta’s reign of fear and complicity was so complete that the organisation could be confident of keeping hostages almost indefinitely. More than one escaped victim turned to the first passer-by they encountered for help, only to be led back to his kidnappers. The poor ’ndrangheta-controlled mountain villages began to live off the trickle-down profits of kidnapping. Down on the Ionian coast, Bovalino had an entire new quarter known locally as ‘Paul Getty’—after the famous hostage whose abduction first propelled the ’ndrangheta to the forefront of the kidnapping industry.

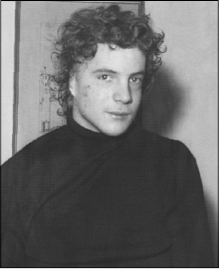

In central Rome, in the early hours of 10 July 1973, John Paul Getty III—the sixteen-year-old, ginger-haired, hippy grandson of American oil billionaire Jean Paul Getty—was bundled into a car, chloroformed and driven away. After an agonising wait, the kidnappers finally communicated their demands in a collage of letters cut out from magazines: ten billion lire, or around $17 million at the time. The eighty-one-year-old Jean Paul Getty, a notoriously reclusive and avaricious man, refused to negotiate: ‘I have fourteen grandchildren, and if I pay a penny of ransom, I’ll have fourteen kidnapped grandchildren.’

The stalemate dragged on until 20 October when the boy’s captors sliced off his right ear, dropped it in a Band Aid packet full of embalming fluid, and mailed it to the offices of the Roman daily newspaper,

Il Messaggero

. The gruesome package included a note promising that the rest of him would ‘arrive in tiny pieces’ if the ransom were not paid. To increase the Getty family’s agony further, the ear was held up by a postal strike and did not arrive for nearly three weeks. The savage mutilation had the desired effect: a month later a ransom amounting to two billion lire ($3,200,000)—a fifth of the sum originally demanded—was deposited with a man wearing a balaclava helmet standing in a pull-off area on the highway.

Kidnap victim. John Paul Getty III was taken in July 1973. His ’ndrangheta captors cut off his ear before releasing him.

John Paul Getty was released. But the psychological impact of his ordeal was profound. He was fragile and very young: he had spent his seventeenth birthday in captivity. The trauma seems to have tipped him into drug and alcohol addiction. In 1983 his liver failed, precipitating a stroke that caused blindness and near total paralysis.

It was never proved beyond all doubt that Luciano Liggio masterminded the Getty kidnapping. Nor, for that matter, was anybody ever convicted apart from a handful of small-time crooks—the hired hands rather than the orchestrators. But one thing is certain nonetheless: Getty was held in the mountains of Calabria, and his captors were Luciano Liggio’s friends in the ’ndrangheta. And once Luciano Liggio was removed from the scene (he was recaptured in 1974 and never freed again), the ’ndrangheta showed that it was more than capable of running highly lucrative kidnapping schemes on its own.