Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (31 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

Aldgate station opened in 1876. This is the northern end of the station with three steam-hauled trains visible. The drivers and firemen of the Metropolitan Railway locomotives needed to be made of stern stuff. The line into the tunnel on the left goes to Aldgate East.

Victor Lorenzo Whitechurch (1868-1933), a clergyman and author, wrote much detective fiction including

Thrilling Stories of the Railway

(1912). This collection contains fifteen stories, the first nine of which feature wealthy amateur investigator Thorpe Hazell, vegetarian and railway hobbyist. The stories vary from theft on the railways (e.g.

The Stolen Necklace

and

Sir Gilbert Murrell’s

Picture

), tobacco smuggling (

Peter Crane’s Cigars

) to foreign spies masquerading as locomotive firemen. He also wrote stories for the

Strand Magazine

and

Railway Magazine

from the 1890s. Whitechurch’s

Murder on the Okehampton

Line

, which appeared in

Pearson’s Magazine

in December 1903, opens with a newspaper report of a murder:

On the arrival of the last train from Exeter to Okehampton at the latter station last night, a gruesome discovery was made. A porter on the platform noticed a gentleman seated in the corner of a third class compartment and, as he made no attempt to get out of the carriage, opened the door to wake him, thinking he might be asleep. To his horror he discovered the man was dead and a subsequent examination revealed the fact that he been stabbed in the heart with some sharp instrument.

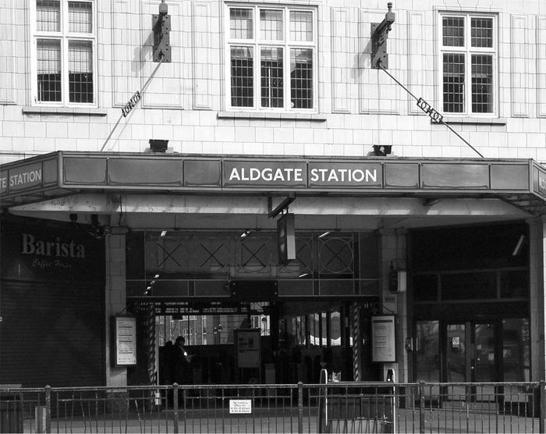

A modern view of Aldgate station frontage. This busy station in the City of London is currently used by trains on the Metropolitan and Circle lines.

As detective Godfrey Page investigates, his line of enquiry begins to resemble somewhat the Monty Python sketch (‘Agatha Christie Timetable’):

Let me see, the last down train arrives at Okehampton at ten-fifty. It’s the one that leaves Waterloo at five-fifty and Exeter, St David’s, at ten-thirty. Of course, the great question is where did he get into the train and whereabouts was he murdered?…These two men…could not have got away by train, for this was the last one at the junction that night…Number 242 third coach is one that is kept at Plymouth as a spare carriage in case there is an abnormal number of passengers for the Paddington express. The night to which you refer it ran – on the eight –twenty p.m. from North Road, Plymouth arriving here at 10.03.

What might seem to be nerdishly intimate knowledge of train timetables is crucial to getting the crime solved.

Murder is the theme of Miles Burton’s

Death in the Tunnel

(1936) which features sleuths Desmond Merrion and Detective Inspector Arnold. They investigate the death of Sir Wilfred Saxonby who is discovered in a

first-class carriage on the London to Stourford train. An eye-witness to a murder provides the opening to

4.50 from Paddington

(1957) by Agatha Christie. A passenger on a train, Elspeth McGillicuddy, who is traveling from Scotland, sees a woman strangled in a passing train. What has happened to the body? Who was the unfortunate victim? Who murdered her and why?

Thomas Hanshew (1857-1914)

The Riddle of the 5.28

. Written in 1910, this is one of the earliest stories to be set on the Brighton line from London. The train compartment becomes the scene of a gruesome discovery and the beginning of a deep and dark mystery. Typically where short stories are concerned there is no time to waste in getting to the point and Hanshew does this to good effect. A stationmaster at Anerley near Crystal Palace receives a communication: ‘Five-twenty-eight down from London Bridge just passed. One first-class carriage compartment in total darkness. Investigate.’ The porter and stationmaster do just that and find the said compartment with an ‘Engaged’ label on the window. As they unlock the door they make a dreadful discovery. ‘For there in a corner, with his face towards the engine, half sat, half leaned the figure of a dead man with a bullet hole between his eyes.’ What follows is an intriguing murder mystery, involving not only a whodunnit but also raising the question of how was it done given that ‘both doors were locked and both window closed’ when the body was discovered.

Travelling on the underground can be a risky enterprise when the threat of murderers and assassins looms. The London Underground, the first part of which commenced operations in 1863 and which now possesses over 250 miles of track and about 288 stations, has provided the setting for many novels and short stories. It is an ideal atmospheric setting for dark tales.

A

Mystery of the Underground

(1897) by John Oxenham (1853-1941), was effective in scaring its readers when it was first published weekly in

To-Day

. The story concerns an assassin who is murdering people every Tuesday night on the underground. The tone is established right from the outset: ‘The underground station at Charing Cross was the scene of considerable excitement on the night of Tuesday the fourth of November. As the 9.17 London & North Western train rumbled up the platform, a lady was standing at the door of one of the first-class carriages, frantically endeavouring to get out, and screaming wildly…she was in a state of violent hysterics.’ Railway cognoscenti will raise their eyebrows at the idea of a London & North Western train being found at Charing Cross.

The presence of a dead body, sitting as though asleep, was the cause of the woman’s desperate behaviour. As another body is discovered a week later at Ealing Broadway station, people are becoming reluctant to take the train. However, the murders do not deter the morbidly curious who crowd the platforms of Charing Cross, Westminster, St James and Victoria ‘simply with the idea of being on the spot in case anything happens.’ These ‘throngs of

people [wait] silently, in a damp fog, peering into carriage after carriage as the almost empty trains rolled slowly, like processions of funeral cars.’ The body count adds up as they fall victim to the mysterious assassin’s deadly bullets.

Cover of

Strand Magazine

which published most of the Sherlock Holmes stories in serial form.

Baroness Emmuska Orczy’s (1865-1947) ‘The Mysterious Death on the Underground Railway’ appeared as a short story in the book

The Old

Man in the Corner

(1909). What appears to be the suicide of a woman in a carriage on the Metropolitan Railway turns out to be a murder. There is some similarity with the discovery of the body to that in

A Mystery of the

Underground.

The guard ‘noticed a lady sitting in the furthest corner, with her head turned away towards the window.’ When the guard asks which station she wants the lady does not move, giving the impression that she is asleep. ‘He touched her arm lightly and looked into her face…In the glassy eyes, the ashen colour of the cheeks, the rigidity of the head, there was the unmistakable look of death.’

The railway carriage proved to be an ideal setting for many situations other than murder such as theft, furtive and clandestine trysts between lovers, secret confabulations between spies and even sexual encounters, planned or entirely casual and spontaneous. Ian Carter quotes the interesting example of frequent quickies between stops: ‘For a few years after 1866, services between Charing Cross and Cannon Street drew a curious traffic. Some ladies of the street had found that the South Eastern Railway’s first-class compartments, combined with the uninterrupted seven-minute run, provided ideal conditions for their activities at a rental that represented only a minute proportion of their income.’ The mind boggles.

As we saw with Sherlock Holmes, the carriage allows the possibility for reflection and even the working out of a murder. In Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957)

The Man with no Face

(1928) the discovery of a murdered man who had his ‘face cut about in the most dreadful manner’ on a beach at East Felpham becomes the topic of debate for passengers on a busy train who speculate about the foul deed. One of the passengers is Lord Peter Wimsey, the gentleman ‘detective’, who proceeds to solve the crime during the journey and beyond, just as you would expect.

Another example is in Agatha Christie’s short story

The Girl in the Train

(1924) which features a dissolute playboy, George Rowland, who has taken a train from Waterloo to a place he spots in an ABC guide called

Rowland’s

Castle

. The journey changes his life dramatically when a beautiful girl bursts into his first-class compartment begging to be hidden from a villainous foreign man who then appears at the window and angrily demands that Rowland gives his niece back. The chivalrous George calls a platform guard who detains the man. The train departs and the adventure begins.

In Dinah Mulock Craik’s (1826-1887)

A Life for a Life

(1859) a passenger notes the perils from drunks of travelling in a carriage late in the day:

I am liable to meet at least one drunken ‘gentleman’ snoozing in his first-class carriage; or, in second class, two or three drunken men, singing, swearing, or pushed stupidly about by pale-faced wives. The ‘gentleman’, often grey-haired, is but ‘merry’, as he is accustomed to be every night of his life; the poor man has only ‘had a drop or two’, as all his comrades are in the habit of taking, whenever they get the chance: they see no disgrace in it…It makes me sick at heart sometimes to see a decent, pretty girl sit tittering at a foul-mouthed beast opposite; or a tidy young mother, with two or three bonnie children, trying to coax home, without harm to himself or them, some brutish husband, who does not know his right hand from his left, so utterly stupid is he with drink.

A more eerie story is Basil Cooper’s

The Second Passenger

(1973) where a man travels in an empty third-class carriage from Charing Cross and reflects on his past. The passenger is not all he seems in this macabre tale of a tall figure, green slime and a porter shouting ‘what was it?’

The success of Britain’s early railways inspired groups of businessmen to plan extensions to the rail system. Many did so with good intentions, others were no more than conmen and criminals. This latter group had no intention of building a railway, despite promises to investors who had lodged money with them. During the 1840s accusations of fraud and corruption abounded. Fraudulent and greedy railway speculators come under critical scrutiny in Anthony Trollope’s (1815-1882)

The Way We Live Now

(1875). The central character, Augustus Melmotte, is a mysterious international financier described as a ‘rich scoundrel… a bloated swindler… and a vile city ruffian’ who desires to be accepted into the influential circles of Victorian society. He believes he has almost achieved this when he convinces a number of prominent London businessmen of a get-rich-quick scheme which turns out to be a corrupt corporation with the impressive name of the Great South Central Pacific & Mexican Railway. Among those convinced are the Carburys, an aristocratic but cash-strapped family desperate to recoup their fortunes by whatever means necessary.

In between the financial goings-on there are romances such as the one-sided romance between Melmotte’s daughter Marie and the dissolute Sir Felix Carbury. The novel also includes the exploits of an American adventuress with a predilection for shooting her lovers. Melmotte manages to get himself accepted into high society as well as being elected as an MP on the strength of his dealings in railway stock which entail borrowing huge sums of money for other ambitious projects. Melmotte is eventually exposed by one of his creditors, Paul Montague, who does not wish to be a part of Melmotte’s fraudulent deals. The railroad company’s stock begins to plunge causing Melmotte’s fortunes to sink as quickly as they rose. Meanwhile his angry creditors try to press for payment on their rapidly sinking investment.