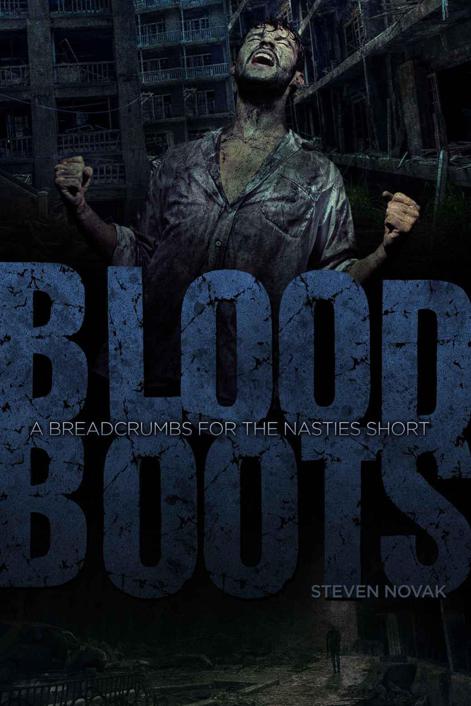

Bloodboots: A Breadcrumbs For The Nasties Short

Read Bloodboots: A Breadcrumbs For The Nasties Short Online

Authors: Steven Novak

Bloodboots

features characters that first appeared in the novel,

MEGAN: BREADCRUMBS FOR THE NASTIES BOOK ONE

. While the story is meant to stand alone, further reading is advised.

1.Copyright © 2014 Quiet Corner Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without prior written permission from the author.

This is a work of fiction. Names, places, and characters are used in a fictitious manner and should not be construed as true events. It is intended for adults only and contains sexually explicit content. All sexually active characters are eighteen or older and not directly related.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised how quickly we turned on each other. We should have seen it coming, everything that happened. It was staring us in the face. The human race is a fickle thing. For all our advancements, we never really evolved. When life became easier to manage, so did we. We lost our claws. Our teeth dulled. We traded who we really were for a life of relaxation. We shoved it to the rear of the closet, buried it in clothing and gadgets and pills to make us forget it existed in the first place: self-imposed ignorance.

We forgot we were animals.

Before the world went to shit, I was a day trader. I spent my days in a world of concepts, ideas and numbers devoid of substance beyond the nonsense we assigned. I dealt in ghosts, moved them around and put them back again. I was good at it, defined my existence by it, and believed I was special because of it. It bought me things, lots of things. If my car was better then my neighbors’, I won. If my apartment was bigger, I let them know it. If my girlfriend had a better ass, I flaunted it. When people looked at me they saw something they wanted and couldn’t have. I was perfect, a golden god atop a temple of green. I made them jealous. Publically they claimed to hate everything I stood for. Privately they wished they were me. That’s just the way it was. There’s no denying it. When I looked at them I saw numbers, price tags, and name brands, comparisons. They existed to be judged against, to confirm what I already knew, to feed my ego.

The Crash of ’38 was an end to the fun. It took almost everything, nearly cleaned me out. My girlfriend took the rest. When I couldn’t buy her things, I no longer served a purpose. Our relationship wasn’t really a relationship at all. It was an agreement. I was fine with that. We both knew it. Physically she was out of my league, flawless, feminine yet firm in a way that made every inch of me ache. She was out of everyone’s league. Her body was perfect, the best money could buy. My wallet was long, and thick, and gorgeous. Without it she wouldn’t have given me the time of day. She was willing to spend her nights on her back because she could spend her days wrapped in money. Made sense to me. Nature has always paired the strong with the strong, best with the best. For a period of time that’s exactly what we were. We had so many things to prove it.

Strength meant something very different then.

The fallout from the crash was bigger than any of us expected. Everything had been tied together, one economy for one world, the glorious beginnings of a utopia built on the common ground of greed. Suddenly the numbers we created were working against us, fictional constructs given a life of their own, taking on meanings we never intended. They were fighting back. The comforts of the middle, the things that kept them docile and manageable, went away. The bottom swelled, spread into areas they weren’t meant to, learned things they were better not knowing. The protests came first and riots shortly after, the desperate blows of desperate people. They were hungry. They were tired. They’d had enough.

The animals had found their teeth.

Groups emerged, old and new. Differences became a reason to hate. Hate became a pastime. I’m not even sure who fired the first missile, or where it landed, or how many died. No one is. Honestly, it doesn’t matter. When it happened, it happened quickly, couldn’t be taken back. A country I’d never heard of was suddenly gone, half its bordering neighbor blown off the map. There wasn’t any fallback plan or secret strategy for victory. There was only survival: them against us, us against the world. They pushed a button and they just kept pushing.

The one with the most bombs wins.

The first sentence in the epitaph of the human race.

When they exhausted their bombs they turned to gas. When the gas was gone they got creative, secret things created in secret labs by men just looking for a way to send their kids to college. They didn’t know what they were making, never imaged any of it would actually get used. They certainly never thought the fallout would have the effect it did. It was just science, knowledge for the sake of knowledge, steps on the stairway to something better. They were wrong. Anything capable of killing was used to kill, to win. No matter how awful it was.

When I first heard stories of the dead coming back, I didn’t believe a word of it. Even after everything that had happened, it still seemed silly. I changed my mind when I watched a ten year-old kid take a bite out of his mother’s leg. He just bit it, chewed, swallowed, and went back for more. I never forgot the look on her face, confusion mixed with horror, the sad realization of ending. Instead of helping, I ran.

What would’ve been the point?

I only survived because of luck. I’d love to tell you there was more to it, but there wasn’t. The bombs didn’t land on my head. It’s as simple as that. When money still meant something I had some, a little. I used it. When I pulled Patrick from his home the place was working with a skeleton crew, volunteers without family of their own, refusing to leave, silly people fighting a hopeless battle. Eventually they’d be forced to leave. They wouldn’t have a choice. The city was crumbling. Little boys were eating their mothers.

A month later there wasn’t anything left.

I used my connections to get Patrick out of the city before the gimps made it theirs. We wound up at a military outpost, packed into barracks like prisoners, living off rations, side-by-side with the wealthy turned poor. Some of us believed it was only a matter of time before things returned to normal. I was one of them. It seemed reasonable. Things had been bad before. There were wars, and plagues, and all sorts of nastiness. The human race loved to fuck itself. We were good at it.

But we always came back. It never ended us. This was just another bump in the road, a detour on the journey to greener pastures. I actually believed I’d see my apartment again, the city, maybe bang a beautiful girl.

I was an idiot.

When delivery of rations to the base began to slow, the mood changed. The men with the guns were more in charge than ever. Suddenly our money didn’t matter. Communications with the outside dwindled. Stories of life beyond the base grew stranger. The dead weren’t just coming back. They were changing.

“A god damn monster, fifteen feet tall, covered in fur.”

“Sons of bitches are draining the blood from people and leaving them on the side of the road.”

“Tore him to pieces…nothing left.”

At the time they just seemed like stories, nonsensical ravings of the bored and hysterical. Even in a world of the absurd they seemed absurd.

They were also true.

Eight months after arriving at the base, it was clear we needed to leave. It wasn’t safe, not for me, especially not for Patrick. The guards had grown sick of us. We were a drain on their resources, extra mouths that needed feeding, pampered-rich and useless, offering nothing in return. We’d overstayed our welcome.

Patrick’s situation didn’t make things easier. When my little brother was born, he was dead. The umbilical cord knotted itself, wrapped around his neck while still in the womb. The thing keeping him alive literally choked him to death. They worked on him for seven minutes, pumping air into the lungs of a corpse. He wasn’t supposed to come back. Seven minutes is a long time.

It wasn’t long enough.

I resented Patrick growing up. I’m not proud of it. I hated the way people looked at him, the way they looked at me because of him. My brother was a Bertie, one of the first. Berthold’s Syndrome took everything from him. The disease was relatively new at the time. There were always specialists around. Everyone wanted to study him, hook him to machines, make some notes and write a paper. His pain held the prospect of income, fame, maybe an award. If there was anyone who actually wanted to help, I never met them. When they’d written everything they could write, they went away.

Patrick stood out because he was different. When strangers met him, they pitied him. When they learned I was his brother they pitied me.

I was twenty-three when my parents died, a car crash. Some drunk sideswiped them, crushed my mother’s chest, and drove a piece of metal through my father’s skull. And that was that. The care of Patrick fell to me. I didn’t ask for it, didn’t want it. There was no one else. Instead of dealing with my brother I hid him away, pretended he didn’t exist. It was easier for both of us.

I’m not entirely sure why I picked him up when everything went to shit. Maybe I felt bad. Maybe I just couldn’t let him die. I don’t know. Maybe it was just something I did.

I spent so many years in the company of assholes; maybe I wanted to be near something different.

Locked away in our barracks without the proper medication, Patrick’s Berthold’s became impossible to manage. He was always in pain. He needed pills the soldiers were no longer offering. The sympathy they showed earlier in the year was gone. When they looked at him they whispered, heads shaking, eyes rolling. He was a drag on their resources, useless in the reality of the new world. We all were.

Unfortunately, leaving wasn’t an option. During the first year the base was under constant attack. All day long the gimps clawed the fences and scraped the walls, sunken faces, eyes without pupils, milky white and distant. More arrived by the hour, the reanimated dead. They never stopped coming, groups of a hundred and more, packed together, desperately searching for a way inside, hungry. Confident the walls would hold and desperate to conserve ammunition, the soldiers eventually stopped shooting. The gunfire was only drawing the nasties in. Instead they patrolled the fences in groups, stabbing through chain links with knives, bodies piled atop bodies, everything rotting. At first the stench was unbearable. In time it became the norm.

The bastards never stopped moaning and screeching in that low, guttural way they screeched. I hated that screech.

Between Patrick and the gimps, sleeping was impossible. I’d lie awake at night, listening to them scratch, rotten fingernails snapping, teeth scraping concrete. Every night was a repeat of the last, unending, unchanging, as constant as the moon. After a while I was able to pick specific voices from the crowd and gave them names: Fred was a deep moaner. Mark hit the high notes. There was something almost sexual about Janice—high-pitched, building to something she could never reach, a frustrated housewife in need of a spanking. I liked Janice. Things went on like this for months, everything the same—until the night it was different.

One night, something new joined the chorus.

The howling came from the forest to the west; it was unlike anything we’d heard, louder and more guttural, almost like a dog if a dog could scream. Whatever they were, they weren’t gimps. The next morning the guards were on edge, weapons higher than normal, fingers dancing along triggers.

I was waiting in line for water rations when I overheard two of them talking. I shouldn’t have been listening; I was asking for trouble, so I did my best to remain discreet.

“Cap wants to send someone out there.”

“Fuck that. Ain’t no one doing that shit.”

“Says he wants to know what it is, thinks it’s worth checking out.”

“Cap’s lost his fucking mind if he th—”

I wasn’t discreet enough. Suddenly there was a rifle in my back, hot breath in my ear. The instant the pair surrounded me the line for water ceased to exist. I was alone.

The guy behind me was massive: dark skin, darker beard, a mountain of hormones and muscle with a four-inch scar across his cheek. “Got a problem, Hoss?”