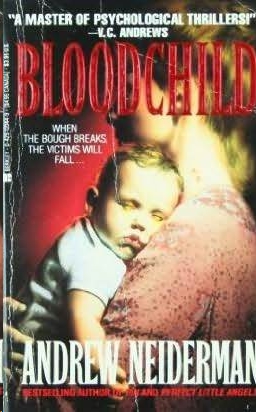

Bloodchild

By

Andrew Neiderman

CONTENTS

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Epilogue

For Uncle Dave, who will always be the judge

BLOODCHILD

A Berkley Book / published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY

Berkley edition / September 1990

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1990 by Andrew Neiderman.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

ISBN: 0-425-12044-9

A BERKLEY BOOK® TM 757,375

Berkley Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

The name "BERKLEY" and the "B" logo are trademarks belonging to Berkley Publishing Corporation.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

"… And the midwife wondered and the women cried, 'Oh, Jesus bless us, he is born with teeth.'"

—Henry VI, Part III

William Shakespeare

Even before Dr. Friedman looked up, Dana Hamilton knew her baby was dead. She had sensed something happening throughout the delivery. The spiritual bond between mother and child had been broken. She had felt her baby's life break away and drift off like a kite whose string had torn. She was left with the same empty, loose feeling in her hands.

Her husband, Harlan, wearing the milk-white surgical mask, his forehead beaded with sweat, stared at her along with Dr. Friedman and the nurses. They all had the same eyes peering over their masks. Although the faces were covered, everyone's eyes reflected the morbid conclusion.

"I don't understand it," Dr. Friedman said. "It must have been the trauma of the birth."

With his mouth hidden from view, his voice sounded distant to Dana. It was almost as if he were a narrator, physically apart from the tragic scene being acted out before her.

Harlan moved quickly to her side and lowered his surgical mask. His face was now seized with fear, as well as with horror. She looked from him to Dr. Friedman to the nurses and back to Harlan. She saw the corpse of her baby being lifted and handed gently to a nurse, who, because of her years of training, automatically handled it with care despite its silent heart.

When Dr. Friedman lowered his mask like a flag lowered in defeat, she began to scream and scream and scream.

Some time later Dana awoke in her hospital room. For a moment it seemed as if she had been dreaming and all that had happened was only a nightmare. Harlan was standing by the window looking down at the parking lot, his hands clasped behind his back the way they usually were when he lectured to his English students at the community college. But with his shoulders slumped, his chin nearly on his chest, he looked much older than his thirty-seven years and nowhere near his six feet two inches. His demeanor confirmed their tragedy. It had been no nightmare.

Dana moaned, and he turned around quickly to come to her bedside.

"Harlan…"

"Don't cry, don't cry. Don't make yourself sicker. Please, I can't lose you too," he said, as if there really were a chance of that. She was weak, but she knew she wasn't in critical condition. He was just being overly dramatic, the way he could be, she thought; but she didn't dislike him for it. It seemed appropriate at that time.

"Why did this happen?"

"They're doing an autopsy now. From what Dr. Friedman told me, the baby's heart stopped beating as the child was emerging."

"But it was going so well," she said, her face crumpling. "He said I was one of the healthiest thirty-five-year-old pregnant women he ever had."

"And you were. It's not your fault. Don't lay there and blame yourself. Please," he pleaded.

"But we wanted a child so badly, Harlan." She closed her eyes and relived the way Dr. Friedman had handed her dead baby to the nurse. "What was it?" she asked in a whisper.

"It was a boy," he said. He smiled as if she had given birth to a healthy, living boy.

"Oh, God." She turned away, pressing her face into the pillow. He stroked her long, light brown hair gently, but she didn't want to be comforted. She realized she was more angry than sad. This was unfair; this was illogical. She had done everything right—the vitamins, the good foods, the avoidance of anything in any way detrimental, the exercise classes, all the preparation—it was unfair. They had been cheated, betrayed, made the object of some terrible celestial joke. God was having fun with them at their expense. Why?

She was going to breast-feed the child; she had read up on the advantages and had come to believe there was truth in the idea that breast feeding developed a stronger bond between mother and child. She had read a lot about child rearing. There were all those books, the videotapes, the magazines, even the classes she'd attended. All for what?

"It's just not fair, Harlan," she said, turning back to him. "It's just not right."

"I know," he said. He took her hand and squeezed it gently, but she could see by the way he was looking at her that he had more to say.

"Was there something I did that was wrong?"

"No, no—God, no. Dr. Friedman told me over and over that you were a great patient. You did everything on the money. He's as disgusted as we are, and as confused."

"Then what is it, Harlan? There's something else, something you want to tell me. What?"

"Well, it's strange, but it's almost as if…as if it were fated. Just don't reject it outright," he said quickly, holding both hands up, palms toward her. "I thought I would, but as I stood here watching you and waiting for you to regain consciousness, I couldn't help going over and over it and wondering if it wasn't meant to be."

"What, Harlan? What's meant to be? The death of our child? You want me to accept it as something called fate?"

"No, no. There's a man outside, waiting in the lobby. He's a lawyer, a Mr. Lawrence, Garson Lawrence. He represents a family whose unmarried teenage daughter just gave birth to a baby boy."

"What?" She stared up at him. For some reason all the colors in his face looked more vivid to her. His blue eyes were brighter and his carrot-colored hair seemed more orange. Even the freckles in his forehead looked more abundant to her. "What are you saying?"

"They want to give up the child immediately. Apparently the girl's mother is one of those who believes in breast feeding, too—religiously, in fact—and when Lawrence heard that was what you were going to do… well, he came right to me and made the offer."

She didn't say anything. She stared up at him. He shrugged.

"I know it's a horrible thing to think about at this moment, but there are obvious reasons to make a quick decision. I feel that if we did it, we would have more of a sense of the child being ours."

"But it's not ours," she said, grimacing.

"I know," he said softly, closing and then opening his eyes. "It wasn't easy for me to bring this up at this moment, but as I said, I was standing here thinking… could this be fated?"

"Oh, God, Harlan, I don't know. I don't know." She turned away. Why had such a decision been presented to her now? Was Harlan right? Was it part of some divine design?

"We wanted a child very badly, Dana. This one doesn't have a mother yet, and if you bring its lips to your breast now—"

"Who are these people?" she demanded. Her child had been taken from her—literally ripped out of their lives before they even had a chance to accept it, and here were these people, eager to give their child away. The irony… the unfairness…

"We don't know them. They came here to have the child, to protect their reputation back where they live. They want nothing from us. There's no money involved, nothing but our promise to breast-feed the child."

He looked down quickly, and then up again.

"I saw the baby, Dana. It's a beautiful little boy; he's what our baby should have been. And you won't believe this," he added, smiling widely, "but he has carrot-colored hair. I know it's just a coincidence, but…"

"I don't know what to say. It's all so bizarre. Why couldn't things have gone well for us? Why?" she demanded. Harlan looked away. She realized he was in pain, too, and she softened. "Did you call my mother?"

"I haven't told anyone the bad news yet. My sister called from school, but I told her nothing had happened yet."

"You're not suggesting we pretend this other baby is really ours, are you, Harlan?" she asked, pulling herself into more of a sitting position. She understood that to him the idea was viable.

"In a very short time we might very well think of the child as ours. I almost feel as if our baby's soul moved right over into this one."

Unable to speak, she stared at him, her eyes wide.

"If you saw the child," he said, "maybe…"

"You don't think I'll be able to have another baby, do you, Harlan? No matter what Dr. Friedman said about my health during this pregnancy?" For a moment he didn't reply.

"I don't know what to think, Dana. Neither do the doctors, if you want to know the truth. They didn't anticipate this, did they?"

She thought for a moment.

"All these people care about is that I breast-feed the child?" The possibility was becoming real to her.

"That's what Mr. Lawrence says. They feel guilty about giving it up, of course, and want to be sure it's got a healthy, happy start in life, is the way he explained it. It's all so horrible, but I agree with him—the quicker a decision is made, the better it will be for the baby and for us," Harlan added with more enthusiasm.

She turned away and thought about her own dead baby. She hadn't really looked that hard at him, and she hadn't seen his face. Could she pretend? Could she cheat fate? Could she right the wrong that had been done to them?

She turned back to Harlan. He looked so confused, so tired, so defeated. These should have been the happiest moments of their five-year marriage. Once again she thought, It isn't fair. Once again she was more angry than sad.

Her decision was impulsive but determined.

"Tell him yes," she said, "and have them bring the baby to me when it's time for its first feeding."

Harlan nodded, and for the first time all day he risked a smile. She lifted her arms toward him and they embraced.

"But I can't help telling you," she said, "that I'm frightened."

"Of what?" he asked. "A baby?"

"I don't know." She pulled back and then smiled up at him. "You're right," she said. "That's silly," she added, and she let the moment pass.

Which was something they would both live to regret.

Dana left the maternity ward of Sullivan County General Hospital with the infant cradled possessively in her arms. She had no reason to feel threatened; it was just something instinctive, something she couldn't help. The nurses and other hospital personnel past whom she was wheeled on her way to the lobby and exit all smiled warmly. She sensed that hospital employees, who were usually acquainted with the sick and the infirm, were elated by the birth of children. There was a reaffirmation of life, hope, and purpose in each healthy, newborn baby. Sunshine emanated from the maternity ward. The scents and the sounds from it had been heartwarming and had provided some respite from the sounds of heart monitors and the scents of medication and alcohol. Hospitals could be the entranceways to life, as well as the portals to death.

She was happier than ever, and more confident that she and Harlan had made the right decision. As she was wheeled on, she imagined what it would have been like for her to be leaving this hospital without a baby. Pregnancy would have been more like an illness, something from which she had recovered but which had left her weak and diminished. There would have been no smiles, just expressions of pity and sorrow. She would have had to travel through a funereal atmosphere and exit from a tunnel of grief. The pregnancy and her delivery would have been like some nightmare to repress.