Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (21 page)

In October and November 1937, before the camps and special settlements were full, wives were exiled to Kazakhstan after their husbands were shot. During these weeks the NKVD often abducted Polish children over the age of ten and took them to orphanages. That way they would certainly not be raised as Poles. From December 1937, when there was no longer much room in the Gulag, women were generally not exiled, but were left alone with their children. Ludwik Piwiński, for example, was arrested while his wife was giving birth to their son. He could not tell her his sentence, as he was never allowed to see her, and only learned it himself on the train: ten years felling trees in Siberia. He was one of the lucky ones, one of those relatively few Poles who was arrested but who survived. Eleanora Paszkiewicz watched her father being arrested on 19 December 1937, and then watched her mother giving birth on Christmas Day.

32

The Polish operation was fiercest in Soviet Ukraine, in the very lands where deliberate starvation policies had killed millions only a few years before. Some Polish families who lost men to the Terror in Soviet Ukraine had already been horribly struck by the famine. Hanna Sobolewska, for example, had watched five siblings and her father die of starvation in 1933. Her youngest brother, Józef, was the toddler who, before his own death by starvation, had liked to say: “Now we will live!” In 1938 the black raven took her one surviving brother, as well as her husband. As she remembered the Terror in Polish villages in Ukraine: “children cry, women remain.”

33

In September 1938, the procedures of the Polish operation came to resemble those of the kulak operation, as the NKVD was empowered to sentence, kill, and deport without formal oversight. The album method, simple as it was, had become too cumbersome. Even though the albums had been subject to only the most cursory review in Moscow, they nevertheless arrived more quickly than they could be processed. By September 1938 more than one hundred thousand cases awaited attention. As a result, “special troikas” were created to read the files at a local level. These were composed of a local party head, a local NKVD chief, and a local prosecutor: often the same people who were carrying out the kulak operation. Their task was now to review the accumulated albums of their districts, and to pass judgment on all of the cases. Since the new troikas were usually just the original dvoika plus a communist party member, they were just approving their own previous recommendations.

34

Considering hundreds of cases a day, going through the backlog in about six weeks, the special troikas sentenced about 72,000 people to death. In the Ukrainian countryside, the troikas also operated now as they had in the kulak operation, sentencing and killing people in large numbers and in great haste. In the Zhytomyr region, in the far west of Soviet Ukraine near Poland, a troika sentenced an even 100 people to death on 22 September 1938, then another 138 on the following day, and then another 408 on 28 September.

35

The Polish operation was in some respects the bloodiest chapter of the Great Terror in the Soviet Union. It was not the largest operation, but it was the second largest, after the kulak action. It was not the action with the highest percentage of executions among the arrested, but it was very close, and the comparably lethal actions were much smaller in scale.

Of the 143,810 people arrested under the accusation of espionage for Poland, 111,091 were executed. Not all of these were Poles, but most of them were. Poles were also targeted disproportionately in the kulak action, especially in Soviet Ukraine. Taking into account the number of deaths, the percentage of death sentences to arrests, and the risk of arrest, ethnic Poles suffered more than any other group within the Soviet Union during the Great Terror. By a conservative estimate, some eighty-five thousand Poles were executed in 1937 and 1938, which means that one-eighth of the 681,692 mortal victims of the Great Terror were Polish. This is a staggeringly high percentage, given that Poles were a tiny minority in the Soviet Union, constituting fewer than 0.4 percent of the general population. Soviet Poles were about forty times more likely to die during the Great Terror than Soviet citizens generally.

36

The Polish operation served as a model for a series of other national actions. They all targeted diaspora nationalities, “enemy nations” in the new Stalinist terminology, groups with real or imagined connections to a foreign state. In the Latvian operation some 16,573 people were shot as supposed spies for Latvia. A further 7,998 Soviet citizens were executed as spies for Estonia, and 9,078 as spies for Finland. In sum, the national operations, including the Polish, killed 247,157 people. These operations were directed against national groups that, taken together, represented only 1.6 percent of the Soviet population; they yielded no fewer than thirty-six percent of the fatalities of the Great Terror. The targeted national minorities were thus more than twenty times as likely to be killed in the Great Terror than the average Soviet citizen. Those arrested in the national actions were also very likely to die: in the Polish operation the chances of execution were seventy-eight percent, and in all of the national operations taken together the figure was seventy-four percent. Whereas a Soviet citizen arrested in the kulak action had an even chance of being sentenced to the Gulag, a Soviet citizen arrested in a national action had a three-in-four chance of being shot. This was perhaps more an accident of timing than a sign of especially lethal intent: the bulk of the arrests for the kulak action was earlier than the bulk of the arrests for the national actions. In general, the later in the Great Terror that a citizen was arrested, the more likely he was to be shot, for the simple reason that the Gulag lacked space.

37

Although Stalin, Yezhov, Balytskyi, Leplevskii, Berman, and others linked Polish ethnicity to Soviet security, murdering Poles did nothing to improve the international position of the Soviet state. During the Great Terror, more people were arrested as Polish spies than were arrested as German and Japanese spies together, but few (and very possibly none) of the people arrested were in fact engaged in espionage for Poland. In 1937 and 1938, Warsaw carefully pursued a policy of equal distance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Poland harbored no plans for an offensive war with the Soviet Union.

38

But perhaps, Stalin reasoned, killing Poles could do no harm. He was right to think that Poland would not be an ally with the Soviet Union in a war against Germany. Because Poland lay between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, it could not be neutral in any war for eastern Europe. It would either oppose Germany and be defeated or ally with Germany and invade the Soviet Union. Either way, a mass murder of Soviet Poles would not harm the interests of the Soviet Union—so long as the interests of the Soviet Union had nothing to do with the life and well-being of its citizens. Even such cynical reasoning was very likely mistaken: as puzzled diplomats and spies noted at the time, the Great Terror diverted much energy that might usefully have been directed elsewhere. Stalin misunderstood the security position of the Soviet Union, and a more traditional approach to intelligence matters might have served him better in the late 1930s.

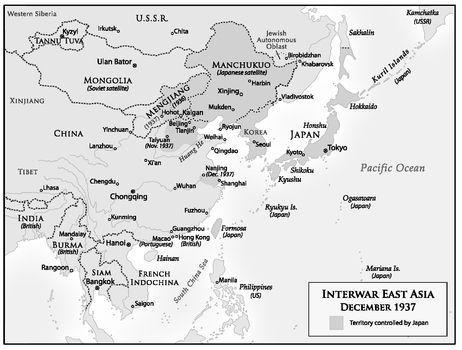

In 1937 Japan seemed to be the immediate threat. Japanese activity in east Asia had been the justification for the kulak operation. The Japanese threat was the pretext for actions against the Chinese minority in the Soviet Union, and against Soviet railway workers who had returned from Manchuria. Japanese espionage was also the justification for the deportation of the entire Soviet Korean population, about 170,000 people, from the Far East to Kazakhstan. Korea itself was then under Japanese occupation, so the Soviet Koreans became a kind of diaspora nationality by association with Japan. Stalin’s client in the western Chinese district of Xinjiang, Sheng Shicai, carried out a terror of his own, in which thousands of people were killed. The People’s Republic of Mongolia, to the north of China, had been a Soviet satellite since its creation in 1924. Soviet troops entered allied Mongolia in 1937, and Mongolian authorities carried out their own terror in 1937-1938, in which 20,474 people were killed. All of this was directed at Japan.

39

None of these killings served much of a strategic purpose. The Japanese leadership had decided upon a southern strategy, toward China and then the Pacific. Japan intervened in China in July 1937, right when the Great Terror began, and would move further southward only thereafter. The rationale of both the kulak action and these eastern national actions was thus false. It is possible that Stalin feared Japan, and he had good reason for concern. Japanese intentions were certainly aggressive in the 1930s, and the only question was about the direction of expansion: north or south. Japanese governments were unstable and prone to rapid changes in policy. In the end, however, mass killings could not preserve the Soviet Union from an attack that was not coming.

Perhaps, as with the Poles, Stalin reasoned that mass killing had no costs. If Japan meant to attack, it would find less support inside the Soviet Union. If it did not, then no harm to Soviet interests had been done by preemptive mass murder and deportation. Again, such reasoning coheres only when the interests of the Soviet state are seen as distinct from the lives and well-being of its population. And again, the use of the NKVD against internal enemies (and against itself) prevented a more systematic approach to the actual threat that the Soviet Union faced: a German attack without Japanese or Polish assistance and without the help of internal opponents of Soviet rule.

Germany, unlike Japan and Poland, was indeed contemplating an aggressive war against the Soviet state. In September 1936, Hitler had let it be known to his cabinet that the main goal of his foreign policy was the destruction of the Soviet Union. “The essence and the goal of Bolshevism,” he claimed, “is the elimination of those strata of mankind which have hitherto provided the leadership and their replacement by world Jewry.” Germany, according to Hitler, would have to be ready for war within four years. Thus Hermann Göring took command in 1936 of a Four-Year Plan Authority, which would prepare the public and private sectors for an aggressive war. Hitler was a real threat to the Soviet Union, but Stalin seems not to have abandoned hope that Soviet-German relations could be improved. For this reason, perhaps, actions against Soviet Germans were milder than those against Soviet Poles. Some 41,989 people were shot in a German national operation, most of whom were not Germans.

40

In these years of the Popular Front, the Soviet killings and deportations went unnoticed in Europe. Insofar as the Great Terror was noticed at all, it was seen only as a matter of show trials and party and army purges. But these events, noticed by specialists and journalists at the time, were not the essence of the Great Terror. The kulak operations and the national operations were the essence of the Great Terror. Of the 681,692 executions carried out for political crimes in 1937 and 1938, the kulak and national orders accounted for 625,483. The kulak action and the national operations brought about more than nine tenths of the death sentences and three quarters of the Gulag sentences.

41

The Great Terror was thus chiefly a kulak action, which struck most heavily in Soviet Ukraine, and a series of national actions, the most important of them the Polish, where again Soviet Ukraine was the region most affected. Of the 681,692 recorded death sentences in the Great Terror, 123,421 were carried out in Soviet Ukraine—and this figure does not include natives of Soviet Ukraine shot in the Gulag. Ukraine as a Soviet republic was overrepresented within the Soviet Union, and Poles were overrepresented within Soviet Ukraine.

42

The Great Terror was a third Soviet revolution. Whereas the Bolshevik Revolution had brought a change in political regime after 1917, and collectivization a new economic system after 1930, the Great Terror of 1937-1938 involved a revolution of the mind. Stalin had brought to life his theory that the enemy could be unmasked only by interrogation. His tale of foreign agents and domestic conspiracies was told in torture chambers and written in interrogation protocols. Insofar as Soviet citizens can be said to have participated in the high politics of the late 1930s, it was precisely as instruments of narration. For Stalin’s larger story to live on, their own stories sometimes had to end.

Yet the conversion of columns of peasants and workers into columns of figures seemed to lift Stalin’s mood, and the course of the Great Terror certainly confirmed Stalin’s position of power. Having called a halt to the mass operations in November 1938, Stalin once again replaced his NKVD chief. Lavrenty Beria succeeded Yezhov, who was later executed. The same fate awaited many of the highest officers of the NKVD, blamed for the supposed excesses, which were in fact the substance of Stalin’s policy. Because Stalin had been able to replace Yagoda with Yezhov, and then Yezhov with Beria, he showed himself to be at the top of the security apparatus. Because he was able to use the NKVD against the party, but also the party against the NKVD, he showed himself to be the unchallengeable leader of the Soviet Union. Soviet socialism had become a tyranny where the tyrant’s power was demonstrated by the mastery of the politics of his own court.

43