Bloody Crimes (2 page)

In the spring of 1865, in the first week of April, he also had much to do. The future was uncertain. His capital city could no longer be defended and might fall to invading Union armies within days, even hours. To save his country, he had to abandon the president’s mansion and flee Richmond. He could take little with him. Soon he would leave behind almost all he loved, including his five-year-old son, Joseph, who had died in his White House in 1864 and now rested in the sacred grounds of the city’s Hollywood Cemetery, where many Confederate heroes, including General J. E. B. Stuart, were also buried. Perhaps one day Jefferson Davis would return to claim the boy, but for now, he had to go on ahead.

O

n the morning of Sunday, April 2, 1865, President Jefferson Davis walked, as was his custom, from the White House of the Confederacy to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, where Robert E. Lee and his wife worshipped and where Davis was confirmed as a member of the parish in 1861. Everything that day appeared beautiful and serene. The air smelled of spring, and the fresh green growth promised a season of new life. One of the worshippers, a young woman named Constance Cary, recalled that on this “perfect Sunday of the Southern spring, a large congregation assembled as usual at St. Paul’s.”

Richmond did not look like a city at war, but it had become a symbol of the conflict. As the capital city of the Confederate States of America, it was the seat of slavery’s and secession’s empire, one of the loveliest cities in the South, the spiritual center of Virginia’s aristocracy and of the rebellion, and, for the entire bloody Civil War that had cost the lives of more than 620,000 men, a strategic obsession in the popular imagination of the Union.

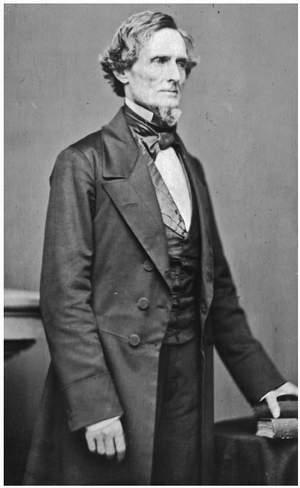

JEFFERSON DAVIS AT THE HEIGHT OF HIS POWER.

Despite Richmond’s vulnerable proximity to Washington, D.C.—the White House of the Confederacy stood less than one hundred miles from Lincoln’s Executive Mansion—the Confederate capital had defied capture. Unlike the unfortunate citizens of New Orleans, Vicksburg, Atlanta, Savannah, Mobile, and Charleston, whose homes had been besieged and prostrated, the people of Richmond had never suffered bombardment, capture, or surrender. In the spring of 1861, Yankee volunteers had naively and boastfully cried, “On to Richmond,” for it seemed, at the beginning, that victory would be so easy. Many in the North believed that Richmond would fall quickly, ending the rebellion before it could even achieve much momentum.

But four years and oceans of blood later, the fighting continued and no Yankee invaders had breached Richmond’s defenses. Not one enemy artillery shell had bombarded its stately residences, war factories, and government buildings. No blackened, burned-out ruins marred the handsome architectural streetscapes. And from the highest point in the city of the seven hills, no advancing federal armies were visible on the horizon. No, Richmond had been spared many of the horrors of war, the physical devastation and humiliating enemy occupation that had befallen many of the great cities of the South.

This morning as the Reverend Dr. Charles Minnigerode, a larger-than-life figure in Richmond society, was conducting services, a messenger entered the church. He carried a dispatch to the president that had arrived in Richmond at 10:40

A.M.

It was a telegram from General Lee, bringing to the president’s church pew news of a double calamity: The Union army was approaching the city gates, and the glorious Army of Northern Virginia was powerless to stop them.

Davis described the scene: “On Sunday, the 2d of April, while I was in St. Paul’s church, General Lee’s telegram, announcing his speedy withdrawal from Petersburg, and the consequent necessity for evacuating Richmond, was handed to me.”

The telegram was not addressed to Davis, but to Confederate secretary of war John C. Breckinridge, vice president of the United

States from 1857 to 1861 during James Buchanan’s administration. On March 4, 1861, Breckinridge’s fellow Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office as president, and he heard the new commander in chief deliver his inaugural address. “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies,” Lincoln had said to the South that day. Now Breckinridge had received a telegram warning him that the Union army was approaching and the government would likely have to abandon the capital that very night, in less than fourteen hours.

Headquarters,

April 2, 1865

General J. C. Breckinridge:

I see no prospect of doing more than holding our position here till night. I am not certain that I can do that. If I can I shall withdraw tonight north of the Appomattox, and if possible it will be better to withdraw the whole line tonight from James River. Brigades on Hatcher’s Run are cut off from us. Enemy have broken through our lines and intercepted between us and them, and there is no bridge over which they can cross the Appomattox this side of Goode’s or Beaver’s, which are not very far from the Danville Railroad. Our only chance, then of concentrating our forces, is to do so near Danville Railroad, which I shall endeavor to do at once. I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight. I will advise you later, according to circumstances.

R. E. Lee

On reading the telegram, Davis did not panic, though the distressing news drained the color from his face. Constance Cary, who would later marry the Confederate president’s private secretary, Colonel Burton Harrison, watched Davis while he read the telegram:

“I happened to sit in the rear of the President’s pew, so near that I plainly saw the sort of gray pallor that came upon his face as he read a scrap of paper thrust into his hand by a messenger hurrying up the middle aisle. With stern set lips and his usual quick military tread, he left the church.”

Davis knew his departure would attract attention, but he noted, “the people of Richmond had been too long beleaguered, had known me too often to receive notes of threatened attacks, and the congregation of St. Paul’s was too refined, to make a scene at anticipated danger.”

“Before dismissing the congregation,” Cary remembered, “the rector announced to them that General Ewell had summoned the local forces to meet for the defence of the city at three in the afternoon…a sick apprehension filled all hearts.”

Worshippers, including Miss Cary, gathered in front of St. Paul’s: “On the sidewalk outside the church, we plunged at once into the great stir of evacuation, preluding the beginning of a new era. As if by a flash of electricity, Richmond knew that on the morrow her streets would be crowded by her captors, her rulers fled, her government dispersed into thin air, her high hopes crushed to earth. There was little discussion of events. People meeting each other would exchange silent hand grasps and pass on. I saw many pale faces, some trembling lips, but in all that day I heard no expression of a weakling fear.”

Davis’s calm notwithstanding, news of Lee’s imminent retreat alarmed the people of Richmond. Many denied it credence. General Lee would not allow it to happen, they told themselves. He would save the city, just as he had repelled all previous Union efforts to take it. In the spring of 1865, Robert E. Lee was the greatest hero in the Confederacy, more popular than Jefferson Davis, whom many people blamed for their country’s misfortunes. This news was not completely unexpected by Davis and others in his government, who

had even begun making preparations for it. But there were no outward signs of danger and the people of Richmond had their judgment clouded by their faith in General Lee.

Now gloom seized the capital. A Confederate army officer, Captain Clement Sulivane, noted the change: “About 11:30 a.m. on Sunday, April 2d, a strange agitation was perceptible on the streets of Richmond, and within half an hour it was known on all sides that Lee’s lines had been broken below Petersburg; that he was in full retreat…and that the city was forthwith to be abandoned. A singular security had been felt by the citizens of Richmond, so the news fell like a bomb-shell in a peaceful camp, and dismay reigned supreme.”

Davis made his way from St. Paul’s to his office at the old customs house. He summoned the heads of the principal government departments—war, treasury, navy, post office, and state—to meet with him there at once. “I went to my office and assembled the heads of departments and bureaus, as far as they could be found on a day when all our offices were closed, and gave the needful instructions for our removal that night, simultaneously with General Lee’s withdrawal from Petersburg. The event was not unforeseen, and some preparation had been made for it, though, as it came sooner than was expected, there was yet much to be done.”

Davis assured his cabinet that the fall of Richmond would not signal the death of the Confederate States of America. He would not surrender. No, if Richmond was doomed, then the president, his cabinet, and the government would evacuate the city, travel south, and establish a new capital in Danville, Virginia, one hundred and forty miles to the southwest, and, for the moment, beyond the reach of Yankee armies. The war would go on. Davis told them to pack their most vital records, only those necessary for the continuity of the government, and send them to the railroad station.

The train would leave that night, and he expected all of them—Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, Attorney General George Davis,

Secretary of the Treasury George Trenholm, Postmaster John Reagan, and Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory—to be on that train. Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge would stay behind in Richmond to oversee the evacuation and then follow the cabinet to Danville. What they could not take, they must burn. Davis ordered that the train take on other cargo too, more valuable than the dozens of document-crammed trunks: the Confederate treasury, several million dollars in gold and silver coins, plus Confederate currency.

Davis spent most of the afternoon working at his office with his personal staff. His circle of talented and devoted aides included Francis R. Lubbock, a former governor of Texas; William Preston Johnston, son of the president’s old friend General Albert Sidney Johnston, who had been killed in 1862 at the battle of Shiloh; John Taylor Wood, U.S. Naval Academy graduate, who was Davis’s nephew by marriage and a grandson of Mexican War general and later president of the United States Zachary Taylor; and Micajah H. Clark, Davis’s chief clerk.

“My own papers,” recalled Davis, “were disposed as usual for convenient reference in the transaction of current affairs, and as soon as the principal officers had left me, the executive papers were arranged for removal. This occupied myself and staff until late in the afternoon.”

Davis then walked home to the presidential mansion at Twelfth and Clay streets to supervise the evacuation of the White House of the Confederacy. Worried citizens stopped him on his way: “By this time the report that Richmond was to be evacuated had spread through the town, and many who saw me walking toward my residence left their houses to inquire whether the report was true. Upon my admission…of the painful fact, qualified, however, by the expression of my hope that we would under better auspices again return, the ladies especially, with generous sympathy and patriotic impulse, responded, ‘If the success of the cause requires you to give up Richmond, we

are content.’ The affection and confidence of this noble people in the hour of disaster were more distressing to me than complaint and unjust censure would have been.”

When Davis arrived home, an eerie stillness possessed the mansion. His wife, Varina, and their four children were gone. He had foreseen this day. Hoping for the best but anticipating the worst, he had evacuated them from Richmond three days earlier, on Thursday, March 30. The president knew what could happen to civilians when cities fell to enemy armies. If Richmond fell, he wanted his family far removed from the scenes of that disaster.

Varina remembered their conversation before her departure: “He said for the future his headquarters must be in the field, and that our presence would only embarrass and grieve, instead of comforting him.” The president decided to send his family to safety in Charlotte, North Carolina, which was farther south than Danville. They would not travel alone. He assured Varina that his trusted private secretary, Colonel Burton Harrison, would escort and protect her during the journey.

Until the end, the first lady begged to stay with her husband in Richmond, come what may: “Very averse to flight, and unwilling at all times to leave him, I argued the question…and pleaded to be permitted to remain.” Davis said no—she and the children must go. “I have confidence in your capacity to take care of our babies,” he told her, “and understand your desire to assist and comfort me, but you can do this in but one way, and that is by going yourself and taking our children to a place of safety.”

Then the president spoke ominous words. “If I live,” Davis promised his beloved companion and confidante of more than twenty years, “you can come to me when the struggle is ended.”