Bloody Crimes (38 page)

But nothing untoward happened. The millions of Americans who had either viewed Lincoln’s corpse, participated in the huge processions, or watched the train pass by remained peaceful. Yes, the petty criminals who always prowl through urban crowds—especially the infamous pickpockets of New York City—preyed on some of the mourners. But the crowds did not beat or murder anyone they judged guilty of insulting the martyred Lincoln. Nor did they cry out for vengeance upon the sight of Lincoln’s corpse, or shout anti-Confederate epithets as the cortege rolled by.

Even the signs and banners spoke words of mourning, not ven

geance. Only a handful demanded justice—or revenge. Of all the public utterances, from the White House funeral in Washington to the graveside prayer in Springfield, and at all points between, only once did an overwrought orator surrender to an explicit impulse for vengeance. Instead, the bereaved millions adopted Lincoln’s second inaugural message of peace and reconciliation as their own.

From Springfield, General D. C. McCallum, the superintendent of the United States Military Railroad, who had ridden the rails all the way from Washington to ensure that everything went as planned, also reported to Stanton that he had accomplished his mission: “The duty assigned me has been completed promptly and safely, and I believe satisfactorily to all parties.”

Like Townsend, McCallum understated the meaning of what he had done. The journey of the Lincoln funeral train across America was a tour de force of railroad engineering and military planning. Without the railroads to move troops, rifles, artillery, ammunition, rations, horses, equipment, and other supplies over thousands of miles of standardized track, the Union might not have won the Civil War. Railroad technology had proven to be a key advantage over the Confederacy. Yes, the North might have prevailed in the end, but without railroads, victory would have taken longer, and at a price more dear in blood. Trains helped win the war, and now, at its end, one train, its progress followed by an entire people, helped bring the country together.

Lincoln was home, back at the Great Western Railroad station where his journey began four years earlier, on February 11, 1861, one day before his fifty-second birthday. When he left for Washington that morning, he contemplated that he might never return. He stood on the platform of the last car, looked at the faces of his neighbors, and spoke:

My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feelings of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a

quarter of a century, and have passed from a young man to an old one. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him who can go with me, and remain with you, and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To his care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.

Four years later, he had returned.

N

ot long after Lincoln’s remains reached Springfield, Jefferson Davis arrived in Washington, Georgia. His party had crossed the Savannah River very early in the morning, and while en route to Washington, they were informed that the federal cavalry was at that place, and they were looking for Davis. They stopped at a farmhouse and ate breakfast and fed their horses.

By this time, Davis’s escort was war weary and demoralized. They wanted to go home. John Reagan knew what else they wanted: “After they crossed the Savannah River and camped, and before reaching Washington, [Davis’s] cavalry, knowing that they were guarding money, demanded a portion of it.” If the government on wheels failed to pause here to pay them, they were going to seize the money. “[Breckinridge] told me that after he reached Washington the cavalry demanded that the silver and gold coin, equal to the amount of the silver bullion, should be divided among them, and that he and the officers commanding them found it necessary to yield or to risk their forcibly seizing it.”

It was here that Judah Benjamin decided to leave Davis and make

his own escape. The president’s pace was too leisurely for Benjamin’s taste, and he thought he would have a better chance on his own. He had never been comfortable riding a horse and set out in a carriage. Reagan spoke to him before he set off: “I inquired where he was going. ‘To the farthest place from the United States,’ he announced with emphasis, ‘if it takes me to the middle of China.’ He had his trunk in the carriage with his initials, J. P. B., plainly marked on it. I inquired whether that might not betray him. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘there is a Frenchman traveling in the Southern States who has the same initials, and I can speak broken English like a French-man.’”

Benjamin’s departure deprived Davis’s party of the good humor of its court jester in chief. It also suggested how Davis should travel from this point on—alone, or with no more than a couple of aides. Benjamin’s strategy served him well in the days ahead. His secretary of state gone, Davis mounted his horse and led the way to Washington, wary of reports of its occupation by the enemy. “We found no Federal cavalry at Washington,” recalled Reagan, “where we remained a few days. Before reaching that place, General Breckinridge and myself, recognizing the importance of the capture of the President, proposed to him that he put on soldier’s clothes, a wool hat and brogan shoes, and take one man with him and go to the coast of Florida, ship to Cuba, thence by an English vessel to the mouth of the Rio Grande. We proposed [he] take what troops we still had, to go west, crossing the Chattahoochee between Chattanooga and Atlanta, and the Mississippi River, and to meet him in Texas. His reply to our suggestion was: ‘I shall not leave Confederate soil while a Confederate regiment is on it.’”

Davis had been willing to abandon Richmond—and its citizens—for the good of the Confederacy, but what he told Reagan was not sound military strategy. If he hoped to avoid capture, his advisers were right. He needed to move fast to the Mississippi River or Florida.

When Davis trotted his horse into Washington, Georgia, late on

the morning of May 3, accompanied by an advance party of about forty men, the people welcomed their president as if he rode at the head of a triumphant army. Fate had spared this town during the war, and the citizens, unlike many in neighboring North Carolina, had not turned against the Confederacy. Eliza Andrews described the scene:

About noon the town was thrown into the wildest excitement by the arrival of President Davis. He is traveling with a large escort of cavalry, a very imprudent thing for a man in his position to do, especially now that Johnston has surrendered, and the fact that they are all going in the same direction as their homes is the only thing that keeps them together. He rode into town at the head of his escort…and as he was passing by the bank…several…gentlemen were sitting on the front porch, and the instant they recognized him they took off their hats and received him with every mark of respect due the president of a brave people. When he reined in his horse, all the staff who were present advanced to hold the reins and assist him to dismount.

A rumor spread that Yankees in pursuit of Davis were advancing on the town from two directions, but there was nothing to it. Another wild rumor spread through town that Davis was there. Once “the president’s arrival had become generally known,” Eliza wrote with pride, “people began flocking to see him.” This was the warm welcome that Greensboro and Charlotte, North Carolina, had withheld from Davis. In Georgia, the people’s delight at his presence improved his morale.

Davis received a dispatch from Secretary of War Breckinridge reminding him of their conversation the previous night in Abbeville, urging him to flee, and reporting on the military situation. There were almost no Confederate soldiers in the vicinity to protect Davis: “The troops are on the west side of the Savanah, and guard the bridge,” Breckinridge wrote. “A pickett which left Cokesbury after dark last

evening reports no enemy at that point. I have directed scouts on the various roads this side of the river. The condition of the troops is represented as a little better, but by no means satisfactory. They cannot be relied upon as a permanent military force. Please let me know where you are.”

Varina also sent a letter telling him to not make a stand, to leave his escort, and to flee.

I

n Springfield, the honor guard removed Lincoln’s body from the train, escorted it to the State House, where he had served as a legislator, given his famous “House Divided” speech, and, in another part of the building, set up an office after his election as president. His guards laid the coffin on a catafalque in the Hall of Representatives. Springfield was not a great American city, and its officials knew they could not hope to rival the pageantry displayed in Washington, Philadelphia, New York City, or Chicago. Nor could Springfield match the stupendous crowds or financial resources marshaled by the major cities. Indeed, Lincoln’s hometown had to borrow a hearse from St. Louis. However, what the state capital could not offer in splendor, it vowed to lavish in an emotional catharsis that would outdo every other city in the nation.

Few in Springfield were disappointed that Mary Lincoln was not on that train, even if it meant no Lincolns had made the trip from Washington. This morning, for the first time since the funeral train left Washington, the honor guard also removed Willie’s coffin from the presidential car.

The embalmer Charles Brown and undertaker Frank Sands opened Lincoln’s coffin. He had been dead for eighteen days, and his corpse had not been refrigerated. Only preservative chemicals and makeup had kept him presentable during the journey. At the beginning, at the White House funeral, Lincoln’s face looked almost natural. He changed along the way. People had started to notice it as early

as New York City. The face continued to darken, making necessary several reapplications of face powder during the trip. Travel dust and dirt had settled on the corpse during each open-coffin viewing, and the body men had to dust his face and black coat faithfully. Lincoln no longer resembled a sleeping man. Now he looked like a ghastly, pale, waxlike effigy.

The doors to the State House opened to the public at 10:00

A.M.

on May 3 and stayed that way for twenty-four hours. It was the first round-the-clock viewing of the entire funeral pageant. Mourners ascended the winding staircase to the Representatives’ Hall, approached the corpse from Lincoln’s left, walked around his head, and then departed down the same stairs. During the night, trains continued to arrive in Springfield, and people without lodgings wandered the streets until dawn.

By 10:00

A.M.

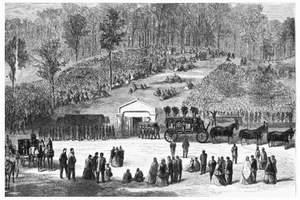

on May 4, seventy-five thousand people had passed by the presidential body. The coffin was removed from the capitol and placed in the hearse waiting on Washington Street. The procession began at 11:30

A.M.,

passing by Lincoln’s home at Eighth and Jackson streets, then heading west to Fourth Street, and down Fourth to Oak Ridge Cemetery, about a mile and a half from town. Oak Ridge was not a traditional urban cemetery with tightly spaced headstones lined up in rows. Instead, it was a product of the rural cemetery movement that had swept America, which had transformed old-fashioned graveyards into nature preserves with brooks, sloping valleys, oak trees, and tombs situated in sympathy with the natural landscape.

Lincoln’s guards removed his coffin from the hearse, carried it into the limestone tomb, and laid it on a marble slab. Willie’s coffin rested near him.

Bishop Matthew Simpson, who had officiated at the White House funeral, delivered the last oration at Oak Ridge Cemetery. “Though three weeks have passed,” he reminded his listeners, and “the nation has scarcely breathed easily yet. A mournful silence is abroad upon

THE SPRINGFIELD TOMB.

the land.” Simpson then set the unprecedented pageant in historical context: “Far more eyes have gazed upon the face of the departed than ever looked upon the face of any other departed man. More eyes have looked upon the procession for sixteen hundred miles or more, by night and day, by sunlight, dawn, twilight and by torchlight, than ever before watched the progress of a procession.” It was the end of an era, he said: “The deepest affections of our hearts gather around some human form, in which are incarnated the living thoughts and ideas of the passing age.”

Simpson read Lincoln’s second inaugural speech at tomb-side. Invoking the president’s mantra of “Malice toward none,” Simpson proposed forgiveness for the “deluded masses” of the Southern people: “We will take them to our hearts.” And we must, said Simpson, continue Lincoln’s work: “Standing, as we do today, by his coffin and his sepulcher, let us resolve to carry forward the work which he so nobly begun.”

But the bishop scorned Jefferson Davis and other Confederate leaders: