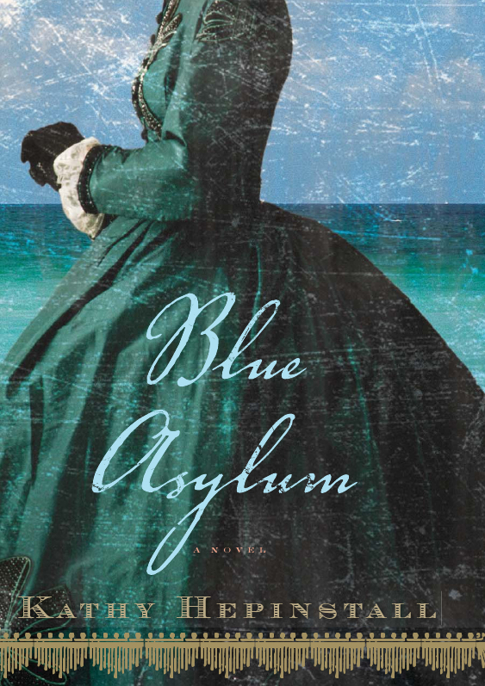

Blue Asylum

Copyright © 2012 by Kathy Hepinstall

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hepinstall, Kathy. Blue asylum : a novel / Kathy Hepinstall. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-547-71207-9 (hardback) 1. Plantation owners’ spouses—Virginia—Fiction. 2. Psychiatric hospital patients—Fiction. 3. Asylums—Fiction. 4. Virginia— History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Fiction. I. Title. PS3558.E577B58 2012 813'.54—dc22 2011029653

Book design by Brian Moore

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Keith

When Iris dreamed of that morning, the taste of blood was gone, and so was the odor of gun smoke, but her other senses stayed alive. The voices around her distinct. The heel of a bare foot between her ribs. The pressure of the pile of bodies on her chest. Was this what the others had felt too, as they died around her? Her dream followed the reality so well that when the bodies were yanked away from her, one by one, the weight released and the darkness cleared, and she jerked upright, gasping, on the floor of a jail cell in Fort Lane. She’d been given a blanket and nothing else, not even a pillow, for she had been judged insane even before the trial began, and her jailers followed the logic that the mad shunned the comforts of the rational. When she awoke on the floor, on that cold blanket, she thought first of the man who had murdered those innocent people by the barely crawling light of dawn, but her rage held down something deeper, something that searched for oxygen to speak.

Her trial lasted less than an hour. The judge didn’t want to hear her story. None of it mattered: The wayward turkeys that ran into the woods. The porcelain tub full of bloody water. The pale, blue-eyed baby. The two small graves. Her fate had already been decided. She was convicted and sentenced and put on a train to Savannah with an armed guard, from there sent on a series of trains going west, and when the tracks ran out she was taken by open-air coach to the port at Punta Rassa.

On the last leg of her journey, she set sail for Sanibel Island on the

Scottish Chief,

which also carried a hundred head of cattle. She had been allowed to bathe and put on a traveling dress with ornamental braids and her best spoon bonnet. She had even been allowed to bring her best clothes with her in a steamer trunk. But she had not been allowed to tell the story that would have excused or at least explained her actions.

The ship was stifling hot. The scent of the cattle rose up from the hull below her, their excrement and fear. She smoothed her hair and tried to steady her breathing. She looked out to the calm flat sea and tried to be just as calm and flat herself, so that others could see there had been a mistake.

This feeling of hatred for her husband, Robert Dunleavy, had to be contained. The judge had seen it, and it had influenced him. Frightened him, even. Wives were not supposed to hate their husbands. It was not in the proper order of things. And so she worked on this too, buried the hatred, for now, in an area of Virginia swampland where the groundwater was red.

The lows of restless cattle came up through the floorboards. They would go on to Havana, where they would be slaughtered.

“How much longer?” she asked the guard.

“Not long.”

The ship churned slowly through the water. A large bird dived at the surface and came back up with a struggling fish. She nodded, her lids closing, and took refuge in a gray-blue sleep.

She awakened as the ship was docking.

“We’re here,” said the guard.

She stood and he bound her hands in front of her with a silk scarf.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Regulations.”

He took her wrist gently and led her out to the gangplank, where she paused, amazed at the sight. Beautiful white sand beaches stretched into the distance. Palmettos grew on the vegetation line, and a sprawl of morning glories lay, still open, on the dunes. Coconut palms flanked the perimeter of the building itself, a huge two-story revival with Doric columns and tiered wings that jutted out on either side. A courtyard had been landscaped with straight columns of Spanish dagger. On the building, a sign:

SANIBEL ASYLUM FOR LUNATICS

A judge had signed the order. A doctor had taken her pulse and looked into her eyes and asked her a series of questions and confirmed that yes, something in her mind was loose and ornery, like a moth that breaks away from the light and hides instead in the darkness of a collar box. The heat made her shudder. Her dress was wet in the back. She moved her eyes away from the sign and noticed a blond boy and a large Negro man fishing in the surf. Both of them stared at her. The man was so black he made the pale boy beside him look like a ghost. The boy kept touching something on his cheek.

“Time to head in, ma’am,” the guard said, and for just a moment she thought of hurling herself into the water and letting the folds of her traveling dress pull her down to the bottom. She shook off the thought, steeled herself, and gingerly made her way forward, difficult as it was to balance with her hands tied in front of her.

The blond boy, whose name was Wendell, had been fishing for snook with the chef, a freed Negro from Georgia, who was using his prized snakewood baitcaster. The chef was fishing and talking, fishing and talking, fishing and talking, a rhythm he had perfected through the years. His topic of conversation, on this morning, was his castor bean garden—his latest attempt at growing wealthy overnight—and he would have succeeded already if a rare frost hadn’t killed the plants this past winter. Federal prisoners in Tortuga were dropping dead left and right from yellow fever. The treatment: castor oil. His new batch of castor beans was hardy, and although they covered just a half-acre at present, he had plans for expansion.

Overhead, a brown pelican circled.

“Of course I don’t wish yellow fever on any man,” the chef said.

Wendell wasn’t listening. He’d just caught a glimpse of the ship. “It’s a side-wheeler,” he announced.

The chef pressed his lips together, annoyed by the interruption. He followed Wendell’s gaze. “

Scottish Chief.

That’s Summerlin and McKay’s ship. It’s probably taking more cattle to the Bahamas.”

The side-wheeler steamer approached the dock.

“Why is it stopping here?” Wendell asked.

“I heard we got a new one.”

“Oh?” Wendell cocked his head slightly to one side, his way of showing intrigue. “Maybe it’s a really crazy one.” Those were Wendell’s favorites; lunatics were captivating, and the crazier the better. He had lived around them all his life, because his father was the superintendent and chief psychiatrist of the asylum. Wendell believed he was crazy himself, and it was only a matter of time before it was discovered in him and he was locked away with the others. He watched the boat, his eyes wide and drying out in the sea air. The end of his cane pole dipped downward.

“Look, boy,” said the chef. “You got one!”

The pole jerked and danced in Wendell’s hands. He pulled back too hard. A weighted hook, still with half the bait on, came flying and landed in Wendell’s cheek. He sucked in his breath as the hook stuck fast, the fishing line trailing off into the wind. Blood ran down in a trickle from the new puncture. He was hooked good now, good as any fish.

“You did it again,” the chef muttered, shaking his head as he cut the line to free him. “Third time this year. You must have a magnet in your head somewhere. Go in and find someone to cut that hook out of you.”

Wendell wasn’t listening. His head was cocked again. The fishhook dangled from his cheek. A woman had appeared on the gangplank. Slender and pale, chestnut-colored hair gathered in a chignon. Properly attired in a dress and white gloves. A single white feather adorned her bonnet. Her hands were tied in front of her.

“She looks just like any other person,” Wendell said.

“Lunatics have a way of blending in, like green snakes in the grass. Go on in, now. Your blood is scaring off the fish.”

“She can’t be crazy!” Wendell insisted.

She seemed to hear him, turning her head toward him, staring at him a long moment. He froze. The trickle of blood slowed and dried in a new breeze.

“You best stay away from the patients,” the chef said. “Remember what happened before, with Miss Penelope.”

The hook had stung a bit, but the name hurt him deeper. The chef’s baritone had evoked it without warning. The name had a barb on it, too. Instantly he remembered Penelope’s freckled skin, her long red hair, which she refused to tie back, her crystal-blue eyes and perpetual half-smile, the doll in a pinafore dress she carried around with her. His father was not inclined to tell him anything about the patients and had instructed the nurses and guards to be equally reticent around the boy. So Wendell gleaned information by eavesdropping on fragments of conversation. Penelope was from New England and suffered from a sadness of indeterminate origin that had evidently driven her, one night, to attempt to hang herself with the sash of her nightgown. After the finest doctors in Boston had failed to conceive of a cure, her family had sent her to the island in the desperate belief that sunlight and the fragrance of tropical flowers could restore some kind of radiance to her sad, addled brain. She was seventeen years old, and had God not killed her, she could have grown to be an old woman, and Wendell an old man, so old that the gap in their ages would mean nothing.

Wendell looked back at the woman on the gangplank. He stroked the hook in his cheek until another bead of blood appeared and ran down to his chin. He wiped off the gore, looked at it.

Penelope.

The name still hurt him. No one had cut it out of him yet.

Iris stepped off the gangplank and onto dry sand, the short heels of her leather boots crunching in it. Above her, white birds circled, shrieking down at her. A tear slid down her cheek before she could stop it. Annoyed, she bent her head and shrugged her shoulder to wipe the tear away. As she approached the courtyard she saw what wasn’t visible from a distance. The windows had bars on them.

A dozen people milled about the courtyard, guarded by attendants in white uniforms. One young man sat alone at a small round table set up near the steps. He had high cheekbones and was dressed in army-issued pants, a white shirt, and a thin coat. He wore a slouch hat. A checkerboard sat in front of him, set for a game. He looked up as she approached him. Something about his gaze was comforting. He glanced at her bound hands and nodded, as though remembering his own hands had once been tied that way. The man did not seem insane. Only deeply sorrowful. And if sorrow were a diagnosable offense, perhaps she was mad after all.

The man at the checkers table, Ambrose Weller, had watched the new patient come down the gangplank and make her way through the sand. He could tell she was a stranger to the coast, some genteel woman from further up South, completely out of her element. The way she moved, so dignified and calm, as though on a Sunday walkabout, reminded him of graceful sea birds he had seen after a storm, washed up on the beach, wings broken, wounded, and yet still attempting the gait characteristic of their species.

He had arrived on the island screaming and cursing, four strong men restraining him. He had to be carried all the way to his room and tied to his bed, dosed with laudanum until the visions faded into the sweet syrup of delirious forgetfulness, and his mind finally let go of its torments in the same reluctant way a child surrenders his playmates to the call of his mother.

He thought about the woman, remembering a time when he could, clearheaded, desire one. Then some bolt of memory reminded him that nothing was the same anymore. Dr. Cowell, the psychiatrist, had told him that the secret was not so much in forgetting as in distracting oneself. Think of the color blue, the doctor had suggested. Blue, nothing else. Blue ink spilling on a page. A blue sheet flapping on a clothesline. Blue of blueberries. Of water. Of a vase a feather a shell a morning glory a splash on the wing of a pileated woodpecker. Blue that knows nothing, blue of blank recollection, blue of a baby’s eyes, a raindrop in a spider’s web, a vein that runs from hand to wrist, the moon in scattered light, the best part of a dream and the sky, the sky, the sky . . .