Blue Skies

BLUE

SKIES

PRAISE FOR

BLUE SKIES

âEnlivened by wit and a knack for the stunningly vivid turn of phraseâ¦What makes

Blue Skies

a joy to read is the energy and colour of the writing, a meticulousâand very funnyâ gift for dialogueâ¦a marvellous economy of words.'

The Times

âA remarkably original Australian writerâ¦wickedly funny. Helen Hodgman has a sharp eye for detail and an even sharper ear for dialogue.'

Sunday Times

âThe considerable strength of this book is in its precise yet undramatic style.'

Spectator

âA first novel by a writer to watch, a penetrating tragi-comedy.'

Observer

âThe debut of a marvellously intractable writer.'

Sunday Telegraph

UK

âBlacker-than-black humourâ¦[a] gifted first novel.'

Guardian

âEntirely believable and deeply felt.'

New York Times

âVery good indeedâ¦funny, quirky.'

Glasgow Herald

âThoroughly entertaining.'

Irish Times

âA born writer with a style and an élan which are all her own.'

Auberon Waugh

âThe vacuous expanses of placid, pointless marriage are well drawnâ¦and the rising sense of crack-up firm but not over-emphatic.'

Julian Barnes

âA strange and memorable novel, rich in short circuits, cross currents, half themes. A potent voice, then and now.'

Eva Hornung

âHelen Hodgman's sharp details of the everyday, infused as they are with weird hallucination, distil the very essence of Tasmanian gothic.'

Carmel Bird

âA memorable novelâsensuous, strange, prickly as a sea urchin.'

Nicholas Shakespeare

âIslands produce artists whose vision is idiosyncratic, perhaps even kinked: Helen Hodgman's novel unsettlingly sums up the oddity and the bereft beauty of Tasmania back in the days before it filled up with boutique hotels and environmental activists. Gothic fiction usually requires bad weather, but Hodgman finds menace in the punishing glare of blue skies. Although the plot of her book suggests the early Ian McEwan and her hallucinatory style reminds me of David Lynch, these are affinities not influences: she is a genuine original. Like Virago before it, Text has rediscovered a small and scarily unforgettable classic.'

Peter Conrad

HELEN HODGMAN is the author of the novels

Blue Skies

(1976),

Jack and Jill

(1978; winner of the Somerset Maugham Award),

Broken Words

(1988; winner of the Christina Stead Prize),

Passing Remarks

(1996),

Waiting for Matindi

(1998) and

The Bad Policeman

(2001).

DANIELLE WOOD is the author of

The Alphabet of Light

and Dark

(2003; winner of the

Australian

/Vogel and Dobbie awards) and

Rosie Little's Cautionary Tales for Girls

(2006). She teaches at the University of Tasmania.

BLUE

SKIES

HELEN HODGMAN

Introduction by Danielle Wood

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Helen Hodgman 2011

Introduction copyright © Danielle Wood 2011

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Gerald Duckworth & Co., London, 1976.

Republished by Penguin Books, 1980.

Republished (with

Jack and Jill

) by Virago Press, 1989.

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company, 2011.

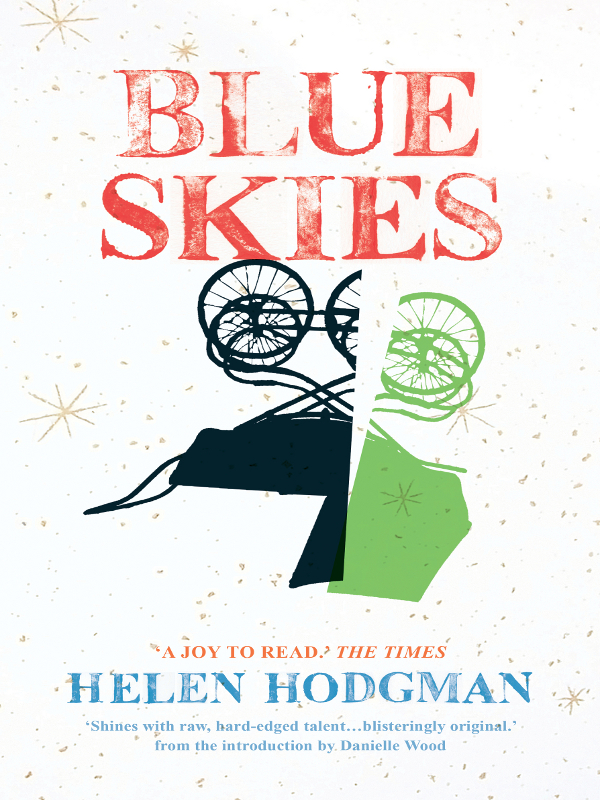

Cover art and design by WH Chong

Text design by Susan Miller

Typeset in Centaur by J&M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Hodgman, Helen.

Blue skies / Helen Hodgman.

9781921758133 (pbk.)

A823.3

For Joan Woodberry

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Harsh Light of Day

by Danielle Wood

Reading Group notes available at

textpublishing.com.au/resources/reading-group-guides

When I was seventeen, my grandfather bought me a plane ticket to London. For him, London not only had the strategic advantage of being far from the boyfriend I had at the time: it was also the most obvious destination for the cultural enlivenment of a girl born and raised in Hobart. I arrived there in early winter and, though I loved the city for its theatres and museums and crazy-angled street-corner buildings, I was topographically adrift. The Thames was not so much a river as a concreted canal, and I missed my mountain. Worse, I felt myself pressed down upon by the heavy lid of sky that lightened later, darkened earlier and showed its blueness less often than even the very worst of the winter skies I'd lived beneath in Tasmania. I experienced several weeks of unbroken greyness before the clouds peeled away to reveal that, higher up, the sky was blue after all. Over-excited with relief, I took its photograph.

Back in Hobart, I had my photographs developed. I expected to have a blue rectangle, a slice of pure cobalt to commemorate the day the sky cleared in London. But my picture turned out to be pale blue at best, and unmistakably shot through with greyish tendrils of cloud. Perhaps my eyes played tricks on me, or my cheap pocket camera was never up to the task of capturing that sky, that day. Or perhaps blue skies are not as uncomplicated as they first seem.

Helen Hodgman made the same journey in reverse. She was thirteen-year-old Helen Willes when she emigrated with her parents from Essex to Tasmania in 1958, as part of the âBring out a Briton' campaign launched by the Australian government. It was like stepping from black and white to colour. She remembers the sensory onslaught of the light, the vivid palette of nature and a perception that she had arrived in a world of greater social freedoms.

Social freedoms can be deceptive. Helen left Hobart High at fifteen and had a series of jobs, from a âdisastrous' stint at the Commonwealth Bank to waitressing, to working at a bookshop, where she finally started her education and met her future husband, Roger Hodgman. Their daughter, Meredith, was born in 1965. In 1969, Helen and a partner, Paul Schnieder, opened the Salamanca Place Gallery, the establishment that began the transformation of Hobart's signature row of historic waterfront warehouses into a hub for the arts.

In those years, in this place, Helen Hodgman was an observer twice removed. Not only was she from else where: she was a writer, though yet to write a word, and she turned this twin X-ray vision on her surroundings. What she saw was a landscape of beauty and mystery, and the cracking veneer of an insecure, insular society desperately trying to make nice in the aftermath of the violent dispossession wrought by colonisation.

It took Helen's return to England, when she moved to London in 1971, for these technicolour impressions to find their way onto the page.

Blue Skies

took shape during six intense months in 1975. The title and its understated irony came early, born of her experience that a blue sky can oppress just as certainly as can a grey one.

It is common for Tasmanian literature to be soft-lit with the kinds of autumnal colours that are so flattering to sandstone convict ruins, a contrast to the red dust and white gums of much mainland Australian writing. Helen turns up the intensity, creating a glare under which she examines human desperation and ugliness. It is usual, in writing about Tasmania, for dawns and dusks to proliferate. Instead, Helen gives us broad daylightâprecisely, a never-ending three o'clock. The unnamed heroine is, in this painfully deft portrait, suffering the crushing boredom and depression that can shadow the early days of motherhood. She is a curiously passive protagonist who is, as Helen describes it, âvery good at slipping sideways'. Fleeing the demands of her new baby, and the emptiness of her home and marriage, this young mother ricochets between the embraces of various and equally revolting lovers, flouting the social conventions of âTiny Town', all the while pursued by angry ghosts in the landscape.