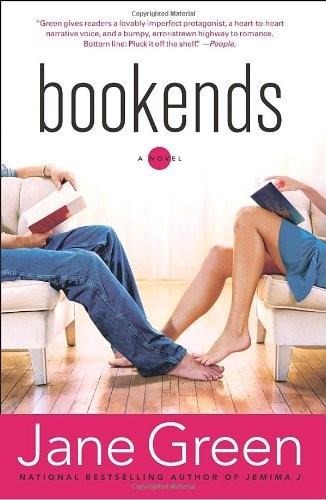

Bookends

PENGUIN BOOKS

BOOKENDS

Praise for Jane Green’s

Spellbound

‘If you’re new to the genius of Ms Green, we can exclusively reveal that she is amazing. With a capital A’

Heat

‘Green whips up a sparkling morality tale that points the finger at bad boys and low-rent romance’

Independent

‘Happy and melancholic… this beautifully written novel from the author of

Babyville

explores the effects of a husband’s repeated infidelity’

She

‘A compulsive read, with women you can’t help rooting for’

New Woman

‘A deftly humorous and insightful take on modern marriage’

Cosmopolitan

‘An engaging, grown-up read’

Company

‘An emotional rollercoaster of a read’

OK!

‘A warm and enjoyable read that brims with energy and a sense of fun’

Woman & Home

‘A sexy, romantic read’

Waterstone’s Books Quarterly

‘Guaranteed to gratify those with even the most voracious of appetites for feel-good fiction’

Jewish Chronicle

Praise for Jane Green’s earlier bestsellers:

‘Green writes with acerbic wit about the law of the dating jungle, and its obsession with image, and the novel’s as comforting as a bacon sandwich’

Sunday Express

‘A brilliantly funny novel about something close to every woman’s heart – her stomach’

Woman’s Own

‘Any woman who’s suffered a relationship trauma will die for this book… wickedly funny… it may not improve your life but it will make you squeal with laughter’

Cosmopolitan

‘Spot on… Once you pick up

Babyville

, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to put it down’

Mirror

‘An emotional and humorous novel’

Telegraph

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jane Green lives in Connecticut and London with her husband and four children. She is the author of

Straight Talking, Jemima J, Mr Maybe, Bookends, Babyville

and

Spellbound

.

Bookends

JANE GREEN

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published 2000

42

Copyright © Jane Green, 2000

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-190316-3

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for their support, kindness and help: Dr Patrick French at the Mortimer Market Centre; Adam Wilkinson at Body Positive; Marek, Jessica and all at the Primrose Hill Bookshop; James Phillips and Andrew Benbow at Books Etc. in Whiteleys; Laurent Burel; Yasmin Rahaman; Tricia Anker.

My ‘inner circle’: Annie, Giselle, Caroline and Julian, and finally David, for everything.

Chapter one

The first time I met Josh, I thought he was a nice guy but a transient friend. The first time I met Si I fell hopelessly in love and prayed I’d somehow be able to convert him.

But the first time I met Portia I thought I’d found my soulmate.

She was the sister I’d always longed for, the best friend I’d always wished I had, and I truly and honestly thought that, no matter what happened with our lives, we would stay friends for ever.

For ever feels a long time when you’re eighteen. When you’re away from home for the first time in your life, when you forge instant friendships that are so strong they are destined, surely, to be with you until the bitter end.

I met Josh right at the beginning, just a few weeks after the Freshers’ Ball. I’d seen him in the Students’ Union, propping up the bar after a rugby game, looking for all the world like the archetypal upper-class rugger bugger twit, away from home with too much money and too much arrogance.

He – naturally – started chatting up Portia, alcohol giving him a confidence he lacked when sober (although I didn’t know that at the time), and despite the rebuffs he kept going until his friends dragged him away to find easier prey.

I’m sure we would all have left it at that, but I bumped into him the next day, in the library, and he recognized me instantly and apologized for embarrassing us; and gradually we started to see him more and more, until he’d firmly established himself as one of the gang.

I’d already met Si by then, had already fallen in love with his cheeky smile and extravagant gestures. I was helping out one of the girls on my course who was auditioning for a production of

Cabaret

. It was my job to collect names and send them into the rehearsal hall for the audition.

Si was the only person who turned up in full costume. As Sally Bowles. In fishnet stockings, bowler hat and full make-up, he didn’t bat an eyelid as the others slouched down in their hard, wooden chairs, staring, jealous as hell of his initiative. And his legs.

He went in, bold as brass, and proceeded to give the worst possible rendition of

Cabaret

that I’ve ever heard, but with such brazen confidence you could almost forgive him for being entirely tone-deaf.

Everybody went crazy when he’d finished. They went crazy because he so obviously loved,

loved

, being centre stage. None of us had ever seen such enthusiasm, but even though Si knew every song, word for word, he had to be content with camping it up as the narrator, as Helen, the director, said she never wanted to hear him sing again.

Eddie was a friend of Josh. A sweet gentle boy from Leeds who should probably have been overwhelmed by our combined personalities, but somehow wasn’t. He was easy company, and always willing to do anything for anybody he cared about, which was mostly us, at the time.

And then of course there was Portia. So close that our names became intertwined: Catherine and Portia. Two for the price of one.

I met Portia on my very first day at university. We were sitting in the halls of residence common room, waiting for a talk to begin, all sizing each other up, all wondering whom to befriend, who seemed like our

type

, when this stunningly elegant girl strode in on long, long, legs, crunching an apple and looking like she didn’t have a care in the world.

Portia, with her mane of dark auburn hair that reached down between her shoulderblades. Portia, with her cool green eyes and dirty laugh. Portia, who looked like she should have been a class-A bitch, but was, then, the greatest friend I’d ever had.

Her confidence took my breath away, and, when she flung her bag down on the floor and sank into the empty chair next to mine, I prayed she’d be my friend. She stretched out, showing off buttersoft suede thigh-high boots, exactly the boots I’d dreamt of wearing if I ever got thin enough, and, taking a last bite of the apple, tossed it with an expert flick of the wrist into the dustbin on the other side of the room.

‘Yesss!’ she hissed triumphantly, her cut-glass accent slicing through the room. ‘I

knew

all those years as goal shooter would pay off sometime,’ and then she turned to me. ‘I’m Portia. When does this bloody thing start?’

Portia had more than enough confidence for both of us. We found, within minutes, that despite our different backgrounds we had the same vicious sense of humour, the same slightly ironic take on life, although it took a few years for the cynicism to set in.

We made each other laugh from the outset, and there never seemed to be a shortage of conversation with Portia. She had a prime room – one of the most coveted in the building. A large bay window overlooked the main residential street, and Portia repositioned the armchairs so that they were in the bay, draping them with jewel-coloured crushed velvet throws. She sat there for hours at a time, watching people go by.

Most of the time I’d be there too. The net curtains would be rolled around the string of elastic from which they hung, and in summer the window would be open and we’d sit drinking bottles of Beck’s, Marlboro Lights dripping coolly from our fingers, waiting for the men of our dreams to walk past and fall head over heels in love with us.

They frequently did. With Portia, at any rate.

Even then she had more style than anyone I’d ever met. She would go to the hippy shops in town and pick up brightly coloured beaded dresses for a fiver, tiny mirrors sprinkled all over them, and the next day I’d find her finishing off two stunning new cushions, the mirrors glinting with ethnic charm.

She did have money, that much was obvious, but there was never anything snobbish or snooty about Portia. She’d been brought up in the country, in Gloucestershire, in a Jacobean manor house that could probably have provided accommodation for most of our campus.

Her mother was terribly beautiful, she said, and an alcoholic, but, Portia sighed, who could blame her when her father was sleeping with half of London. They had a pied-à-terre in Belgravia, to which Portia eventually decamped when she refused to go back to boarding school, opting to do her A-levels in a trendy tutorial college in London instead.

It was a world away from my own background. I was intimidated, impressed, and in awe of her life, her lifestyle. My life had started in deepest, darkest suburbia, in an ordinary pre-war semi on a main road in North London. My father, unlike Portia’s landowning, gambling, semi-aristocratic parents, is an accountant in a local firm. My mother is a housewife who works occasionally as a dinner lady in the local primary school.

As far back as I can remember I would escape from my humdrum world by burying myself in books – the one true love of my life when growing up.

I love Mum and Dad. Of course. They are my parents. But the day I went to university I realized that they had nothing to do with me any more, nothing to do with my life, with who I wanted to be, and never was I more aware of cutting the umbilical cord than when I met Portia.

I used to wonder whether style was something you were born with, or whether it was something you could buy. I’m sure that it’s something you’re born with, and Portia was just fortunate in being able to afford the very best as well. I still have no doubt, however, that she could have made a bin bag look sophisticated. The rest of us would shop at Next, but she always looked like she was wearing Yves Saint Laurent. She’d joke about it, about our sweaters covered in holes, and our faded old Levis, the more rips and holes in them the better. She’d laugh about how she found it physically impossible to walk in anything with less than three-inch heels due to a birth defect. She’d sink to her knees and grab the bottom of my favourite sweater – a sludge-green crocheted number that, with hindsight, was pretty damn revolting – begging, pleading, offering me bribes to burn the sweater and have her N. Peal cashmere sweater instead.

There were a few people who were jealous of her. There always are. I remember one night when Portia was cornered by some big rugby bloke in a pub. She politely declined his offer of a shag, to which he responded by screaming obscenities at her and telling her she was a rich bitch and the most hated girl at university. He made some references to her being a Daddy’s girl, and then said she was the university joke. Eventually, when she recovered from the shock, she slapped him as hard as she could and ran out to the garden of the pub.

I found her there. I hadn’t known what was going on. I’d been in the other room, chatting to people, and it was only when I noticed Portia hadn’t come back that I went looking for her.

She was curled up in, a heap at the bottom of the garden. It was raining and she was soaking wet, her hand covered in blood, her skin torn through to the bone. She was sobbing quietly, and I took her in my arms. After a while I insisted she go to hospital for stitches. Even there she refused to say what had happened, and the next day the rumours flew that he, the rugby oik, had hit her, had pushed her down the stairs. She never said anything about the incident, neither confirmed nor denied, thereby making the rugby bloke into something of a pariah with women.

Months later we were sitting in a café on the high street, when Portia suddenly said, ‘Do you remember that night? The night of the bloody hand?’

I nodded, curious as to what she was going to say, because she’d never spoken about it before.

‘Did

you

think he’d hit me? Pushed me down the stairs?’

I shrugged. I didn’t know.

‘I did it myself,’ she said, lighting up a cigarette and examining the tiny scar on the knuckle of her right hand. ‘It’s this thing I do,’ she said nonchalantly, dragging on the cigarette and looking around the room as if to say that what she was telling me wasn’t important. ‘I have a tendency to hurt myself. Physically.’ She paused. ‘When I’m hurting inside.’ And then she called the waitress over and ordered another coffee. By the time the waitress had gone, Portia was on to something else and I couldn’t get back to the subject again.

It was the first indication I’d had that Portia wasn’t perfect. That there might be things in her past that weren’t perfect. It was only as I got to know her better that I realized the effect her parents had had on her.

It wasn’t that they

didn’t

care, she said. It was quite simply that they hadn’t been around enough

to

care. Her mother lay in bed all day, in an alcoholic haze, and her father disappeared to London, leaving Portia to fend for herself.

This cutting, this occasional self-mutilation when life became too hard, was clearly an act of desperation, of Portia screaming to be noticed, to be heard. But if you didn’t know, you wouldn’t know, if you know what I mean. She was funny, generous and kind. When she got fed up with my persistent moaning about my mop of dull mousy hair, she whisked me to the hairdressers and instructed them to do lowlights.

The girl at the hairdressers didn’t like Portia, didn’t like her imperious manner, but Portia’s mother went to Daniel Galvin, so Portia knew what she was talking about. When Portia said not the cap, the foil, they listened, and when she chose the colours of my lowlights, they listened. And when they finished, Portia showed them a photograph of a model in a magazine, and they cut my hair so that it fell softly around my face, feathery bits brushing my cheek. I had never felt beautiful before, only ever mildly attractive on a very good day, but for a few minutes, in that crappy local hairdressers surrounded by old dears with blue rinses, with Portia smiling just behind me, I felt beautiful.

Portia was the most sought-after girl at university. As the builders at the end of our road one summer used to say, ‘She’s got class.’ When I walked past they’d scream, ‘Cor, fancy a night out, love?’ To which I’d smile coyly and continue walking, faintly irritated by the interruption, but nevertheless flattered that they had even bothered to notice me.

When Portia walked past they’d fall silent. Downing their tools one by one, they’d step to the edge of the scaffold to watch her glide by, her face impassive, her eyes fixed on the middle distance. And once she’d passed they’d look at one another with regret, regret that she wouldn’t talk to them, regret that twelve feet up a collection of steel poles was the closest they’d ever get to a woman like Portia.

But the thing was that underneath, beneath the designer trappings and

soigné

exterior, Portia was just like me. We were both eternal romantics, although we hid it well, and both desperately needed to be loved.

Portia had been practically abandoned by her parents since birth, and, though my background wasn’t quite so dramatic, I was the product of people who should never have got married, of people who spent their lives arguing, shouting, who led me to believe, as a young child, that it was all my fault.

My parents were still together, very much so, but I suppose every family has its problems, and mine no less than anyone else. We just don’t talk about it. Everything is swept under the carpet and forgotten.

Perhaps that’s why I loved Portia so much. She was the first person I’d met with whom I felt able to be completely honest. Not immediately, but she was so warm and so open herself (years of therapy, she said) that it was impossible not to fill the silences after her stories with memories of my own.

We gradually allowed more people to enter into our world. Only a select few, only the people who shared our humour, but eventually, by the end of the year, we were a small group of misfits, all from completely different walks of life, but all somehow feeling as if we had found another family.

So there was Eddie, Joshua, Portia and Si. It never occurred to me that we didn’t have any close female friends, but with each other we never needed them. Sarah entered halfway through the second year, by virtue of going out with Eddie, but, although we made her feel welcome, she never really belonged.

I longed to bring someone into the group in the way that Eddie had brought Sarah. And I had my fair share of flings. Of going on drunken pub crawls and ending the evening in a strange bed with a stranger, waking up knowing that you weren’t going to see one another again, but praying that, nevertheless, you would. But they were only flings. The grand passion of which Portia and I talked, relentlessly, eluded me during those years, and one-night stands were the best I could get.