Books & Islands In Ojibwe Country (5 page)

Read Books & Islands In Ojibwe Country Online

Authors: Louise Erdrich

Massacre Island

It is not considered wise to point a finger at any island, especially this one. The Ojibwe use mouth or head to indicate direction, and are often humorously mocked for “pointing with the lips.” But it is impolite to point a finger at people, and the islands as well. Pointing at the islands is like challenging them. And you don't want to challenge anything this powerful.

Massacre Island is a forbidden place. Recently, two men who tried to fast there were bothered the entire night by ghosts. As we approach the island, I feel its brooding presence. I can't tell whether this island is a formidable

place because of its history, or whether it possesses a somber gravity all on its own. But the very look of the place disturbs me. Massacre Island is located where the lake deepens. Sounds travel farther, the air thins, the waves go flat. Its rocks sloping down to the water are not the pale pink flecked granite of the other islands, but a heavy gray nearly black in places and streaked with a fierce red-gold lichen.

On this island, the Ojibwe wiped out an entire party of Sioux, or Bwaanag. As Tobasonakwut tells it, the entire island was ringed by Ojibwe canoes. At a signal, the

sasawkwe,

the war whoop, a terrifying and a bloodthirsty shrill, was raised. From one canoe to the next, it traveled, a ring of horrifying sound. The canoes advanced four times. The sasawkwe was raised four times. On the last time, the Ojibwe paddlers surged all the way forward, beached their canoes, and stormed the Bwaanag. He shows where the warriors died, including one who staked himself into the earth and fought all comers who entered his circle, until he was overwhelmed.

Atisikan

The paint,

atisikan,

should be patented, says Tobasonakwut. It is an eternal paint. The Ojibwe Sharpee paint. It works on anything. When he was little he often watched the paint being prepared. It was used for other things, besides painting on rocks. For burial, for bringing people into the

religion, for teachings, for decorating request sticks and Mide stakes.

The recipes for paints used by other tribes are often based on vermillion from outcroppings of cinnabar. The Inuit used blood and charcoal. Burnt plum seeds and bull rushes were mixed into a black paint by the Klamath, and many tribes used blue carbonate of copper. Later, as we walk the Kaawiikwethawangag, the Eternal Sands, I will find some of the mysterious ingredients of the Ojibwe atisikan at my feet, then jumping from the lake.

Obabikon

On a great gray sweep of boulder, high above Obabikon channel, a rock painting gives instructions to the spirit on how to travel from this life into the next life. Such a journey takes four days and is filled with difficulties.

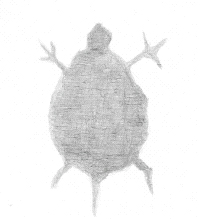

For that reason, loved ones provide the spirit with food, spirit dishes, and encouragement in the form of prayers and songs. We climb to the painting with tobacco and leave handfuls by the first painting, a line with four straight, sweeping branches, and the second painting, which is of a

mikinaak,

or turtle.

The mikinaak has immense significance in Ojibwe life. As there are thirteen plates in its back, it is associated with the thirteen moons in the yearly cycle, and also with women. It was women, says Tobasonakwut, who were responsible for beginning Ojibwe mathematical calculations. They began because they had to be concerned with their own cycles, had to count the days so that they would know when they would be fertile. They had to keep close track of the moon, and had to relate it to their bodies in order to predict the births of their children. And they had to be accurate, so that they could adequately prepare. In a harsh Ojibwe winter, giving birth in an unprotected spot could be lethal. Women had to prepare to be near relatives and other knowledgeable women. Mathematics wasn't abstract. It was intimate. Dividing and multiplying and factoring were concerns of the body, and of survival.

Whitefish Bay

To get into Whitefish Bay from where we are will require lots of sandwiches, water, a full gas tank, and two extra

five-gallon plastic gas containers that ride in front when full. We start early on a tremendously hot morning. By now, I'm much happier in a boat. I still have the usual fantasy, on starting out, involving the rock and the swim to shore towing Kiizhikok, but by now I'm used to it. I try to move on quickly and enjoy the breeze whipping with heroic freshness off the lake. Whitefish Bay connects to Lake of the Woods via a peculiar contraption called a boat trolley. This is a suspicious-looking, wood-ribbed basket that the boat is floated onto. By sheer muscle power, turning a big red metal wheel that moves the trolley basket along a set of metal tracks, the boat is painfully transferred. Once on the other side of the concrete channel, we reload ourselves and start off, into Whitefish Bay.

First, we pause at the place where Tobasonakwut was born, a quiet little bay of old-growth pine and soft duff. Just after he and his brother were born, Tobasonakwut's name was discovered by his father, who gazed out into the bay and saw a certain type of cloud cover, low and even. Tobasonakwut. His twin was named for a small bird that visited his mother shortly after the birth. She has told Tobasonakwut that as this is the type of bird who nests in the same place year after year, if he ever sees one on a visit it will be a relative of the one who named his brother.

As he is sitting beneath a tree that must have been a sapling when he was born, as he is singing to his

daughter, I realize that after thousands of years of continual habitation and birth on the shores of this lake, Tobasonakwut is one of the last human beings who will ever be born out on these islands.

Wiikenh

Wiikenh tea strengthens the immune system. Mixed with a mashed waterlily root,

okundamoh,

it draws out infection and poison. Speakers chew wiikenh to keep their throats clear, and singers chew it to strengthen their voices at the drum. As we enter a long channel filled with shallow water and small flooded bays, Tobasonakwut sees vast clumps of bright green-gold reeds and mutters, over and over, “So much wiikenh!” This is not the gloating sound I've heard before in his voice when discovering so much medicine. Rather, he is distressed that it should be sprouting in such tremendous abundance and no one else has come to pick it. His tone implies that this should all have been harvested, that the endless thick fringe of plants along the shores is an almost painful sight. One thing is sure, he can't pass it up, and for about an hour we putter along, stopping from time to time for him to lean over the prow of the boat and pull up the long tough bundles of muddy roots. He slices them off with a very sharp hunting knife while I sit behind the wheel of the boat with the baby.

Wiikenh gathering is very boring to her, but she has decided to be lulled into a state of contemplation by a combination of breast milk and boat engine. Indeed, every time she gets into the boat now, she tips her head dreamily toward my nipple. I've grown used to having her there. I've filmed eagles and those young moose, dancing loons and

zhegeg,

pelicans, with one hand while she nurses away. Indeed, though I haven't mentioned it, I have been filming everything I've described all along, as well as somehow brandishing a pen and notebook, all while nursing. One grows used to it.

Sometimes I look at men, at the way most of them move so freely in the world, without a baby attached, and it seems to me very strange. Sometimes it is enviable. Mostly, it is not. For at night, as she curls up or sprawls next to me and as I fall asleep, I hold onto her foot. This is as much for my comfort as to make sure that she doesn't fall off the bed. As I'm drifting away, I feel sorry for anyone else who is not falling asleep this way, holding onto her baby's foot. The world is calm and clear. I wish for nothing. I am not nervous about the future. Her toes curl around my fingers. I could even stop writing books.

Spirit Bay

The name on the map is actually Devil's Bay, so tiresome and so insulting. Squaw Rock. Devil's This and Devil's That. Indian or Tomahawk Anything. There's no use

railing. You know it as well as I do. Some day, when there is nothing more important to do, the Anishinaabeg will demand that all the names be changed. For it was obviously the rock painting at the entrance to the bay that inspired the name. It is not a devil, of course, but a spirit in communication with the unknowable. Another horned figure, only this time enormous, imposing, and much older than the one in Lake of the Woods.

This spirit figure, horns pointed, wavering, and with arms upraised, is fading to a yellow-gold stain in the rock. It is a huge figure, looming all the way up the nine- or ten-foot flat of the stone. At the base of this painting, there is a small ledge. Upon it, a white polo shirt has been carefully folded, an offering, as well as a pair of jeans. The offerings are made out of respect, for personal reasons, or to ask the spirit of the painting for help. There are three rolls of cloth, tied with ribbons. Asema. Again, here are the offerings, the signs that the rock paintings are alive and still respected by the Anishinaabeg.

Binessi

I get very excited when I see the thunderbird pictured on a cliff far above the water. It is so beautifully painted, so fluid and powerful even glimpsed from forty feet below. “Are you strong? Are you agile?” Tobasonakwut asks. “If you are you should climb up to that rock. You'll never be

sorry that you did.” I believe him. I grab my camera, my tobacco offering, and retie my running shoes. I already have my twenty extra pounds left over from having a baby. I am just pretending that I am strong and agile. Really, I'm soft and clumsy, but I want to see the painting. I am on fire to see it. I want to stand before that painting because I know that it is one of the most beautiful paintings I will have ever seen. Put up there out of reach or within difficult reach for that very reason. At that moment, I just want to see it because it is beautiful, not because I'll get some spiritual gift.

The climb is hard, though of course it looked easy from below. Like all women are accused of doing, I claw my way to the top. Sweaty, heart pounding, I finally know I'm there. All I have to do is inch forward and step around the edge of the cliff, but that's the thing. I have to step around one particular rock and it looks like there's nothing below it or on the other side. I could fall into the rocks. My children could be left motherless. Or I could simply get hurt, which is not simple at all. I calculate. The nearest hospital is hours away and there is that trolley contraption. So I don't go around the rock, but seek another route. I continue climbing until I'm over the top of the cliff. Still, I can't see down. I don't know how to get down to the paintings. Again, I nearly take the chance and lower myself over the cliff but I can't see how far I'd fall. Finally, looking far, far down at my baby in her tiny life jacket, I know I'm a mother and I just can't do it.

Climbing back into the boat is admitting defeat.

“Give me the camera, and tobacco,” says Tobasonakwut.

“No!” I say. “Don't do it!”

“Why? If you can't make it then you'll feel bad if I do?”

“Just like a guy, so competitive! Because you

will

go around the corner of that rock and you'll fall and kill yourself.”

“I will not fall. I've done this before.”

“How many years ago?”

“A few.”

With terse dignity, Tobasonakwut goes. He's an incredible climber and regularly shames the twenty-somethings who come to fast on the rock cliffs by climbing past them and even dragging up their gear. I know he'll make it. He'll do something ridiculous, maybe even get hurt, but he'll manage to get right next to the paintings.

He's always poking around in the islands. Once, he described a rockslide he started coming down from a cliff like this one. Remembering this, I maneuver the boat away from a skid of rocks on the south side of the cliff, though he didn't go up that route. Anyway, he had a terrifying ski down on the boulders and at the bottom one bounced high in the air, over him, and its point landed right between the first and second toe of his right foot. He said that he'd done something mildly offensive to the rocks. He'd thrown one down to see what happened. That's how the landslide started. When the boulder bounced down on his foot, he thought it would slice his foot off. But when he looked down his foot was still there.

Just a crushed place between his toes. It was as if, he said, the rocks, the grandfathers had said, “Don't fool around with us.”

And now he's climbing rocks again.

It's no use. The best I can do is make sure that the baby's comfortable. I might as well be comfortable too. I take a fat little peanut butter sandwich from the cooler and munch dreamily, while nursing, and after a while the wind in the pines and the chatter of birds lull us into a peaceful torpor. I forget to watch for him, forget the all important ascent. From somewhere, at some point, I hear him call but he doesn't sound in distress so I just let my mind float out onto the lake.