Boost Your Brain (22 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

Tips to Remember

On the one hand, it’s a blessing that your hippocampus handily decides for you which memories to keep and which to discard. Imagine if you remembered every little detail of every experience? You’d have no way to prioritize, no way to sift through all those memories and give them relevance.

Jill Price, who suffered from this rare condition and wrote the 2008 book

The Woman Who Can’t Forget,

told ABC News’s Diane Sawyer that the experience was like watching a split-screen TV, with the present on one side and memories of the past running continuously on the other. The overload of information left her feeling paralyzed and depressed.

Fortunately, the vast majority of people have no such problem. Their hippocampi work quite well, remembering consequential information and tossing away the rest. Of course, as impressive as it is, the hippocampus isn’t perfect. It may fail to flag something you later wish it had. Or send to storage something you’d rather forget.

The good news is that there are ways to influence the hippocampus into sending for storage—and reinforcing in your memory—those things you’d really like to keep.

Keep reading for some suggestions.

Make It Memorable

Your hippocampus will be more likely to send something for long-term storage if it’s, well, memorable. Making it so may require converting the information you hope to remember into something more likely to stick out in your mind.

So, what sticks out? Not names, random words, or numbers—that’s for certain. But images do, so converting less memorable forms into images is one way to elicit the “save” message. And not just any image, but one that stands out—by being sexy, funny, or absurd. It’s the equivalent of tricking that deer into thinking the squirrel is really a wolf.

Even better, give the images a story. By creating a story composed of vibrant, provocative images of the items you’re trying to remember, you’ll make it far more likely to be stored and more easily recalled. So, if you’re trying to remember your grocery list, instead of memorizing each item—pretzels, milk, napkins—you might imagine a giant comic-strip-style pretzel diving into a huge bucket of milk and drying off with a napkin. You’ve just tricked your hippocampus into saving random words it might otherwise have ignored.

Get Emotional

No, you don’t have to tear up every time you want to remember an acquaintance’s name, but since your brain is more likely to remember something that’s tied to an emotion, you can trick it into doing so by linking whatever you’re trying to remember with fear or excitement or some other emotion. What do I mean? Suppose you’re trying to remember that you have to drop a letter in the mailbox first thing in the morning. You could tell yourself,

Don’t forget to mail the letter!

But you’ll be more likely to “not forget” if you instead tell yourself that if you don’t mail the letter, you’ll fall off a cliff when you step out your front door. Imagine the scene as vividly as you can. Chances are, as you leave your house, that image will pop to mind, and so will the memory of what you need to do.

Group ’Em

Remembering long lists is no easy task. But you’d be surprised at how well you can do if you group items into sets of no more than four, a tactic that’s called “chunking.”

If you’re trying to remember the string of numbers 454699077777, you might think of it as 4546–9907–7777. Similarly, if you’re trying to remember a grocery list, group your buys in some memorable way, like where they are in the grocery store. So, eggs, napkins, paper towels, chicken, cheese, steak, milk, fish, and toilet paper becomes much more memorable as eggs, milk, cheese; napkins, paper towels, toilet paper; chicken, steak, fish.

Make an Association

We’ve all heard the suggestion that in order to remember someone’s name, we should associate it with a specific attribute. But it’s not enough to simply remember Bob as blue-shirt Bob. What if you come across him and he’s changed his attire? And what’s to distinguish him from other people in blue shirts?

A more effective strategy is to choose a facial or other unchanging feature and create a memorable image in your mind that incorporates the person’s name. For example, to remember Bob, you might note his rather short legs and imagine him bobbing up and down as he tries to reach something on a tall table. (If he’s tall, you might have to pick some other attribute or alter this one in some memorable way.)

The same trick can apply to other information you’re trying to remember. If you want to remember your cousin Harry’s birthday in late October, you might try to think of him as Halloween Harry and picture him dressed as a goblin and carrying a candy bag. You can also tie someone’s name to his or her profession, a trick I use when I meet people in social settings. Meeting Penny, a writer, I might think of a pen to remember her. Use your imagination. You’ll be surprised at what you come up with.

Make an Effort

This may sound obvious, but we’ve all lamented our inability to remember a name when, in fact, we really didn’t put much effort into giving it attention in the first place. Tell your hippocampus something is important—and worthy of memory—by repeating the information several times, writing it down, or in some other way making an effort to remember it. In the case of remembering someone’s name, ask the person to repeat it or even to spell it. Then say it back to him or her. With each repetition you’re sending a “save” signal to your brain.

Putting the Tips to Use: One Technique

In the late spring of 2012, I was invited to share the science behind brain fitness with the studio audience of cardiothoracic surgeon and television personality Dr. Mehmet Oz. This being TV, just having me

tell

the audience what I knew would be far too boring. Instead, I opted to show them. (You can watch this by going to my website, www.neurologyinstitute.com.)

Before the show, Dr. Oz’s production team randomly selected seven audience members to learn a few tools they could use in practicing feats of memory. We met in a comfortable conference room and got right to work.

There are a slew of highly effective memory techniques that range from the simple to the extremely complex, but since our goal—to remember a list of twenty words—was fairly easy, I chose one of the simplest. First, I picked up a marker and wrote on a whiteboard twenty random words, selected by the production team. Then the fun began.

We first “chunked” the list into groups of four. Then, together, we imagined a funny scene for each chunk and placed it, in our minds, behind the chair of a fellow group member. (This is a variation of the memory palace technique, which I had to adapt since the group of people had just met and didn’t have a common place they could all envision in their minds.) The first chunk—milk, egg, apple, hamburger meat—we placed behind the chair of Stacey, who was sitting to my right. Next, we placed corn, grapes, pineapple, and chicken behind the chair of Lisa. In short order, we ran through the list and placed images behind the chairs of each of the people sitting at the conference table. It only took a few repetitions before my group of memorizers had it down.

Then it was showtime. Dr. Oz bounded onto the stage and we launched into a lively discussion of brain health, including the benefits of “working out” your memory skills. I declared that memorizing long lists of random items isn’t actually all that hard. That anyone could do it. Of course, it was time to prove my point. Dr. Oz called Stacey onto the stage, and without missing a beat Stacey recited the twenty words in perfect order. Then she did it in reverse order.

Once you’ve learned a technique, memorization is easy. And, as you now know, the more you do it, the better you get. Practicing is so simple it’s almost child’s play. (In fact, I’ve taught my own children simple memory techniques and encourage them to practice.)

Give it a try. Make a list of twenty random items, chunk them in groups of four, create evocative images, create a story for each chunk, and away you go.

Practice reciting the stories until you’ve committed them to memory. (Hint: It shouldn’t take long!)

1. _______________

2. _______________

3. _______________

4. _______________

5. _______________

6. _______________

7. _______________

8. _______________

9. _______________

10. _______________

11. _______________

12. _______________

13. _______________

14. _______________

15. _______________

16. _______________

17. _______________

18. _______________

19. _______________

20. _______________

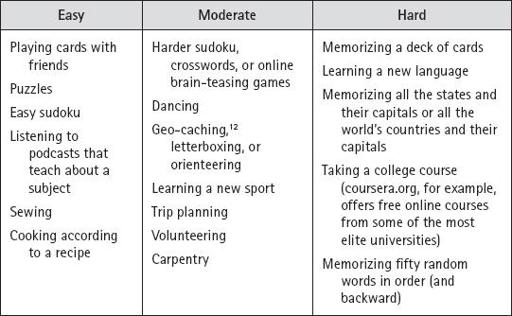

Brain-Building Activities

There are more brain-building activities than I could ever hope to list here. But I’ve included some examples of activities, grouped by level of difficulty. In general, the harder your brain works, the bigger the benefit, although keep in mind that even small efforts add up over time. I’d love to see you memorize a deck of cards, but if all you can manage for now is a puzzle, it’s far better than throwing in the towel and doing nothing.

Your Rx

Track 1

If you’re a cognitive couch potato—you do little to stimulate your brain, aren’t socially active, and rarely attempt to memorize facts or names—this track is for you.

Week One:

Practice memorizing a list of eight random words a day, three days a week, using my tips above. (Hint: Use a newspaper or magazine to help you pick random words for memorization.)

Week Two:

Practice remembering a list of twelve random words a day, three days a week.

Week Three:

Practice remembering twenty random words a day, three days a week. Try to incorporate cognitive stimulation into your daily life as well. Think of it as the equivalent of taking the stairs rather than the elevator: add numbers in your head, play around with your electronic gadgets to see what new functions you can perform with them, read the directions and figure out how things work!

Track 2

If your life is somewhat socially and cognitively stimulating but you rarely take on activities that stretch your “memory muscle,” this is your track.

Week One:

Practice memorizing a list of twenty random words a day, four days a week. Try to incorporate cognitive stimulation into your daily life as well. See my suggestions in Week Three, above.

Week Two:

Practice remembering four new names and faces a day, four days a week.

Week Three:

Practice remembering five new names and faces a day, five days a week.

Track 3

If you’re socially active, your life or work involves mental gymnastics, and you’re already good at remembering names, this is your track. Your goal is to flex your “memory muscle” in new and challenging ways in order to enhance your cognitive flexibility.

Week One:

You’re already good at this, so practice remembering thirty-six items three days a week, and ten names two days a week.

Week Two:

Pick a new hobby or take a new class. Spend one hour this week learning a new skill: maybe a new language, wine tasting, bird watching, photography, dancing—whatever you like. Remember, the best options are those that cross-train both your body and brain.

Week Three:

Learn to memorize a deck of cards. Nelson Dellis explains his method online: http://climbformemory.com/2010/06/08/how-to-memorize-a-deck-of-cards, but other mnemonists describe different techniques online and in books. Pick one and start practicing!

N

OW THAT YOU

know the science behind a bigger brain, you’re ready to start building that eight-cylinder engine beneath your skull. Over the next twelve weeks, you’ll implement a custom-crafted plan aimed at boosting BDNF, increasing oxygen flow, and training your brain to work within the ideal alpha zone.

You already got a glimpse of the plan, the track system that I previewed at the end of each chapter. Now you’ll fully implement your own plan, following your selected track for each brain-boosting area each week and rating yourself on your effort. I recommend that each Sunday evening you rate yourself on the week before and plan your brain-building efforts for the week ahead.