BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (29 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

“Only be careful, Mr. Nast, that you do not first put yourself in a coffin.”

34

Almost lost in the cacophony were complaints from Catholics and Irish leaders over Nast’s constant ugly stereotyping of immigrants and the Church. The journal

Irish People

protested his putting a rum bottle in every Irishman’s pocket and

Catholic World

objected to his dressing Tammany figures as priests and bishops. When the

New-York Times

reprinted a

Harper’s Weekly

anti-Catholic column, an offended reader highlighted the bigotry of connecting Tammany corruption with religion: Tweed, Sweeny, and Connolly “as individuals [are] corrupt and criminal, … not as Democrats, even, much less as Roman Catholics, that they are on trial.”

36

But if any of these groups expected an apology, they were barking up the wrong tree.

Harper’s Weekly

instead blasted what it called the “astounding insolence” both of

Catholic World

and the Pope himself, citing a recent Vatican pronouncement that secular governments exercised rights “only by the permission of the superior authority, and that authority can only be expressed through the Church”—suggesting Church supremacy over law.

37

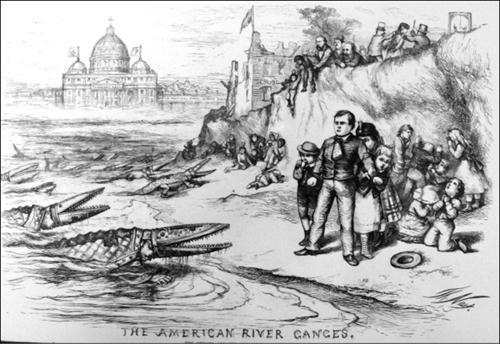

Harper’s Weekly, September 30, 1871.

Nast gave his own sharp response: a full-page illustration called “The American River Ganges” showing a group of young school-children huddled in fear on the banks of a river as dozens of crocodile-like creatures crawl from the water, mouths agape, teeth bared, ready to strike. But on closer look, the reptiles actually are Catholic priests and bishops, their hats and vestments transformed into scales and jaws. In the distance, Tammany Hall is seen as St. Peter’s Cathedral from the Vatican, a “political Roman Catholic School” at its side, a public school in ruins, and Tweed himself leaning over the riverbank smiling at the spectacle.

38

All the while, Nast’s anti-Tweed cartoons were making Fletcher Harper and his septuagenarian brothers a bundle of money:

Harper’s Weekly

circulation had tripled by August 1871 to 300,000; every newsstand window drew crowds of giggling readers when the new weeks’ issue arrived for sale.

-------------------------

Where was Tweed all this time as crisis after crisis gripped his city—the Orange riot, the

Times

Secret Accounts, the freeze in city credit, the citizen denunciations, the Nast cartoons? When in town, he avoided reporters and public meetings. Mostly, he enjoyed the summer social season in Greenwich. If he cringed at the attacks privately, he didn’t show it publicly. By every outward appearance, he seemed unattached, unconcerned, and unembarrassed.

Harper’s Weekly

boasted that summer that Tweed had snapped at seeing some of the Nast cartoons, saying he “doesn’t care a straw for what is written about him, the great majority of his constituency being unable to read, [but] these [Nast] illustrations, the meaning of which everyone can take in at a glance, play mischief with his feelings.”

F

OOTNOTE

39

Tweed was also quoted as telling a friend “if the people got used to seeing [me] in [prison] stripes, they would soon put [me] in them.”

40

But he kept any such reaction well hidden. His public silence infuriated many; diarist George Templeton Strong took it as an admission of guilt “

pro confesso

.”

41

Asked in mid-August whether he’d stolen money from the city, Tweed answered “This is not a question one gentleman ought to put to another.”

43

Instead, as OakeyHall wrestled with the crisis back home, Tweed led the festivities for the July gala christening of the new Americus Club lodge house on Greenwich’s Indian Harbor—a festival of back-slapping, cigars, and fancy nautical costumes. Tweed had sunk more than $118,000 of his own personal money into the club between June 1870 and July 1871 to help finance its new building—its 225 cuspidors, barber chair, upholstered tapestries and divans, smoking rooms, dining halls, and moorings for yachts and sailing sloops.

44

As club president, he’d arranged for it to rent the small island he owned nearby in Long Island Sound called Tweed Island, accessible from the lodge by a naphtha-powered launch. He brought Tammany political friends out for weekends to enjoy sailing, sipping champagne, and slurping oysters on cool summer nights.

Back in New York, his name appeared publicly only in connection with his latest business deals. In addition to the new Viaduct Railroad, newspapers carried accounts of Tweed’s joining a well-heeled group of humanitarians putting up $35 million to rescue thousands of Paris Commune prisoners still being held for deportation by the French government. His new Lower California Company, whose directors included national figures like Illinois U.S. Senator John Logan and local celebrities like August Belmont and former New York governor John Griswold, offered to colonize the French prisoners on the American west coast, giving each man fifty acres if France paid for food and transport.

45

Late in August, New York society flocked to join Tweed’s two oldest sons Richard and William Jr. for the gala opening of the Metropolitan Hotel, which Tweed had spent over $450,000 on renovating that summer, in addition to the $90,000 he paid in annual rent for the building.

46

Over a thousand invited guests came to gawk at the hotel’s elegant improvements: its 400 rooms each held new gold and walnut furniture, Turkish-styled walnut bedsteads, Royal Wilton and Axminster carpets covering buffed hardwood floors in the bridal suite, ballrooms, and corner suites, walls covered with blue and satin lace curtains. Afterward, the two brothers stood side-by-side, both in dark suits and diamond pins, as the hotel opened its grand ballroom for a luscious feast from the kitchen of

chef de cuisine

M. Ludin:

saumon froid a la ravigote, pate froid de Gibier aux truffes, petits poulet rogis, jambon de Virginie

, capped by Irish harp, champagne, ice cream

napolitaine

, and coffee

a la Francaise

.

But as Tweed and his sons enjoyed their high-profile parties, Oakey Hall and Richard Connolly, their honors the mayor and comptroller, grappled with the unfolding disaster: When the mayor appealed to New York’s business leaders early in August for help in addressing the credit crisis sparked by the

Times

’ exposes—asking that a “large and influential committee of well-known and upright citizens” be chosen to take a neutral look at the city books

47

—Wall Street abruptly slapped him down. Its top citizens wanted no part of it, having seen their friends John Jacob Astor, Moses Taylor, and Marshall O. Roberts played as dupes, vilified by the

New-York Times

and ridiculed by Thomas Nast. Instead, they demanded the city make a full, clear statement of its finances before they’d lift a finger.

48

When Hall and Connolly did finally produce their financial report on August 23, it started only more squabbling. Again, the mayor asked business leaders to join him in reviewing the numbers

and, this time, they agreed, but demanded a larger role and named eight leading financiers to join the project who insisted on getting a full chance to study the details.

49

Meanwhile, Oakey Hall kept irritating the wound with his constant nibbling attacks at his accusers. He still couldn’t get George Jones’ personal affront off his mind. “The gross attacks of a partisan journal upon the credit of the city should be answered,” he wrote in a circular for the City Council.

50

He asked city employees not to eat their lunches at the popular cafeteria in the basement of the

New-York Times

building on Park Row, just across the street from City Hall. At the same time, he pressured conductors on city trains to prevent sales of the

Times

on local newsstands, forcing George Jones to appeal directly to New York Central Railroad owner William H. Vanderbilt who pressured to prevent any “discrimination against any respectable journal on our trains.”

51

Hall raised the biggest stink of all by announcing plans to evict the

Times

from its own office building. The Old Brick Church property—the lot on Park Row that the

Times

had purchased back in 1857 for erecting its current structure—actually had once belonged to the city, the mayor argued, and its sale to the newspaper had been illegal. Speaking through the

Sunday Mercury

, he announced plans to ask the state Supreme Court to seize the newspaper, put it under control of a receiver, eject it from the building, and demand it pay six years’ back rent. “The litigation promises to cover a very long period, and a number of Republicans have volunteered to raise a fund to aid the owners of the

Times

,” the

Sunday Mercury

reported.”

52

A few days later, city aldermen met and voted to initiate formal proceedings to recover the property.

All this agitation by the mayor brought the expected result: Louis Jennings at the

Times

launched his own wave of new late-August attacks. Using the same front-page banner format of the original Secret Accounts, he presented a list of eye-catching items from Oakey Hall’s own latest financial report: more money for vacant armories, $27,200 for safes at the new Courthouse, $82,184 in advertising payments to twenty-three newspapers, and the more serious ticking time bomb: $3.3 million in interest paid on the city’s growing pile of bonds. A separate column pin-pointed cost overruns on the new County Courthouse: budgets of $6.4 million between 1852 through 1871 for the building had been dwarfed by actual payouts in 1869 and 1870 of $6.9 million, plus line items of $7,500 for thermometers and $175,000 for carpets. “Property owners may well be alarmed at the new exhibit we now place before them,” he charged.

53

On August 21, Oakey Hall sued the paper for libel.

All through August, Hall and Connolly appealed to Tweed and Sweeny to please come home and help put out the fire, but weeks went by without the four getting together. Sweeny, from his summer house upstate, made a special point to stay away, prompting whispers of a falling-out within the Ring.

Sweeny returned to New York City for one weekend that summer and used the chance secretly to begin digging graves for his friends, quietly contacting allies to deny any connection with the frauds, blame Connolly and Tweed for the debacle, and even going so far as to plant stories in friendly newspapers that Connolly should resign so he, Sweeny, the post-scandal survivor, could take his place.

F

OOTNOTE

54

Why didn’t Tweed speak up or take control? Was he too busy relaxing to appreciate the danger? Or had he grown so accustomed to power that he considered himself untouchable? Did he see this as just another political attack that inevitably would do just as Jennings and Nast said: blow over?

Legally, Tweed had little reason to panic: So far, the

Times

had failed to make a case against him. Its Secret Account stories had shown the city’s being gouged by inflated bills and himself, the mayor, and Connolly being perhaps negligent or sloppy in approving them, but no evidence to date actually connected any of the misspent money to Tweed personally. Where did it go, they asked? Without a clear answer, reformers or prosecutors couldn’t lay a finger on any of them.

Nast himself laid out the legal ambiguity in perhaps his most famous

Harper’s Weekly

cartoons from that summer. “Two Great Questions,” he’d titled it. First: “Who is Ingersoll’s Co?” In answer, it showed a giant Tweed (with giant diamond) and all his Tammany hangers-on crouched hiding behind him like pygmies. Second: “Who stole the people’s money?” For this, Nast drew all the members of the Ring—Tweed, Sweeny, Connolly, Hall, the contractors and the Irishmen—all standing in a circle, each pointing to the person on his right, saying “Twas him.”

55