BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (6 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

At the time, the change was dramatic. Up through the 1850s, very few Americans ever saw likenesses or photographs of popular leaders, places, or events. Most who voted for Jefferson or Jackson, for instance, had little idea what these people looked like. Rural farmers often had never seen cities like New York or Chicago, let alone ocean-going ships or European capitals. Most city dwellers could barely envision prairies, mountains, or small towns. Other than rare, expensive paintings, broadside posters during political campaigns, book illustrations, or engravings from printers like Currier and Ives, Americans had to rely on words to picture people and places beyond the immediate horizons of their lives.

By the late 1850s, New York alone had spawned almost a dozen new illustrated journals and readers began snapping them up; with the onset of Civil War, this demand exploded.

Leslie’ Illustrated

was a sixteen-page weekly costing ten cents when Nast started working there at a salary of $4 per week. Thrown into the fray, he quickly learned the symbolic language of image, caricature, and satire, using symbols like the British lion or Uncle Sam. By 1860, he’d moved his pen to another weekly, the

New York Illustrated News

, which gave him a chance to see the world. They sent Nast to England to cover the championship prizefight between American John Heenan and British champion Thomas Sayers—a great sporting event of its day.

47

Nast then traveled south to Italy to join patriot Giuseppi Garibaldi on his march of conquest from Genoa to Naples. For four months, Nast’s drawings of the fighting in Italy appeared in New York weeklies; his exposure to the violence, courage, and devastation would later inspire his images on America’s own Civil War. Returning home to New York City, he married his long-time friend Sarah Edwards, re-joined

Leslie’s Illustrated

now at $50 per week, and followed newly-elected Abraham Lincoln to Washington, D.C. to draw pictures of Lincoln’s inauguration. He became an unabashed admirer of the new president of the United States.

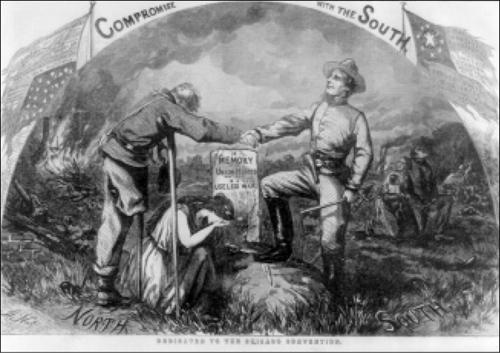

“Compromise with the South,”

Harper’s Weekly, September 3, 1864.

By then, his craft had matured. “It is full of life and character,” one fellow artist said on seeing an early drawing, “as everything is which comes from Mr. Nast’s pencil.”

48

Abraham Lincoln faced a difficult wartime reelection campaign in 1864 and Nast threw himself eagerly into the fray. Nast saw politics as a natural extension of the war. Democrats in 1864 had nominated former Union General George B. McClellan on a peace platform promising a negotiated end to fighting—what Nast, a Lincoln backer, saw as shameful surrender. New York Democrats had once again nominated for governor Horatio Seymour, the Copperhead who’d notoriously called draft rioters “My Friends.”

Nast had seen the July 1863 riots firsthand; he’d just returned from the Virginia battlefront when they’d begun. At their height, an Irish mob had surrounded the Harper building on Franklin Square and forced it to close; employees—probably Nast among them—had barricaded the doors and taken up rifles against threatened attacks. Nast had ventured out onto the streets with pad and pencil at one point to sketch scenes of the mayhem, including one scene of children dancing around the body of a murdered soldier.

Nast saw the 1864 political campaign as a chance to get even with Copperhead politicians who’d allowed these outrages. Already, he’d produced one drawing that caused a national uproar. Titled “Compromise with the South,” it showed an arrogant Confederate officer stepping with his boot on the grave of a dead Union soldier as a crippled Union veteran turns in shame and Columbia as a woman kneels in tears.

49

“Dedicated to the Chicago [Democratic] Convention,” read the caption—directly fingering candidate McClellan. Lincoln’s campaign printed an estimated million copies of Nast’s cartoon and distributed them before Election Day.

Now, just days before the November voting, he’d produced another. A new scandal had erupted. The State of New York licensed agents to collect votes from tens of thousands of soldiers at the front line. These agents had been caught red-handed in a variety of frauds: tricking soldiers into signing blank ballots, forging signatures, filling in names of wounded, dead, or even non-existent men on Democratic papers—steps all designed to turn votes for Lincoln into votes for McClellan.

F

OOTNOTE

Nast pounced on this fraud for his new cartoon, barely a week before Election Day.

The charges had created a sensation. Many of the cheated soldiers were veterans of that summer’s Wilderness campaign, a string of carnages across Virginia from Spotsylvania to Cold Harbor, whose units still faced Robert E. Lee’s entrenched forces at Petersburg.

50

Hundreds lay crippled or dying in field hospitals. Thomas Nast’s talent lay in his ability to translate such a complex scandal into a simple compelling image that even a child could understand.

Nast preferred to work from his home, a small house on West 44th Street, the city’s upper fringe, on his drawings for

Harper’s Weekly

.

51

His wife Sarah had recently given birth to their first child, a baby daughter. Sarah often read to him aloud from newspapers or books as he worked; novels by Thackeray became special favorites for them. Nast used Sarah as his model for Lady Columbia in several cartoons. “I think you are a lucky fellow to have so good a wife, and she’s a lucky wife to have so good a husband,” wrote his friend James Parton.

52

Nast sometimes drew so intensely that his hand would freeze in painful cramps.

Thomas Nast as a young prodigy.

Now he had produced an evocative new drawing based on the scandal. Reaching the top floor of the Franklin Square building, he quickly found the office of his publisher and stepped inside. Fletcher Harper liked what he saw. His broad face, deep eyes and wide whiskers, may have broken into a smirk at Nast’s latest production; maybe he laughed out loud after laying it across his desk.

Harper, 57 years old, was the youngest of the four Harper brothers who’d started the publishing business decades earlier. A devout Methodist who wore black frock coats, he had an “earnest and definite way of expressing himself which was clear and impressive,” his grandson John Harper wrote.

53

Within the company, he took responsibility for the two Harper journals,

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

launched in 1850 and now the political

Weekly

begun in 1857. He’d taken a quick liking to his magazine’s young prodigy—he called him Tommy and used his work as an example for other staff artists. Beyond personal warmth, Harper appreciated that Nast made money for him and his brothers; a good Nast cartoon could boost wartime sales of

Harper’s Weekly

by tens of thousands at ten cents apiece.

Harper studied Nast’s newest drawing and saw it fitting nicely into his own political agenda: reelecting Abraham Lincoln. Its caption read simply: “How Copperheads Obtain their Votes.” In it, Nast had focused on the scandal’s most grisly detail—stealing the votes of dead soldiers. It showed two men dressed like grave robbers in a deserted cemetery at night, huddled in shadow around a fresh grave marked “Killed in the War of the Union.” One man scribbles the name from the stone on a small paper as the other watches for intruders. But rising above them from the grave, visible only to the reader, is the ghost of the fallen soldier. He stands tall and glares down at his tormentors, his face torn by shock and anger. “Curse upon you,” the ghost pronounces. “Curse upon you for making me appear disloyal to my country for which I have fought and died.”

54

In a few pencil strokes, Nast had created a deadly political weapon, evoking anger at the defilers, pride in the fallen soldier, and defiance at corruption! Harper approved it quickly and sent it to the engravers.

Harper’s Weekly

would feature it in its November 12 edition hitting newsstands on the Saturday before Election Day, an edition devoted almost entirely to urging voters to cast the Lincoln ballot.

The strategy worked. Lincoln would carry New York State in 1864, but only by a whisker—50.5 percent for him versus 49.5 percent for McClellan. Separately, Horatio Seymour would be defeated as governor.

55

Afterward, Lincoln would praise the young artist who helped tilt the balance his way: “Thomas Nast has been our best recruiting sergeant,” he’d write. “His emblematic cartoons have never failed to arouse enthusiasm and patriotism, and have always seemed to come just when these articles were getting scarce.”

56

By the end of the Civil War, young Tommy Nast had emerged not just as a cartoonist and war illustrator but as a force in American politics. Through his pencil, he’d proven he could sway a national election and savage enemies from a national platform with a riveting new technology, the power of printed pictures.

In all his attacks against Democrats during the war, though, Nast in his cartoons never mentioned Tammany Hall itself, chronically the center of local corruption. Nast would have respected Tammany’s pro-war stance and no evidence ever connected Tammany specifically with the 1864 soldier vote frauds. But perhaps there was something more: Tom Nast still held fondly to a memory from childhood. As a young boy in Manhattan in the late 1840s, he’d enjoyed running about in his knickers through city streets with friends and a favorite pastime had been to follow the showy firemen’s companies and their loud, bell-ringing pump-engines racing to the scenes of giant fires, spectacles that terrified and fascinated him. Nast as a boy loved the excitement, the competition between rival fire teams, and clearly remembered his favorite, the “Big Six” volunteers. He’d particularly liked their emblem: the tiger painted in bright colors on the side of their shiny silver engine. He’d even made a point to study the original drawing of the tiger, a reproduction from a French lithograph hanging in a store on James and Madison Streets.

At the time, Nast didn’t know the big strapping fellow in the red shirt, the chief of the fire company he so admired. But, years later, his drawings of corrupt politicians cheating voters like those frontline Civil War soldiers would lead to his downfall. By then, everyone would know the big man’s name—Bill Tweed.

CHAPTER 3

BALLOTS

“ The fact is New York politics were always dishonest—long before my time. There never was a time you couldn’t buy the Board of Aldermen…. A politician coming forward takes things as they are. The population is too hopelessly split up into races and factions to govern it under universal suffrage, except by the bribery of patronage or purchase.”

—

TWEED

, in an interview from jail, October 25, 1877, about six months before his death.

1

In the election of 1868, voting fraud reigned at the polls in New York City. Civil War hero General Ulysses Grant won the White House, defeating Democrat Horatio Seymour, the former New York governor, Civil War Copperhead and sympathizer with draft rioters. But Tammany Hall took all the important city and state prizes.

On Election Day, marshals arrested dozens of rabble-rousers after rival police forces threatened riots at the polls. Final vote counts clashed wildly with local registration lists and newspapers exploded with charges and countercharges. Republicans claimed at least ten thousand fake or illegal ballots had been cast; led by Tribune editor Horace Greeley and the Union League Club, they demanded a thorough probe.

The voting irregularities were so blatant that the United States Congress in Washington, D.C. assigned a special Select Committee to investigate.

-------------------------

S

AMUEL Jones Tilden kept his distance from Bill Tweed. They might be two top leaders in the New York Democratic Party, but they traveled in different circles. Tilden, nine years older, headed the state committee; he socialized with Swallowtails—wealthy Democrats named for the formal dinner jackets they wore at the posh Manhattan Club—and had amassed a fortune as a railroad lawyer. Tweed, by contrast, he considered merely a local chief and a post-war “shabby rich.” Tilden’s Manhattan Club would not offer Tweed a membership for years.

2

Today, Tilden arrived at the snow-crusted sidewalk in front of the United States courthouse at 41 Chambers Street near City Hall just minutes before Tweed. He came in a separate horse-drawn carriage. The U.S. Congress’ recently appointed Select Committee on Alleged Election Frauds had called him and Tweed both to testify on that same morning, December 30, 1868, one after the other.