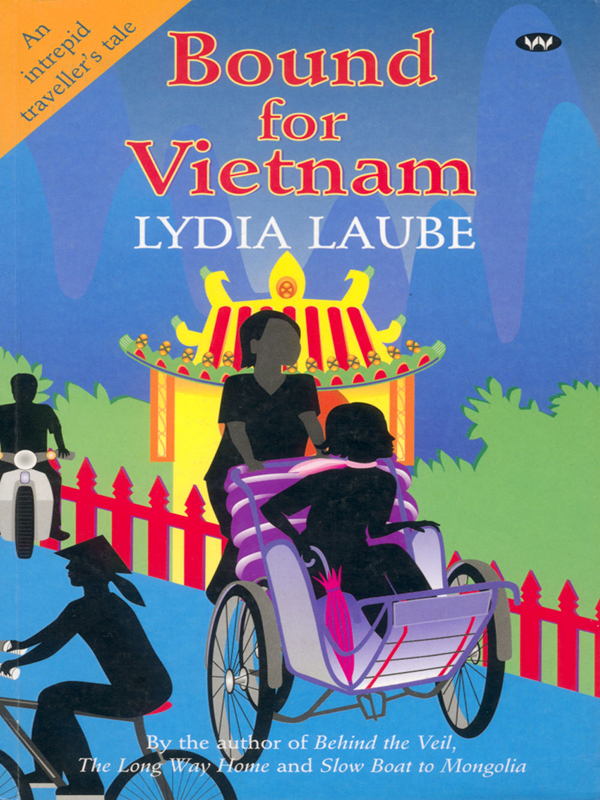

Bound for Vietnam

Wakefield Press

Bound for Vietnam

Believing that to travel hopefully is better than to arrive – and she sometimes almost doesn’t – Lydia Laube is one of Australia’s favourite travel writers. Lydia can never resist a challenge, and her books,

Behind the Veil: An Australian Nurse in Saudi Arabia

,

The Long Way Home

,

Slow Boat to Mongolia

,

Llama for Lunch

,

Temples and Tuk Tuks

, and

Is This the Way to Madagascar?

, tell of her alarming adventures in far-flung places of the globe.

When she is not travelling, Lydia Laube chases the sun between Adelaide and Darwin.

Bound for Vietnam

Bound for Vietnam

LYDIA LAUBE

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

Australia

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 1999

Reprinted 2007

This edition published 2010

Copyright © Lydia Laube, 1999

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Edited by Jane Arms

Cover designed by Nick Stewart, design BITE, Adelaide

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-publication entry

Laube, Lydia, 1948– .

Bound for Vietnam.

ISBN 9781862549012

1. Laube, Lydia, 1948– – Journeys. 2. Vietnam – Description and travel. 3. China – Description and travel. I. Title.

915.9704

Contents

13 Snake Livers and Jungle Juice

By the same author

Behind the Veil

Is This the Way to Madagascar?

Llama for Lunch

Slow Boat to Mongolia

Temples and Tuk Tuks

The Long Way Home

It’s funny how life turns out when you are travelling. I had set off from Timor planning to reach China by sea, cross that country by train to Mongolia and then come home. But a chance encounter with a Welshman on the Trans-Siberian Express en route to Ulaan Bator had made me decide once again to take the long way home. I had ended up in Tianjin, a great port washed by the Bohai Sea on China’s north-east coast. It sits on the banks of the Hai River, 120 kilometres from Beijing. I now planned to sail down the coast of China to Shanghai, ride riverboats as far south as I could on the Yangtze, go to Guangzhou where I had heard it was possible to get a visa for an overland crossing into Vietnam, make my way over the mountains to the border and, with luck, be allowed to enter Vietnam’s far north.

The train journey from Beijing had taken me only two hours. I got off at the station with a minimum of fuss and a fellow-traveller, a Chinese man, helped me with my bags.

My guide book labelled Tianjin ‘the most expensive town in China’. It was said to be a hopeless place to find a reasonably priced hotel room that was not off-limits to foreigners. Near the railway station exit I came across a table run by an official-looking woman whom I deduced, from the pictures she displayed, was selling hotel rooms. I reckoned that in these circumstances some bargaining might be in order. I asked how much. The woman wrote a figure on a piece of paper. I said, ‘Too much. I only want a single room.’ I wrote 200. She used a nearby public phone – there was no office, only the table – and returning said, ‘Okay,’ and indicated that I should go with a man she now had in tow. He turned out to be the driver of one of the little yellow vans that served as taxis. By now it was ten o’clock at night and I went willingly.

He took me to a smart hotel, where three giggling girls presided over the reception desk. They intimated that I could have a room and wrote a price: 488 yuan. I recoiled in mock horror. ‘No, no,’ I said, ‘I can’t afford that,’ and began to bargain with them. We finally settled on 188 yuan.

That accomplished, it seemed to take all three young ladies forever to fill out the myriad forms that were necessary to get me admitted. And then they could not scrape up enough money to give me twelve yuan change. ‘Come back tomorrow’, was all they said. It’s no good travelling in China without cash. You need lots of the gorgeous stuff – no one will trust you inside their establishment unless you pay up front, preferably in small denominations.

The accommodation I was finally let loose in was far above the standard to which I had become accustomed in China. And everything worked – airconditioner, lights, hot water! The toilet flushed. But there were the usual faults. The hand-basin was loose, and the shower was impossible to use; the water wouldn’t mix and was either burning hot or stone cold. The young female room attendant showed me how to work everything in my room and a bell boy, the first I’d encountered on my travels, delivered and stowed my bags.

The hotel dining-room was crowded at breakfast, perhaps because the meal was included in the price of the room. The food was not riveting, but I had got up at the crack of dawn to indulge in it, so I was determined to persevere. Rice and pea gruel, which tasted like warm water that had had rice washed in it, was followed by a cold hard-boiled egg, some of the pickled cabbage I had come to like, and dumplings. Tianjin is famous for its steamed dumplings – they are even exported to Japan – and these were delicious. There were also some strange-looking fried patties that were definitely an acquired taste –meat spread with peanut butter, sprinkled with sesame seeds and dipped in batter.

Outside the hotel, the bell boy, who was most concerned about where and how I was going, helped me get a taxi to CITS, supposedly the place to go if you need to buy tickets, or get help with your travel arrangements. CITS was located in a marvellous great building with China International Travel Service blazoned across its front. The foyer of the building was desolate except for the usual guard who sat behind a glass screen like a museum exhibit. In China I found that everyone who was exposed to the public was, wherever possible, behind barricades. Through the peephole in his glass case the guard indicated that I should state my business.