Brain Over Binge (12 page)

Authors: Kathryn Hansen

This is a question I had to grapple with after my recovery, because if I'm questioning everything I learned in therapy, I should also question diagnostic criteria for eating disorders. It is true that bulimia and BED cannot exist without binge eating, but should binge eating be the defining characteristic of these disorders? Traditional therapy teaches that bulimia and BED are not truly about food and weight, but one look at the

DSM

criteria for diagnosis tells a different story. My therapists seemed to treat me as if the

DSM

was wrong, or at least vastly insufficient.

If eating disorders are really not about food and weight, then we shouldn't define them as such and we should redefine them based on whatever therapists think they are really about—possibly an inability to deal with negative feelings, a lack of happiness, low self-worth, an abundance of family conflicts, or a flawed personality. From a more scientific perspective, eating disorders could possibly be defined on the basis of biological or genetic risk factors, or the neurochemical processes involved in conditions that can occur alongside bulimia, such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

39

In other words, if the experts are going to treat eating disorders as if eating is not the problem, then they should also define eating disorders as if eating is not the problem.

Personally, I believe the disorders are defined correctly. If treating all of the supposed underlying psychological causes and risk factors cured everyone, then maybe I would change my mind; but until definite proof comes out that eating disorders really have nothing to do with eating, I will continue to believe they have everything to do with eating. I will continue to believe that if I don't binge, I am not bulimic.

16

: Why Did I Binge?

A

s soon as I stopped binge eating, it became clear to me why I had binged for so many years—and the answer was a far cry from what I learned in therapy. I didn't binge to satisfy deep inner emotional needs. I didn't binge because I had a disease that I was powerless against. I discarded the hypothetical and convoluted reasons why I binged, and I realized that there was only one concrete and clearly identifiable reason:

I binged because I had urges to binge.

Although this reason seems obvious and overly simplistic, it explained every binge from the time I ate eight bowls of cereal that March morning in high school, to the times when I drove to countless fast-food restaurants and gas stations in college, to my final true binge shortly after reading

Rational Recovery.

My urges to binge eat were not

symptoms

of anything—they

were

the problem. There was nothing about my poor body image, low self-esteem, high anxiety, depressive tendencies, family stressors, or any other problem for that matter that made me binge eat. The urge to binge was the only direct cause of every single binge—regardless of when, where, how, or why the urge surfaced.

Once I stopped acting on my urges to binge, I saw clearly that the real problem wasn't my life, personality, or family history. The problem was that I had strong urges to binge eat, at many different times and in many different places; and I gave in to those urges again and again. If, at any point during my bulimia, I would have been able to take away the urges to binge, I would have taken away my bulimia. I first learned this lesson while on Topamax.

If I hadn't had a desire to binge, I wouldn't have binged for all those years—it was that simple. At times during my bulimia, I did not have high anxiety, but I still binged. At times during my bulimia, I wasn't depressed, but I still binged. At times, I felt OK with my body and myself, but I still binged. Working on my other problems in order to stop binge eating was a waste of time, because it wasn't addressing the real cause of binge eating: the urges to binge.

I learned in therapy that the causes of binge eating were the thoughts, emotions, interactions, moods, or life events that supposedly triggered the binges. Once I stopped binge eating for good, I realized this was glaringly untrue. Triggers were—at best—an indirect link to my binge eating, not the cause. I'll discuss triggers in detail in Chapter 35; but for the time being, I'll just say that it was possible for certain thoughts, feelings, interactions, moods, or life events to give rise to my urges. However, once the urge surfaced, it was the urge that was the real problem. It was the urge—and all the thoughts, feelings, sensations, and cravings that came along with it—that caused me to binge; and whatever may have theoretically caused the urge to surface was no longer relevant.

Of course, all of my thoughts, emotions, interactions, moods, and the events I faced mattered significantly to my

life;

but they did not matter to my recovery from bulimia. What I learned to do with the thinking skills from

RR

was to target the real problem—the urges to binge. Since an urge to binge always appeared before a binge, it only made sense for me to learn how to manage those urges and eliminate them, which I was able to do rather easily.

Through the years of my binge eating, sometimes my urges were predictable—such as when I came home from school or work to an empty house, while trying to go to sleep at night, when I woke up in the middle of the night, during meals that contained fattening or sugary foods, after drinking alcohol—and sometimes my urges to binge were more erratic, surfacing when I least expected them.

My urges to binge were not simply needs to indulge in a little extra cheesecake, another piece of chocolate, or some more potato chips with lunch—the mind-set was different, much more fierce, animalistic, focused, and seemingly uncontrollable. These urges were much more powerful, much more consuming, and much more relentless. They were nonsensical desires to stuff myself, to eat all I could as fast as I could, to swallow very large amounts of food until I was well past the feeling of fullness.

Although my urges to binge were very different than the wish to indulge in a little treat, they were often preceded by a rather innocent craving for a small indulgence. But, often, as soon as I gave in to the craving for the small indulgence, the all-powerful urge to binge appeared. It was as if the small indulgence kindled the urge, setting me aflame with desire for more; and more often than not, I quickly found myself eating much more than I had planned and spiraling into a binge. Sometimes I knew beforehand that a small indulgence would inevitably lead to an urge to binge, and sometimes I was honestly caught off guard. The problem wasn't the small indulgence; the problem was the urge to binge that occurred as I gave in to innocent cravings.

On the other hand, my urges to binge often occurred in situations where there was seemingly no good reason for me to be thinking about food—times when there was no food around me, such as in the middle of class or the middle of the night. Sometimes ideas about food simply popped into my head, and one thought led to another until I was experiencing a strong urge to binge. The little ripple of thoughts about food led to a wave that often swelled to its full height in an instant; but other times it grew over several minutes, hours, or even days—so that my urges to binge sometimes began a long time before the actual binge.

The urges to binge didn't always have to be strong to convince me to indulge. Sometimes I began binge eating at the first hint of a craving, and in those instances, the urges were barely perceptible. At other times, it seemed like I simply found myself in front of the refrigerator without consciously wanting to be there. However, no matter how mindless my binge eating felt sometimes, there was always some inkling of desire, some tempting thought that preceded each and every binge.

So when I speak of an "urge" to binge, I'm not always talking about an all-consuming craving; because sometimes, I'd simply think,

I'm going to buy some food and binge tonight, it's no big deal,

and I did. There were many weeks during the course of my bulimia when I resigned myself to my problem, didn't bother fighting my desire to binge, and even planned binges at predictable times. Allowing scheduled binges kept my more powerful cravings in check, but even a plan to binge was a form of an urge. Urges ranged from a simple thought to desperation—and everything in between.

Regardless of the specifics, the bottom line holds: no binge ever occurred that was not preceded by an urge to binge. No matter how much time passed between my urge to take that first bite and when I actually took it, the urge was the only cause of each and every one of my binges. As much as a binge felt like an out-of-body experience, it was not. My binges did not result from some mysterious force that took over my body. Prior to each binge, I chose—whether it was over several hours or in an instant—to follow my urge.

Bulimics and all binge eaters are worthy people who simply become temporarily engulfed by urges to binge. Anyone in a bulimic's situation would probably do the same thing, because the drive to binge can be so incredibly compelling. It made me forget about all of my commitments, all the reasons I wanted to quit, all the shame and guilt I would experience after the binge, and all the people I would let down by binge eating. The urge to binge seemed to transform me into something that I was not: a ravenous, greedy, gluttonous, disgusting individual who cared more about getting large amounts of food than my family, my career, my health, or my life. I knew I was not that; and I know that no bulimic is that.

Sure, urges to binge caused my binge eating; but it certainly wasn't normal for me to have urges to binge. Before I explain how my recovery was possible, I need to explain why I had those urges in the first place. In the next five chapters, I'll talk about the reasons why I developed and continued having urges to binge, and why I kept following them.

17

: What Caused My First Urges to Binge?

S

ince urges to binge were the only one true cause of each and every binge, there was only one true cause of my first binge: urges to binge. But why did I develop those urges in the first place? Why did I have such strong cravings for food? Why did I feel compelled to eat eight bowls of cereal on that March morning of my senior year of high school?

Was I trying to stuff down emotions? Was I trying to comfort myself during a stressful time? Was it because of depression? Anxiety? Did I have a disease revealing itself through my urges to binge?

The answer was none of these.

My urges were not symbolic of unmet emotional needs, underlying psychological issues, character flaws. Yes, I had some problems and emotional stressors in my life at the time my first urges to binge appeared, but that alone did not give rise to those urges. There was only one true cause of my first urges to binge, and that cause was dieting. My restrictive eating habits, which I maintained for over a year and a half before my first binge, were the reason I felt compelled to eat so much sweet cereal that spring morning.

Dieting precedes nearly every case of a bulimia,

40

as it did mine. Not every teen who diets develops an eating disorder, so there are other factors involved; but even though there are some genetic risk factors,

41

biological factors, societal influences, personality features, and family characteristics

42

that put certain girls and women at higher risk of developing bulimia, bulimia rarely develops without a history of dieting. (Binge eating disorder, on the other hand, develops more commonly without an initial diet, a fact discussed extensively in Chapter 20.)

There indeed may have been factors that made

my

dieting in particular such a problem, which I will discuss in the next chapter; but without dieting, I would not have developed urges to binge, and I would not have developed bulimia. For the purposes of this chapter, it doesn't matter why I began dieting in the first place. All that matters is that I began restricting my food intake, limiting my calories, and this caused a problem in my brain.

Even though dieting and weight loss made me feel good about myself, something in my brain told me I was doing something terribly wrong. I started to obsess about food and think about it constantly, when prior to dieting, food simply hadn't been an issue in my life. I felt intense hunger and cravings for the types of foods I tried to limit, and I began having cravings to eat abnormally large amounts of food.

I'd chosen to diet at an age when my brain—more specifically, what I've been calling my "animal brain"—was sensitive to any form of food restriction; and in a strong survival reaction, my animal brain began sending out strong food cravings and urges to binge. My urges to binge were only my brain's normal and healthy reaction to dieting, and my binge eating was an "adaptive response"

43

to compensate for the food restriction.

Biologically driven binge eating is a phenomenon not exclusive to individuals with eating disorders. Prisoners of war, laboratory subjects, and other groups have shown similar excessive eating behavior after periods of chronic food restriction or starvation.

44

Furthermore, laboratory experiments with rats show that animals previously food-deprived but allowed to refeed to satiety and normal weight will binge eat if they are presented with highly palatable (tasty) food,

45

just as I did.

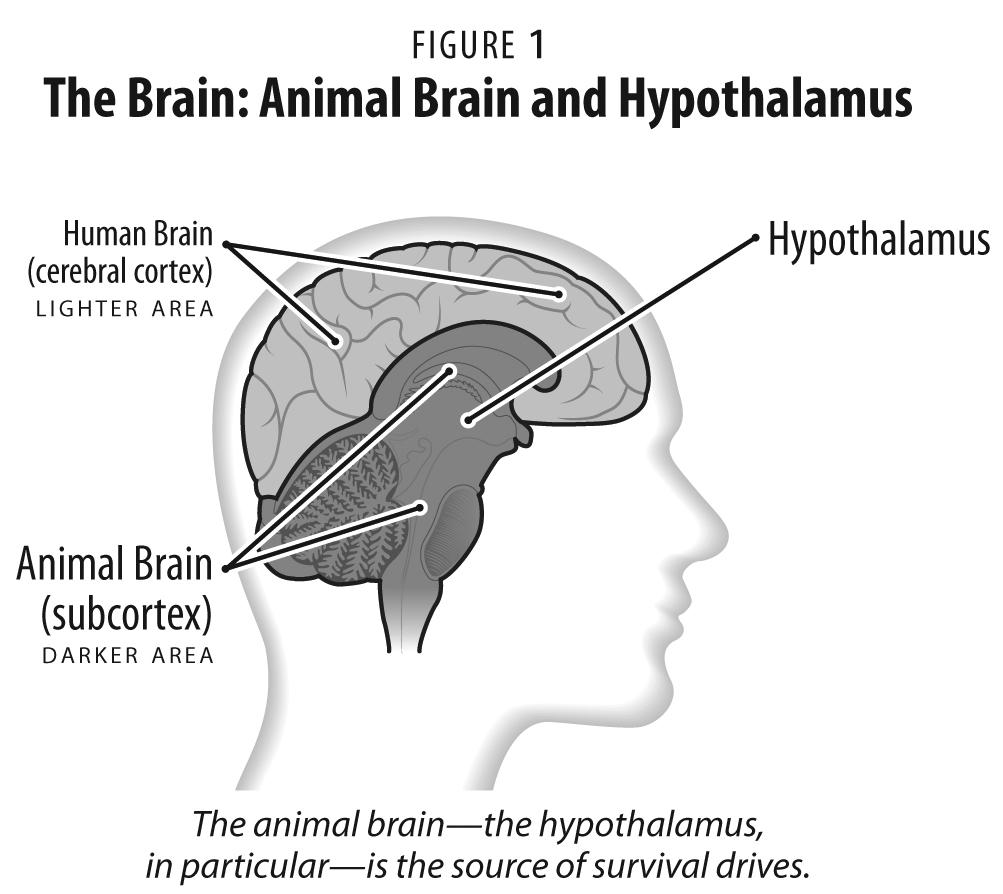

SURVIVAL INSTINCTS AND THE ANIMAL BRAIN

My first urges to binge were the result of my survival instincts. Survival instincts are our inherited tendencies to behave in ways that maximize our chances of survival. They are our automatic, primitive, and often powerful responses when one or more of our basic biological needs are not met. When the brain—specifically, the animal brain (see

Figure 1

)—senses a threat to survival, it automatically reacts, driving us to take action to protect ourselves. As I explained in Chapter 10, the animal brain is the automatic, unthinking, and irrational part of the brain that lies deep within, under the cerebral cortex, which is the higher-functioning, rational, human brain. True to its name, the animal brain directs the behaviors that are considered animalistic and instinctual. Its function and role in eating behavior and binge eating thus warrants a fuller analysis.

The animal brain interprets a diet as a threat to survival, and it naturally and forcefully attempts to protect the body from starvation. Even if the diet isn't severely restrictive and there is no danger of starvation, dieting is still against our nature, and our animal brain will put up a fight. Our body and brain switch into survival mode when food is deprived or limited. The body's metabolism slows down to get the most use out of every calorie, and other bodily processes change to conserve energy. The animal brain seems to focus on one supreme purpose: convincing us to eat.

The animal brain is a specific area of the brain, but its influence extends far beyond its boundaries. Probably the most dominant part of the animal brain is the hypothalamus, which has complex neural connections with other parts of the brain, giving it extensive influence and even a role in emotions and behavior.

46

The hypothalamus has been called the "chief subcortical center"

47

—the chief of the animal brain. The hypothalamus exerts its effects on the body through the autonomic nervous system, the somatic motor system, and the endocrine system.

48

The hypothalamus constantly monitors the body's internal and external environment, and coordinates appropriate behavioral and emotional responses that help ensure our survival. The hypothalamus is most certainly involved in eating behavior,

49

as well as in controlling other essential functions like body temperature regulation, control of blood pressure, and electrolyte composition.

50

Its job is to maintain a "relatively constant internal body environment"—what is called "homeostasis."

51

One way it maintains homeostasis is by regulating energy metabolism by controlling food intake, digestion, and metabolic rate.

52

Different parts of the hypothalamus have varying effects on the amount of food to be eaten.

53

The hypothalamic region involved in feeding has been called the "appestat," and within this appestat, there is a specific "hunger" center and a "satiety" center.

54

Stimulation of the hunger center in the hypothalamus increases an animal's urge to eat, but destroying this same hunger center produces an animal that refuses to eat. In contrast, destroying the satiety center produces an animal with ravenous appetite, and stimulating it inhibits the animal's desire to eat.

55

This shows what a large role the hypothalamus has in controlling the desire for food—and, quite likely, the urges to binge.

THE BRAIN IS NOT THAT SIMPLE

As appealing and helpful as it would be to point out one specific part of the brain and say,

That's where urges to binge arise,

it's not that simple. If the hypothalamus—or any other pinpoint part of the brain or specific neurochemical—was the only culprit in creating the strong urges to binge in a bulimic, the cure would be simple. We would only have to diminish the activity of that part of the brain or that neurochemical to cure bulimia (or, reversely, activate it to cure anorexia); but this is not the case.

56

Although regions in the hypothalamus have a large role in regulating eating behavior, there is not just one hunger center in the brain, nor is there just one neurochemical that controls appetite and satiety.

57

Eating is a complex process that involves not only the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), but the peripheral nervous system as well—the portion of the nervous system that extends to all parts of the body. There is a growing list of nervous system processes and neurochemicals that play a role in regulating eating.

58

Because of this, eating behavior is not simply explained, and to try to do so with precise accuracy on a brain map would be overstepping what is currently known in neuroscience. To say exactly where urges to binge arise in the animal brain would be oversimplification and speculation that is not currently supported by brain research. The brain, in general and in relation to eating disorders, has yet to be completely explored and explained, and it won't be completely explored and explained anytime soon.

59

However, this complexity and our incomplete understanding of the brain and nervous system as it relates to eating behavior does not mean we can't work to find solutions. As it relates to finding treatments for eating disorders, "[a] suitable understanding of a mere fraction of the complex equation may be sufficient to permit a novel and effective clinical approach to the problem."

60

This is where I humbly try to interject my ideas—not presenting them as unequivocal scientific facts, supported by countless studies, but as useful concepts, based on sound theories and research—that helped me escape bulimia. Just understanding a fraction of my brain's function allowed me to recover quicker than I ever thought possible, and to share my eating disorder and recovery story only requires me to explain that fraction—in simple terms.

We can make progress in treating eating disorders even if we don't have a precise explanation of how the brain and nervous system organize behaviors.

61

I believe I have made progress, if only in understanding my own problem—or a fraction of my own problem. So, as I discuss the survival instincts and the hypothalamus here (and later on, the neural pathways of habit), I know there are limitations, but that does not prevent using what information we can to our advantage.

MY EXPERIENCE WITH SURVIVAL INSTINCTS

The animal brain—and specifically the hypothalamus located there—is focused on survival. The behaviors directed by this area of the brain are "less easily modified than the more deliberately planned, finely tuned responses generated in the newly acquired cerebral cortex above it."

62

Behavior directed by the hypothalamus and the animal brain as a whole is much like the behavior of animals that do not rationalize before acting, like the behavior of the binge eating rats.

I felt my survival instincts fully when I tried to diet, and the more I tried to restrict food, the more I wanted to eat. My survival drives led to exactly the opposite of what I wanted from my diet: they made me want to eat more than I ever had before I dieted. That was merely my animal brain's way of protecting me. Since I didn't understand my survival instincts, I thought I was crazy for craving food as much as I did. I thought I was cursed with an insatiable appetite that I had to keep a tight harness on at all times. So I planned my meals very carefully and took extra care to avoid certain foods and situations that tempted me. This wasn't me symbolically trying to control my life by controlling my food intake, or me trying to distract myself from other problems by turning my attention to food, as I learned in therapy; it was me attempting to restrain my survival instincts.

There was nothing abnormal about my strong cravings for food. My animal brain was only doing its job—the same job it's done for millions of years. Thousands of years ago, a strong appetite during times of famine served an important purpose. It drove our ancestors to hunt and capture food, and to consume as much as possible to build up caloric reserves. The problem today is that we are still wired to protect ourselves when food is scarce, but food isn't truly scarce for most of us who live in wealthy nations.