Brazzaville Beach (20 page)

Authors: William Boyd

She gave him two. The plastic capsules were yellow and white.

“You and your damn pills,” she said with a resigned grin.

“See? Sometimes they come in handy.”

He swallowed the pills and pulled up the blankets to his ears. She crouched by the bed and stroked his wiry hair. She kissed him, reassured him, and made brief plans about his coming down to Knap to rest. Soon he began to drift away.

“We'll be OK,” he said loosely. “We'll work it out.”

She switched off the light, closed the door and went back to the sitting room. She locked the Librium and sleeping pills in a drawer of the bureau and made herself a strong scotch and soda. She sat down at the table and began to repack his briefcase. She was weary herself, aching-limbed, but with an odd background sensation of restlessness.

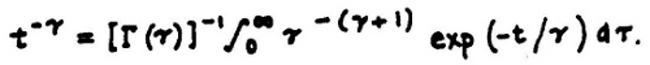

Her eyes fell on the untidy clutter of John's papers and printouts. Strange jottings and diagrams, scribbled calculations. Amongst the detritus she counted two napkins, a cardboard lid from a cigarette pack and the torn-off cover of a Penguin book. She looked at the crabbed, tiny figures: to think that someone can read this stuff, she thought, picking up loose papers, actually make sense of these numbers and squigglesâ¦. She shook her head, ruefully. This was the magic she was in awe of, she had to admit, the runic language of the mathematician. It was uncanny, otherworldly. She picked up a scrap of paper torn from a memo

pad. There were some words written on itâ

Euler's gamma functn. def

.âand below that:

What kind of bizarre and extraordinary mind dealt in this type of discourse, used these symbols to communicate crucial ideas?â¦Idly, she turned the sheet over. There was another scribbled note here, not in John's handwriting:

Darling J

,

Come at four. He goes off to Birmingham for

three

(!) days, from tomorrow. Can you stay a night? Please try. Please, please.

XXXXXXX

THE ONE BIG AXIOM

On Brazzaville Beach the time passes slowly, easily. On the days when I am not working I eat my meals, swim, read, walk, sketch, write. The day does not hurry by. The view is familiar, the seasonal changes, negligible. Brazzaville Beach during the rains is little altered. The palms are there, the casuarina pinesâ¦the waves roll in. This is my time, personal and private. Whatever is going on out there in the world, with its hurry and its business, is something else. Its progress is marked by time, too, by clocks and calendarsâcivil timeâbut on the beach the days move by to the tick of a different clock

.

Civil time, as the chronologists call it, has always been based on the rotation of the earth. But our sense of “private” time is innate. Neurologists think that this sense of time, which is always of the present moment, is conditioned by our nervous systems. As we grow older, our nervous systems decelerate and our sense of personal time dawdles correspondingly. But civil time, of course, tramps on remorselessly, its divisions

constant and inexorable. This is why our lives seem to pass more quickly as we age

.

So I try to ignore civil time on Brazzaville Beach and instead measure my days by the clocklike systems in my own body, whatever they are. I am pleased with this idea: if I can ignore civil time as I age, and as my nervous system slows, the sense of the passing of my life will become ever more attenuated. I wonder, fancifully, if I have a notion here that I could call the Clearwater Paradoxâafter Zeno'sâwith me, as Achilles, always slowing down, never quite able to catch the tortoise of my death, no matter how close I come

.

No. There is one thing we can be sure ofâthe one big axiom: when my nervous system shuts down entirely, and it will, my personal time will end

.

Â

I dived in and swam a couple of strokes underwater, enjoying the moment of coldness and the silence. I kept my eyes closed because of the chlorine, opening them after I had surfaced, then turning on my back and swimming a slow backstroke to the shallow end. As I swam I saw Hauser climbing up to the top of the three-tier diving board. He was wearing very small cerise swimming trunks, almost invisible beneath the solid tureen that was his belly. He stood at the end of the board, rose on tiptoes and pretended to dive. I heard the faint jeers of the others and some slow, ironic handclapping. Hauser bowed elaborately and climbed down.

My hand touched the end of the pool and I stood up. I smoothed my hair back with my hands and wrung the long hank dry behind my neck. As I did so, Toshiro, who was sitting on the edge, his feet dangling in the water, looked candidly at my breasts. I looked back at his, equally candidly. I had always imagined Toshiro to be fit and muscled, but his torso was soft and pudgy, like an adolescent boy with puppy fat, his breasts pert cones with brown nipples.

“Why don't you jump in?” I said.

“I can't swim.”

I waded over to the steps. “Do you want me to teach you? After lunch?”

He looked surprised. “Wellâ¦yes, please. Can you?”

“We can make a start. It's ridiculous a man of your age not being able to swim.”

I climbed out. Hauser, who had been the dummy hand, had rejoined the bridge game. Mallabar, Ginga and Roberta were staring at the spread fans of their cards. Some way off, Ian Vail sat in the shade of an umbrella reading a paperback. I returned to my lounger and dried myself down.

We were on our “works outing,” as Mallabar had whimsically christened this trip. We had traveled fifty miles from the camp to the Nova Santos Intercontinental Hotel. The Nova Santos was only half completed when the civil war had begun, and further work had been abandoned since then. It was designed to be a luxury hotel, with five hundred bedrooms, olympic swimming pool, tennis courts and an eighteen-hole golf course, the first and most important symbol of the country's rejuvenated tourist industry. Now it stood, a new ruin, waiting for the end of the war and for new funds to be available, a sad reminder of what might have been.

The hotel was positioned on a small hill and looked out, over a view of monotonous orchard bush, northward to the dusty, distant slopes of the Grosso Arvore escarpment. The curving drive up to the entrance portico had been built, as had the portico itself, the lobby and reception area, and, mysteriously, the swimming pool. Everything else remained in the state it had reached when the money had run out. From my lounger, I could see the gray concrete bricks and the rickety bamboo scaffolding of a half-finished residential block. Already vines and creepers had climbed high up the three-story sides, and plants and weeds grew as high as the ground-floor window ledges. The area cleared for the tennis courts had been planted with cassava and yams by the families of the skeleton staff who remained behind, and the golf course consisted of a few sunbleached, termite-gnawed, black-and-white stakes hammered into the ground here and there. But the power lines that had been run out to the hotel from the national grid had never been dismantled, and the Ministry of Tourism paid the staff and kept the pool functioning, waiting for better days. The thick teak slab of the reception desk was burnished and gleaming with polish, and the cool terrazzo floors of the lobby were regularly

mopped down and free of dust. One could even order a drink, as long as it was beer.

Mallabar had announced a few days previously that we were to visit the Nova Santos. This was something he had treated the team to periodically whenever he felt we could benefit from a day off and a complete change of scene. We had set off on the two-hour drive in good spirits, transported to the hotel in two Land-Roversâthe project members crammed into one, the cooks and the barbecue gear in the other.

I could smell charcoal smoke now, as I lay in the sun. It made me hungry. I sat up and sipped at my beer, looking round at my colleagues. It was odd to see them all in their swimming suitsâon vacation, as it were. These familiar people were, in their almost nakedness, made strange to me to me again. Apart from Hauser, of course. However repugnant his cerise thong might be it was a relief not to have to look at what it concealed. Mallabar wore absurdly boyish sawn-off jeans. He was lean and tanned (where and when did he sunbathe?) with a curious two-inch-wide stripe of hair running vertically from throat to navel. By contrast, Roberta was almost unnaturally pale. Her skin was milk white, with a subcutaneous blueness about it. She wore an old-fashioned, two-piece swimsuitâwide shorts and a top with a flap hanging down from it like a fixed curtain, that exposed only two inches of creamy, plump midriff. Her breasts were large and mobile. She appeared quite unself-conscious of the amount of cleavage she had on show. It was Ian who seemed embarrassed for her. He had been moody and taciturn all day, and had not even bothered to change into his swimsuit. He sat in the shade, wearing shorts and a T-shirt, some distance away, reading intently. He hated sunbathing, he had said, and the heavily chlorinated water irritated some skin complaint he suffered from.

Ginga wore a minute, pea-green bikini. She was very thin, almost emaciatedly so; the twin triangles of her top appeared creased and empty. I noticed the luxuriant hair in her armpits, dense brown divots, and the tiny scrap of material over her groin could not hope to conceal the spreading scribble of pubis that underflowed onto her inner thigh. I knew that Ginga did not care: on the journey to the hotel, she had reminisced enthusiastically

about the nude beaches on the Isle de Lerins off Cannes where she and Mallabar had spent some summer holidays in their early married life. The bikini was no more than a gesture to propriety.

And me? What was Dr. Hope Clearwater wearing? I had chosen carefully. I was the earnest head girl, the keen captain of the school swimming team, in an opaque black one-piece thatâI trustedâgave absolutely nothing away.

Â

The weather was fine, just a faint haze obscuring the perfect blue of the sky. We lounged around; the bridge game came to an end; we ate lunch. We had grilled chicken and some big, freshwater prawns, fried plantain and baked sweet potatoes, a huge tomato and onion salad and some rare lettuce. Plenty of fruit and plenty of beer.

After lunch there was more sunbathing. As promised, I tried to teach Toshiro to swim but he refused to put his head underwater, so I gave up after ten minutes.

I returned to my book but was distracted by the sight of Mallabar oiling himself. I had never seen anyone oil himself so fastidiously. He oiled every visible inch of his body: he oiled the crevices of his toes and the backs of his hands. Then he asked Ginga to oil his back but she said noâshe was reading and didn't want her hands to get greasy.

“Ask Roberta. Ask Hope,” she said.

Mallabar turned to look at me, eyebrows raised, questioningly. He read my answer in my expression and called out to Roberta instead.

“Roberta? Could you do me a favor?”

No one's back was ever oiled with such lingering diligence. Mallabar lay face down on his towel, eyes closed, while pale, plump Roberta crouched over him as she massaged the lotion in, to and fro, to and fro.

I walked over to Ian Vail, still under his umbrella, still reading. Half a dozen empty beer bottles stood on a low table beside him. I sat down on the end of his lounger. He drew his feet up to give me more room.

“Hi,” he said.

“How're things?”

“Fine. What about you?”

“Fine. In fact I've quite enjoyed myself.”

“So've Iâgetting mildly pissed on weak beer.” He held up his paperback. “Have you read this?”

“No. After you.”

“It's not bad.”

“Talking about books⦔ I paused. “How's Roberta getting on with Eugene's?”

“Nearly finished, I think.”

“Have you read it?”

He colored slightly. “No. I'm not allowed to. Eugene prefers it that way. And you know Roberta⦔

“Sure. No, I suppose I can understand that.” I wondered if he had seen her oiling the master, her white hands smoothing Mallabar's brown back.

I looked away and watched Hauser pad doggedly across the concrete toward the diving board. You've done that trick already, I said to myself; we're not going to find it quite so amusing second time around.

“What do you think,” Ian Vail said, lazily querying, “what do you think our chimps will be doing today, now that we're not there to observe them?”

I nearly told him, almost a reflex answer to an idle question: killing each other. But I checked myself. Hauser had reached the topmost diving board and he stalked to its end, chest inflated, every inch the champion, and spread his arms wide.

“Oh no, not again,” I said wearily. Then, to Vail. “See you later.”

I strolled back to my seat, my eyes on Hauser and his pantomime.

Hauser leapt out into space, almost swooped, in a perfect butterfly dive, horizontal for an instant, thenâin a kind of midair checkâhis arms came together, his head dipped, and, with a precise and practiced effort, he hitched his tubby legs into a vertical plane and sliced cleanly into the water with hardly any splash. Bubbles seethed.