Bread Matters (29 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

A final thought on crusts. Despite my dismissive remarks about baguette crusts and the rather daft advice (like putting ice in the oven) offered even in serious baking books to create this sort of effect, I don’t deny that there are few sights more gratifying than a loaf of bread with a shiny crust crackling and splitting as it cools. Rather than messing about trying to trap enough steam in a domestic oven, you might like to try the cloche method.

This involves covering your bread with an upturned ceramic bowl (earthenware, stoneware or ovenproof glass) as it bakes. The idea is that moisture escaping from the dough re-condenses on the surface of the dough and causes a partial gelatinisation of the starch, which eventually solidifies as a thin, crisp, shiny crust.

A further effect of baking under a bowl is that it takes longer for the oven heat to penetrate the dough, so the yeast survives longer in the oven and, in a dough with the gluten strength to take it, expands the whole structure more than it would under normal conditions.

Some trial and error is required if you attempt this with whatever large bowl you have to hand, rather than shelling out a large sum for a purpose-made earthenware cloche. I suggest preheating your bowl as you would a baking tile, in order to minimise the drop in oven heat when you insert your bowl-covered loaf. You may find that you can keep the bowl on all through baking but, if the top crust remains rather pale, remove the bowl for the last half of baking; all the good work as far as crust formation is concerned will have been done by that time.

CHAPTER TEN SWEET BREADS AND CELEBRATIONS

‘All lovely things are also necessary.’

JOHN RUSKIN

,

Unto This Last

(1860)

Bread is sustenance, comfort, celebration and sacrament. It can be each and all of these when at its plainest. But every bread-eating culture has demonstrated an urge to enhance the specialness of bread through some form of enrichment or embellishment. It could be the simple addition of fat and sweetness before a period of fasting or the intricate decoration of the centrepiece for some important occasion. In making something special out of the everyday, people link simple gratitude for having enough to eat with a more profound sense of connectedness with the community and the natural world that sustains it.

Making festive breads is easy and rewarding. A special dish or meal seems much more memorable if you have made it yourself rather than warmed up something from a shop. The hot cross buns that you make a day or two before Easter are a gift and a link with a tradition whose meaning is another casualty of the supermarkets’ assault on the seasons.

You have probably got most of the ingredients for special breads in your kitchen already: eggs, sugar, fat, spice, fruit, nuts, maybe some alcohol. Using them to turn plain dough into something exceptional is pretty straightforward. Here are a few principles and recipes.

Basic Sweet Bun Dough

This is a simple recipe, which can either be made into plain sweet buns or teacakes or used as the basis for more elaborate buns or loaves with the addition of nuts, spices and exotic fruits.

Yeast cannot feed on ingredients like fat, egg and spice, so it is a good idea to get it working vigorously before mixing it with these things. That is the purpose of the ‘ferment’ – a mixture of flour, yeast, liquid and a little sugar that is made before the main dough.

The ferment

20g Sugar

10g Fresh yeast

280g Milk (at about 32°C)

140g Stoneground wholemeal flour

450g Total

This is a very liquid ferment, so dissolve the sugar and yeast in the milk, then make a paste by adding some of this mixture to the flour. Gradually add the rest of the milk, whisking the mix until it is smooth and creamy. If some lumps remain, don’t worry. They will disappear when you knead the main dough. Leave the ferment covered in a warm place until it has risen to its full extent and then ‘dropped’. This should take about an hour, depending on the temperature.

Bun dough

450g Ferment (from above)

200g Strong white flour

110g Stoneground wholemeal flour

50g Butter

35g Sugar

50g Egg (1 egg)

5g Sea salt

900g Total

To make a plain dough, mix all the ingredients together and knead until the gluten structure is well developed. This dough should be very soft. Indeed, at the end of kneading, it should still be difficult to stop it sticking to your hands. If you add flour to tighten it up, it will make kneading easier, for sure. But the end result will be rather solid buns or loaves.

If you are going to make this into a spiced dough, stir the spices into the flour before adding the rest of the ingredients. If fruit or nuts are to be used, they should be folded in towards the end of the kneading process. Add them too soon and they interfere with the formation of a good gluten structure during kneading, and there is a risk that the fruits will become smeared through the dough in an unsightly manner.

Return the dough to the bowl, cover it and allow it at least an hour to rise. It should grow in size appreciably before you take it to the next stage. This might be simply to form buns or loaves, or you may wish to enrich it further with nuts, fruit etc.

Hot Cross Buns

In medieval days it was common for bakers to place a cross on their loaves, perhaps to repel any evil spirits that might infect the bread and prevent it rising. After the Reformation, such practices were frowned on as ‘popish’, but the cross remained as the symbol for the Easter bun.

Rich, spicy, fruited doughs were allowed at holidays or public burials and by the seventeenth century the hot cross bun was established fare for Maundy Thursday. Until quite recently, people ate hot cross buns on just this one day of the year. Needless to say, supermarket culture has diluted such seasonal pleasure and hot cross buns now appear on shelves almost before Christmas is over, if not all year round. However, perhaps the supermarkets have learned from baking history, for what is ‘One a penny, two a penny’ if not the original ‘buy one, get one free’?

Makes 16 hot cross buns

Fruit mix

180g Sultanas

80g Raisins

40g Water (hot) or other liquid (e.g. fruit juice or port)

300g Total

Soaking the fruit is not essential; indeed some baking authorities insist that it should merely be washed and dried. However, dried fruit tends to absorb moisture from the dough, so plumping it up first with some liquid makes for a more succulent and longer-lasting bun.

Put the fruit in a strong polythene bag and pour on the water or other liquid. Seal the bag and shake it so that all the fruit is covered in liquid. Leave this for at least an hour, but preferably much longer, giving the bag an occasional shake if you remember. For even tastier buns, use fruit juice or a sweet alcoholic drink like port.

Hot cross bun dough

900g Basic Sweet Bun Dough (from above)

10g Ground mixed spice (to be included in the basic dough)

300g Fruit Mix (from above)

1210g Total

As mentioned above, add the spice to the dough ingredients before mixing. The best time to add the fruit is about 10 minutes after you have finished kneading. The dough’s gluten will have relaxed a little, making it easier to work the fruit in. Drain any excess liquid off the fruit first, otherwise the dough may become unmanageably soft. Either in the bowl or on the table, add the fruit to the dough and gently fold and press until it is fairly evenly dispersed. If you are using a mixer, use the slowest possible speed and keep a watchful eye on the dough. The danger is that excessive force, of either hand or machine, will break the dough up into a sticky mess and smear the fragile fruit into brown streaks. It is better to stop folding sooner rather than later, even if the fruit seems rather unevenly spread. The act of moulding buns or loaves later will help to disperse it. The amount of fruit given in the recipe may seem rather large at this point, but it is surprising how it thins out once the buns have expanded and been baked. Cover the fruited dough and leave it to complete its first rise.

To make buns (crossed or not) weigh the dough out into 16 pieces of about 75g each, placing them on a lightly floured area of worktop. If some gas remains in the dough as you do this, so much the better: it will make shaping easier. Mould the pieces up into fairly tight rounds, dusting your hands, but not the worktop, with a little flour if the dough shows a tendency to stick. Place the rolls in straight lines about 5cm apart on a baking tray lined with baking parchment. Cover them loosely with a polythene bag and put them in a warm place to prove until they are almost touching.

If you want your buns plain, simply put them in an oven preheated to 180°C. They will go quite brown on account of the added sugar in the dough. Check them after 15 minutes and try to remove them from the oven when they are just done.

If you want to put crosses on your buns, don’t do what I did for my first ever batch, i.e. roll out very thin strips of white pastry and laboriously lay them on. Piping a runny dough mix (see below) with a fairly fine nozzle is so much easier and a lot more fun. If you don’t possess a piping bag, use a reasonably thick polythene bag. Gather the mixture into one corner, screwing up the rest of the bag behind it to avoid leaks. Then cut a very small piece off the corner of the bag to allow the crossing mix to flow. Test the rate of flow and the width of the trail and enlarge the hole if necessary. Ideally, the trail of crossing mix should be no more than 5mm wide as it comes out of the bag. It will spread a little as it settles on to the buns.

Crossing mix

50g Plain white flour

1g Baking powder

5g Vegetable oil

50g Water (cool)

106g Total

Bake the buns as soon as you have finished crossing them. If you leave them for any length of time, the crossing mix will tend to flow out too wide and thin.

The ideal hot cross bun has a clear contrast between the dark brown bun surface and the white crosses. If you bake them in too hot an oven or for too long, the crosses will also go brown and will be less distinct. If the oven is too cool, you will have to leave the buns in for so long that the crosses will bake into the same biscuity colour as the rest of the dough. So some trial and error may be necessary to get the right oven temperature and baking time.

If you consistently have trouble getting a good contrast between the bun surface and the crosses, try egg-washing the buns immediately after they are moulded up. The egg will thin out as the buns expand and its effect will be to accentuate the brown colour of the parts of the dough surface not covered with crossing mix.

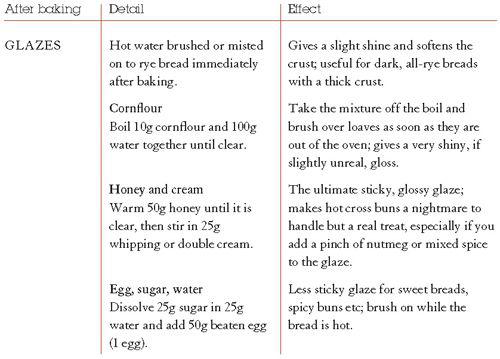

When the buns, crossed or not, come out of the oven, brush them generously with a sweet, spicy glaze. My favourite is the honey and cream glaze described on page 249.

Bun Loaf

The Hot Cross Bun Dough can also be baked as a loaf. Divide it between 2 greased small loaf tins. Mould up as for a normal loaf. Prove and bake in a moderate oven of around 180°C.

A nice addition to the bun loaf is provided by nibbed roasted hazelnuts or other small pieces of nut. Have the nuts in a shallow bowl or tray and dip each moulded loaf thoroughly in them before putting it in its tin. The dough surface must be moist and tacky in order to get a generous and even covering of nuts.

Glaze a plain loaf after baking but leave the nut-covered one as it is.

European festival breads

In the past, the enrichment of bread with sweetness, fat and egg was often associated with special times of year, notably the major religious festivals. People would also put relatively scarce and valuable extra ingredients into bread either before or after a period of fasting. When you compare various festive baking traditions, there is really very little difference in the basic recipes, which is not surprising – after all, there were not that many different ingredients available. It is shape and decoration that distinguish one national or religious tradition from another. Special loaves often illustrate or represent one or more significant aspect of a culture’s history or pattern of observance. The Jewish plaited challah is a prime example; its many strands may represent the tribes of Israel and the braided structure allows the baked loaf to be broken easily by hand, thus obeying a prohibition against using a cutting knife on the Sabbath.

There is so little difference in the recipes for a bunch of European festive breads that I have arrived at a common dough which can be used as the basis for panettone,

colomba pasquale

(Italian Easter bread), stollen, kulich,

christopsomo

(Greek Christmas bread) and so on. I give the full recipes for stollen, the very popular German Christmas bread, and kulich, the Russian yeast cake eaten at Easter with its delicious cream cheese accompaniment, paskha.