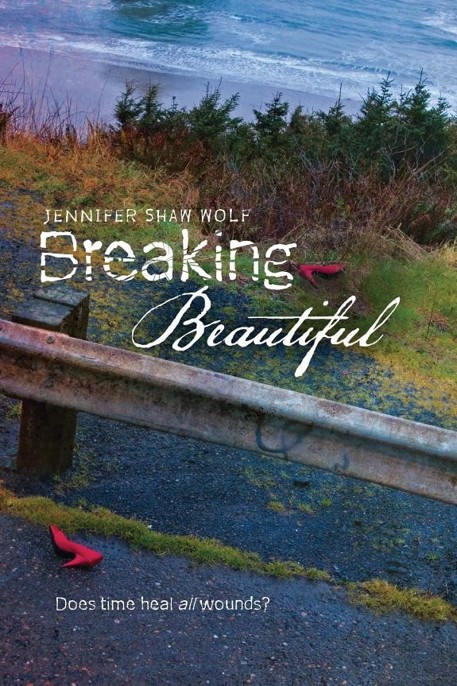

Breaking Beautiful

Read Breaking Beautiful Online

Authors: Jennifer Shaw Wolf

Breaking

Beautiful

JENNIFER SHAW WOLF

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Acknowledgments

Imprint

For David, for showing me the power of true love

For Jason, who taught me that the strength of your

spirit cannot be bound by the limitations of your body

The clock says 6:45, even though it’s really 6:25. If everything were normal, the alarm would ring in five minutes. I’d hit the snooze button, wrap Grandma’s quilt around me, and go back to sleep until Mom came in and forced me to get up. I used to stay in bed until the last possible minute and then dash around getting ready for school—looking for my shoes or a clean T-shirt, and finally running out the door to the sound of my boyfriend, Trip, laying on the horn of his black 1967 Chevy pickup.

Nothing is normal, and no one makes me go to school.

Mom comes in and stands at the door to see if I’m awake.

I’m always awake.

“You think you can handle school today, Allie?” Mom’s quiet, so if I am asleep I can stay asleep. I shake my head without rolling over. She hovers for a minute or two, so I can see her concern before she leaves to get ready for her orderly world.

Andrew is next, twin telepathy guiding him to my door. He knows or at least senses more than anyone how much I’m hurting. I know he does, because until now it’s been me on the other side, watching him hurt. You can’t share a womb with someone for nearly seven months without creating an unbreakable bond.

His wheelchair hums and bumps against the wall. Our house is small, one level, and old. Perfect for Andrew. The hallways and doors are wide enough for him to maneuver his chair.

A tap at my door, barely audible. A thump against the wall. He grasps and then loses his grip on my door handle. When we moved in, Dad changed all of the doorknobs to long handles so Andrew can open the doors, but it’s still hard for him. I should get up and help him, but my body feels like lead.

The latch clicks, and his chair pushes against the door. He moves forward until the door opens enough for him to see my bed. I roll over so I can see him, but he stays in the doorway. That’s new, the invisible wall between us, a barrier at the threshold of my room that he never crosses anymore. He breathes hard and speaks in his halting voice that almost no one outside our family can understand. “Okay, today, Al? School?” Andrew is smart—brilliant—but most people think he’s mentally retarded because of his body and the way he talks.

Andrew has cerebral palsy, brought on by a lack of oxygen when we were born—eight and a half weeks early. I came out screaming like a full-term baby. He was cold and blue. His body is twisted and barely in control, but his mind is sharp. His injuries from our birth are easy to see. Mine are less obvious.

I shake my head and avoid Andrew’s eyes, but I’m drawn

there. His eyes are soft, brown, and deep. The pain I see there, pain for me, makes me look away.

“You … should.” He licks his lips and his bad hand shakes. He forces a smile. “I could …” He’s trying so hard to talk, so hard to convince me to get out of bed. For his sake, I wish I could get up.

I burrow deeper into the quilt, worn flannel patches my only protection from everything I’m not willing to face. “I just”—don’t look him in the eye—“I can’t.” The waver in my voice matches his. “Not yet.”

He lingers. I close my eyes so I don’t have to see his face.

“Andrew, breakfast.” Mom’s voice floats from the kitchen. Andrew’s chair whirs down the hall. The red numbers slide by on my clock. Morning sounds float muffled through the walls and into my room. Dishes clink, the sink turns on and off. Dad tromps across the kitchen floor. Mom helps Andrew with breakfast. His bus pulls up out front.

Our house is so small you can hear everything that everyone does or says. Not a good place for keeping secrets. Even the outside walls are thin. The parade of life going by sounds so close it could be marching through my bedroom. Grade-school kids laugh. Another bus hisses to a stop. A motorcycle roars by; Trip’s friend Randall, probably with Angie Simmons glued to his back. If I sat up and opened the blinds, I could watch the whole thing from my bed like some reality TV show—a reality I’ve never belonged to.

How can they keep going like everything is normal?

The days have started to run together, but I think it’s the fifth day of school, the second week of what would be my

senior year. Over a month since the accident and three weeks since I came home from the hospital. There’s an untouched pile of schoolbooks and papers in the corner by my desk. Blake brings my homework by every day—at 3:08—part of my new routine.

I slide out of bed because Andrew didn’t close the door all the way. The outside air coming in around the edge makes me feel exposed. I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror over my dresser when I stand up. Wounded, scarred. Ugly. I can’t even look at myself. I’m glad Trip can’t see me like this.

He would hate my hair.

Trip never wanted me to cut it, not even just a trim. Before the accident it hung—long and thick and gold—to the middle of my back. I run my hand through what’s left. It still surprises me how soon I reach emptiness. They shaved a swatch a couple of inches wide and almost six inches long across the back of my head, but someone in the hospital took pity on my blond locks. They left enough length to cover the gash. For a while I had a morbid, half-bald, punk ponytail to go with the Frankenstein stitches across the back of my head and over my right eye. When I came home, Mom’s friend layered it into a sort of bob that brushes against my neck and sort of covers the bald spot. It looks horrible.

I touch the wound that’s morphing into a scar on the back of my head. Coarse new hair pokes through where the stitches used to be. It itches. I guess that means it’s healing.

Trip’s eyes follow me to the door. Bits of our relationship are mounted on every wall and rest on every flat surface of my room. Pictures of us together are lined up on shelves and stuck

in the corner of my mirror—prom, homecoming, us just goofing off.

Only the last one, the one from the cotillion, the last picture ever taken of Trip, is missing. I put it on the top shelf of my hutch—the shelf I need a chair to reach. I shoved it there without even looking at it. Trip’s parents gave it to Mom after the memorial service because I was still in the hospital. Memorial service—I guess you can’t have a real funeral without a body.

I reach to shut the door but hesitate when I hear Mom and Dad talking in the kitchen. I’m still not used to hearing Dad’s voice. He was deployed for almost eighteen months and then back and forth between here and Fort Lewis for the last six. Now that he’s retired from the Army, he’s been trying to get his auto shop going. His being home this late is a bad sign—no appointments and no cars to work on in the shop. He’s a really good mechanic, but business hasn’t picked up yet because everyone in town is loyal to Barney’s Auto Shop. Dad says that Barney’s is a rip-off, but they’ve been the only shop in town for like forty years.

“The guys at the café were talking yesterday,” Dad says. A chair scrapes against the wood floor. “I guess there’s a new cop at the police station.” At least they’re talking about something other than me. Dad isn’t a coddler. Twenty years in the Army made him tough. He harps on Mom to make me get up, go to school—get on with my life.

“Oh?” Mom sounds amused. “How long do you suppose this one will last?” Pacific Cliffs is a small town, one of those places where everyone knows everyone and no one locks their doors at night. The long arm of the law is Police Chief Jerry

Milton—Mom’s date to junior prom. Chief Milton by himself has always been sufficient police for Pacific Cliffs, until now.