Breaking Stalin's Nose (8 page)

Read Breaking Stalin's Nose Online

Authors: Eugene Yelchin

THEY ARE DRUMMING and bugling and singing in the darkened hallway. “A Bright Future Is Open to Us

.

” I know every word, but this time I don't sing as I watch the future Pioneers march away, melting into the brilliant lights of the main hall. Alone now, I heave the banner over my shoulder and listen for the drumroll, my cue to follow.

.

” I know every word, but this time I don't sing as I watch the future Pioneers march away, melting into the brilliant lights of the main hall. Alone now, I heave the banner over my shoulder and listen for the drumroll, my cue to follow.

I have waited for this moment all my life. I wanted it so badly. I would imagine myself marching into the main hall, beaming with pride, all eyes upon me. Then I'd see myself standing on a podium beneath the huge face of Stalin, eager for my turn to

have the Pioneers scarf tied around my neck. How happy I felt when my dad told me he would tie my scarf. I could see it: He'd step up to me, lay the scarf across my shoulders, tie the knot as the rule saysâthe right tip extending lower than the leftâthen would call to me in his strong but kind voice, “Young Pioneer! Ready to fight for the cause of the Communist Party and Comrade Stalin?”

have the Pioneers scarf tied around my neck. How happy I felt when my dad told me he would tie my scarf. I could see it: He'd step up to me, lay the scarf across my shoulders, tie the knot as the rule saysâthe right tip extending lower than the leftâthen would call to me in his strong but kind voice, “Young Pioneer! Ready to fight for the cause of the Communist Party and Comrade Stalin?”

I set the banner down and lean it against the wall. I need my hands to dry my eyes, which are filling with tears. Right then, I hear the drumroll. It throbs and breaks off. It's my turn.

I think of everybody in the main hall listening to the drumroll again and again, eyeing the entrance through which I am to enter, wondering what's holding me up. I see their facesâthe kids', the teachers', the janitor Matveich's, the cleaning lady Agafia's, Principal Sergei Ivanych's, and, next to the podium, that of the State Security senior lieutenant who has replaced my dad as guest of honor. My

dad, who is in prison. My dad, who said last night, “Tomorrow's a big day.” He was right. It was a big day. It changed my life forever.

dad, who is in prison. My dad, who said last night, “Tomorrow's a big day.” He was right. It was a big day. It changed my life forever.

I take a last look at the banner, turn away, and dash out the back door, down the stairs, and out of the school. I don't want to be a Pioneer.

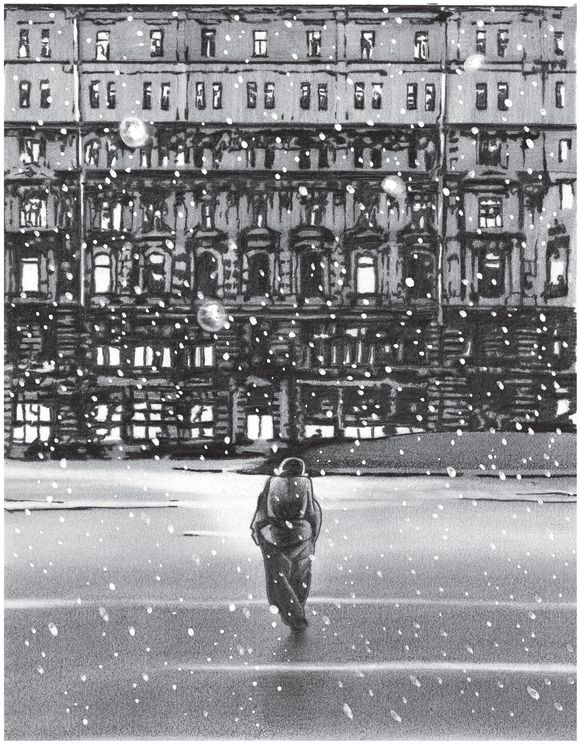

THIS STREETCAR is like an ice cave. The frost inside the glass makes the windows glow white. I lean in and breathe on the glass. A small circle opens like a peephole in a prison cell's door. I see shiny black automobiles tear through the snow toward a giant yellow building. Somewhere in that building, my dad is in prison.

“Lubyanka Square!” cries the conductor. The streetcar screeches to a stop and the ice-crusted doors begin to part. I squeeze out and hop off and cross the square.

“Step back!” barks the guard, yanking the rifle off his shoulder. I keep going, so he aims the rifle at me. He looks like he'd shoot a kid, so I stop.

“My dad is in prison here,” I say. “I need to see him.”

Keeping me in his gun sights, the guard nods toward the edge of the building.

“Around the corner?” I say.

He nods again.

What I see when I round the corner, I don't expect. It's a line of people who must be waiting to see prisoners. The line runs along the building and across the street and down the next street and up the next one, and by the time I reach the end, I pass thousands of people waiting. I get in line.

After a while, a woman in front of me turns around. “You must be cold,” she says. “Where are your warm things?”

I shrug. She stares at me for a moment, then digs into her bag and pulls out a woolen scarf. “I made this for my son,” she says. “Wrap it around. I'll take it back when we get to the door.”

I wrap the scarf around my neck and ears and she helps me with it. Her scarf is warm.

“Both of your parents in there?”

I shake my head. “My dad.”

“Where's your mom?”

“She died. In the hospital,” I quickly explain.

She looks at me sadly, and I say, “My dad didn't take me to the funeral. I still have to ask him why.”

“Funerals are sad,” she says.

That's when I know why he didn't take me. He didn't want me to be sad.

“What about relatives? Uncles? Aunts?”

I think about Aunt Larisa and say, “No. Don't have any.”

“Where do you live?”

I shrug again.

“Homeless,” she says, and shakes her head. “Good thing you won't need a bed for the next three nights. That's how long it'll take you to see your dad.”

I don't mind. I have nowhere else to go. She doesn't even ask if I'm hungry, just takes out something wrapped in a cloth and hands it to me. I unwrap itâa baked potato, still hot. She stares at me while I eat it.

“What's your name?” she says.

“Sasha Zaichik.”

“I tell you what, Sasha Zaichik. Now that my son's cot is empty, you're welcome to it if you want.”

I look up at her and see that she's smiling. Her smile is kind and natural.

I should ask my dad, I think, but instead I say, “Sounds good. Thank you.”

She nods, then looks up at the low sky. It's snowing again.

“What a mess we got ourselves into, huh, Zaichik? Think we can sort it out one day?”

I don't know.

“We will,” she says. “But for now, we have a lot of waiting to do. So let's wait, Zaichik.”

And we do.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

THE END

An official from the Committee of State Security once called me in for an “informal” chat. A typical Soviet secret policeman, he locked the door of his office, put the key in his pocket, and invited me to discuss the political views of my coworkers. His goal was to recruit me as an informer. I had no idea what would happen to my family or to me were I to refuse, but I suspected bad things. The State Security terrified everyone, and I was afraid. But I could never become a snitch, either. For two straight hours, I played dumb, evading questions and pretending I didn't understand him. He got bored, unlocked the door, and finally let me go. I felt insulted and humiliated, but I was not harmed. Had that happened some years earlier, when the ruthless dictator

Joseph Stalin ruled Russia, I would not have gotten out of that office alive.

Joseph Stalin ruled Russia, I would not have gotten out of that office alive.

During his reign, from 1923 to 1953, Joseph Stalin ensured his absolute power by waging war against the Russian people. Stalin's State Security executed, imprisoned, or exiled over twenty million people. Not a single person, be it a government official, war hero, worker, teacher, or homemaker, could be certain he or she would not be arrested.

To arrest so many innocent people, crimes had to be invented. Stalin's propaganda machine deceived ordinary people into believing that countless spies and terrorists threatened their security. Tormented by fear, Soviet citizens clung to Stalin for guidance and protection, and soon his popularity reached cult status. “The father of all Soviet children” smiled and waved at his supporters during parades and celebrations, while at night, in his Kremlin office, he was signing orders for innocent people to be shot without trial.

Paradoxically, when I was growing up in the 1960s Soviet Union, few people of my generation were aware of what had transpired under Stalin. During his lifetime, the crimes had been carried out in absolute secrecy. After

his death, the secrecy continued: All evidence was classified or destroyed. Older generations, either still terrified or responsible for the crimes, kept silent.

his death, the secrecy continued: All evidence was classified or destroyed. Older generations, either still terrified or responsible for the crimes, kept silent.

But Stalin could not simply disappear; his legacy endured in the Russian people. They had lived in fear for so long that fear had become an integral part of their very beings. Unchecked, fear was passed on from generation to generation. It has been passed on to me, as well.

This book is my attempt to expose and confront that fear. Like my main character, I wanted to be a Young Pioneer. My family shared a communal apartment. My father was a devoted Communist. And like my main character, I, too, had to make a choice. My choice was about whether to leave the country of my birth.

I set this story in the past, but the main issue in it transcends time and place. To this day, there are places in the world where innocent people face persecution and death for making a choice about what they believe to be right.

Â

âEugene Yelchin

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, California

Other books

Lucas by Kevin Brooks

Seduced by Darkness by Alex Lux

The Slayer by Theresa Meyers

A Pattern of Blood by Rosemary Rowe

Over the Line by Sierra Cartwright

Vintage Valentine (Elmheart Series) by Hardwick, Mindy

Legacy of Desire by Anderson, Marina

Some Girls Don't (Outback Heat Book 2) by Amy Andrews

Herb-Witch (Lord Alchemist Duology) by McCoy, Elizabeth

Demon Bound (Bound Series, Book One) by Eve Newton