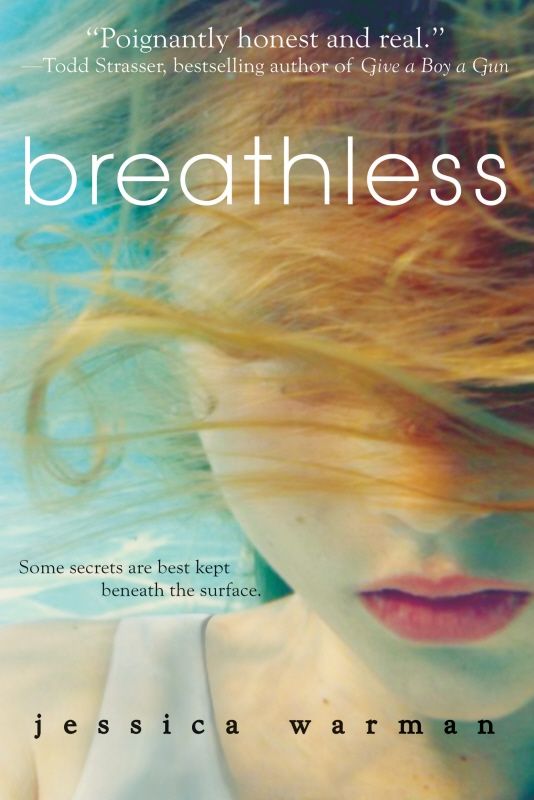

Breathless

breathless

jessica warman

Walker & Company New York

New York

All I wanted was to say honestly to people:

“Have a look at yourselves and see how bad and dreary

your lives are!” The important thing is that people should

realize that, for when they do, they will most certainly

create another and better life for themselves.

—Anton Chekhov

Table of Contents

A Conversation with Jessica Warman

There’s a man feeding the koi in our fishpond because my parents don’t want to do it themselves. Even though the pond has been there for years, the fish don’t have names. The man comes twice a week to feed the fish, once a week to prune the rose bushes and mow the lawn, and once a month to wash the outsides of all the windows. This afternoon, from our place on the roof, my brother and I watch with detached interest as he tosses a handful of food pellets into the fishpond. He glances over his shoulder to look at us warily. My brother and I wave, and he quickly looks away. I don’t know where my parents found him. I’m sure he has a name, but I don’t know that, either.

Life hasn’t always been like this. When I was a little girl, my family lived in a two-bedroom cottage in an area of rural Pennsylvania called the Bearlands. Even though I was so young, I remember almost everything about that life. I realize now that we were poor, but back then I never felt that way. My parents had paid their own way through college, and after we were born, my mom stayed home with me and my brother while my dad continued to work and go to medical school. They paid for everything themselves and we didn’t have much of anything. We didn’t have a TV or new clothes or lots of toys. We didn’t even have a telephone. It was all very

Swiss Family Robinson

.

For the first few years of my life, I shared the same room as my brother. My mother painted dinosaur murals on our bedroom walls. Once I was old enough to speak, he and I stayed up past bedtime every night to make up stories about them. They scared the hell out of me, but I had my brother to keep me safe.

For years we lived that way, the four of us tucked back in the woods, alone in that cottage together. My dad went hunting, and we ate whatever he caught. I loved venison; I still do. My mom had a big garden in our yard, where she grew zucchini and tomatoes and lettuce. She took us for walks every day. We watched baby birds hatching from their eggs; we picked blueberries and raspberries and cultured wild yeast to make our own bread. We watched tadpoles grow into frogs, their eggs collected in a plastic bowl filled with water that sat on our kitchen windowsill. We sat very still as children—but never still enough—while our mom sketched our faces with quick precision. We played hide-and-seek in the yard while she stood at her easel a few feet away, never letting us out of her sight for too long.

But our dad was almost never home, and one night, while my mom read us a story at bedtime, we heard a car pulling onto the gravel outside our house.

“It’s Daddy,” I said, rushing to get out of bed. I hadn’t seen him in days.

But my mother held out her arm in a panic. “It’s not your daddy. Come with me.

Now.

”

The three of us hid on the floor of my closet and listened. My mother kept her hands over our mouths. My brother and I wrapped our arms around her. I remember the way her body shook with fear. There were two men; we never saw them, but we heard their boots and their voices. Later on—much later—I learned they broke into four other houses besides ours in the Bearlands that night. Because we were in the closet, we were the only family they left unharmed.

Less than a month later, we moved to Hillsburg. I was four. My parents chose the town because it was safer than the city, safer than the country, and had lots of kids. Our house was the biggest in town, but like most of the other houses on our street, it was also a mess: peeling paint, cracked sidewalks, ugly wallpaper, and leaky ceilings.

Our parents called the house a money pit. My brother and I didn’t care. Our street was full of kids our ages. We had a nice big yard. My brother was so excited to go to a new, larger school, and I was thrilled by the possibility that, maybe someday, we could put a swimming pool in the backyard. Even then, at four years old, I could already swim like a sail slicing the wind on Narragansett Bay. My mom called me her water baby.

When I was five, a gallery in San Francisco started to sell her paintings, and after a while, she was making real money. Just after I turned six, my dad finished his MD and opened up a psychiatry practice. Pretty soon he had four offices in three counties, and we weren’t poor anymore. But by then, our dad worked so much that he’d started to vanish. My brother and I even gave him a nickname, which he

hated.

We called him “the Ghost.”

• • •

The less my dad was around, the more we seemed to

have.

My mom built a studio for herself at the bottom of our yard. My parents put in the swimming pool for me. We got a new minivan, new furniture, and a high stockade fence around our backyard that cut us off from our neighbors. Already, I know they had started to hate us. They were jealous. They watched us come and go, and the more we got, the less they smiled. It was right about that time when things started to go wrong with Will.

The summer before my sophomore year of high school feels hotter and muggier than those of any previous years. Lately I’m always sweaty and dirty. Instead of showering, I swim, which leaves me stinking of chlorine. When my brother is around, he doesn’t shower much either. He and I both sleep into the afternoon on most days, and we spend the rest of our time in a haze of swimming and slow conversation and whatever trouble we can think to get into.

I’ve always had a swimmer’s body, muscular but slim, and I keep my long blond hair—the same shade as the Ghost’s used to be, before he turned gray—knotted into a messy ponytail, when it’s not tucked underneath a swimming cap. This summer I’m usually barefoot, and always wearing the same ratty bikini covered in tiny, pink-lipped monkeys. The bathing suit hangs as though distracted from my body; it’s a little too big for me and threatens to fall away with the pull of a thread. The look drives my parents crazy, especially my father, who thinks I should carry myself with more class.

“I’m fifteen,” I remind him during one of his rare appearances in the afternoon.

He’s unblinking. “That’s right. You’re fifteen.” Then he likes to play the classic parent card. “I thought you were old enough to be treated like a

mature and responsible adult.

”

If he were around enough to know better, he would understand I’m already quicker than that. “Mature and responsible is one thing. But this is Hillsburg, Dad. Look around.” Our town’s most recent claim to fame occurred when the police busted up a meth lab in the basement of a home daycare service. “I’m not sure where you think all this class is supposed to come from.”

Before this summer started, I hadn’t seen my brother in five months, which is how long it’s been since his last stint in a psych unit. There have been so many episodes of his absence—three weeks here, six months there. All my childhood memories since we moved to Hillsburg fit together like a jigsaw puzzle, with pieces missing in the most conspicuous places: my birthday without my brother, age nine. Spring without him, age eleven. A whole childhood, not so whole.

For the longest time, the gaps in our relationship didn’t seem to matter. I missed him so much that it only made me love him more once he came home again. After all, we’d been friends since the day I was born. He taught me my first swear words. We still have it on videotape. One time, when we still lived in the Bearlands, my grandpa Effie came to visit and brought his camcorder. He left the tape with us; I’ve watched it at least a hundred times on our ancient VCR. I’m hobbling across the living room in my diaper, moving toward my young mother’s outstretched arms—I can’t be more than two years old—when I stop and fall suddenly onto my ass and say, “Oh, shit!”

Back then, my mother still had a sense of humor about some things. She dissolves into giggles, her face so young and pretty and strange, before the tape fades to black. Her eyes are kind and hopeful, excited to see her children growing up.

Since I was twelve years old and he was seventeen, anytime the weather is remotely good enough, and anytime he’s home, Will and I have snuck onto our roof to smoke and talk, wasting our afternoons taking delight in—as the Ghost would say—failing to meet our potential as Gifted Young People.

We are on the roof this afternoon, staring down at the koi man in the yard, at the glare of the sun reflecting off the surface of the pool. The heat on my back gives me goose bumps.

“There ain’t a thing to do in this town but get baked,” he says. He is always making wide statements like this, spreading his arms skyward in frustration as though the right plea might split open the town and free him.

“You got that right,” I agree. Will hasn’t been to a real school in years, so even though he’s actually far more brilliant than me, I always try not to sound like I’m being too smart around him. He’s sensitive about that kind of thing.

All afternoon we’ve been smoking this primo pot he got from someone he met at the hospital. Will tells me—and he should know—that crazy people always get the best drugs. Among the disgruntled teenage set, there seems to be an endless supply of whatever you want. All of Will’s friends are from other psych hospitals all over the state. When he’s home, he spends most of his time online in his bedroom.

Will asks, “Can you blame me for wanting to get high all the time?” And considering the circumstances—all that our parents and this town have put him through—I really can’t.

Will grows serious, sliding his sunglasses down the bridge of his nose—our mother’s nose—with his thumb and index finger, squinting against the backyard sunlight. “Hey. Katie.”

“What?”

“You see that cat down there?”

I move my head next to his. “Where?”

“Down there—don’t look!—down there next to the garage.”

“Yeah. So?”

“It

knows.

” My big brother straightens his spine and puts a hand on my shoulder. “Stay here.”

“Aw, Will, it doesn’t know anything.” A hint of a wheeze tickles my lungs. I ignore the feeling. “Gimme a cigarette.”

“No, dude. Pay attention to me.

Look

at it. It knows we’re high.” He reaches absently into his shirt pocket and extends a soft pack of Marlboros in my direction. He giggles.

Right there, in his laugh, I can sense his emotional axis shifting a little, off-kilter. It’s something I’ve come to call privately the kaleidoscope of crazy—shimmering and beautiful in certain lights, paisley and horrifying in others. Will is almost twenty-one and in certain lights looks more like twelve, in others closer to thirty. I know him as well as myself and not at all. All I can figure to do is hold on. He is my only brother.

Is he serious about the cat? I can’t tell. “It’s going to tell Mom and Dad,” he murmurs, gazing at it. “Katie, Katie, Katie. It’s going to tell on us.”

“Come on, quit it. I need a lighter, too.” Even now, after so many shaky recoveries that we hoped would last, it’s important to always have my guard half prepared around Will. He can go like nothing, out of nowhere.