Brilliant Blunders: From Darwin to Einstein - Colossal Mistakes by Great Scientists That Changed Our Understanding of Life and the Universe (8 page)

Authors: Mario Livio

There are, nevertheless, quite a few signs that Darwin had not been happy with blending heredity for quite a while. In a letter he wrote in 1857 to the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, his friend and champion in the public arena, he explained:

Approaching the subject [of evolution] from the side which attracts me most, viz inheritance, I have lately been inclined to speculate very crudely and indistinctly, that propagation by true fertilization, will turn out to be a sort of mixture and not true fusion, of two distinct individuals, or rather innumerable individuals, as each parent has its parents and ancestors. I can understand on no other view the way in which crossed forms go back to so large an extent to ancestral forms. But all this, of course, is infinitely crude.

Crude or not, this observation was extremely insightful. Darwin recognized here that the combination of paternal and maternal heredity material was more like the shuffling together of two packs of cards rather than like the mixing of paints.

While Darwin’s ideas in this letter can definitely be considered impressive forerunners of Mendelian genetics, Darwin was

eventually driven by his frustration with blending heredity to develop a completely wrong theory known as

pangenesis.

In Darwin’s pangenesis, the entire body was supposed to issue instructions to the reproductive cells. “I assume,”

he wrote in his book

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication,

that cells, before their conversion into completely passive or “formed material” throw off minute granules or atoms, which circulate freely through the system, and when supplied with proper nutriment multiply by self-division, subsequently becoming developed into cells like those from which they were derived. . . . Hence, speaking strictly, it is not the reproductive elements . . . which generate new organisms, but the cells themselves throughout the body.

To Darwin, the great advantage that pangenesis offered over blending was that if some adaptive change were to occur during the lifetime of an organism, then the granules (or “gemmules,” as he called them) could take note of the change, lodge in the reproductive organs, and ensure that the change would be transmitted to the next generation. Unfortunately, pangenesis was taking heredity precisely in the opposite direction from which modern genetics was about to direct it—it is the fertilized egg that instructs the development of the entire body, not the other way around. Confused, Darwin clung to this misguided theory with similar conviction to that which he exhibited when he had previously held on to his correct theory of natural selection. In spite of vehement attacks by the scientific community, Darwin wrote to his great supporter Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1868: “I fully believe that each cell does actually throw off an atom or gemmule of its contents; but whether or not, this hypothesis serves as a useful connecting link for various grand classes of physiological facts, which at present stand absolutely isolated.” He also added with confidence that even “if pangenesis is now stillborn, it will, thank God, at some future time reappear, begotten by some

other father, and christened by some other name.” This was a perfect example of a brilliant idea—particulate inheritance—that failed miserably because it had been incorporated into the wrong mechanism for its implementation: pangenesis.

Nowhere did Darwin articulate more clearly his atomistic, essentially Mendelian, ideas of heredity than in an exchange with Wallace in 1866.

First, in a letter written on January 22, he noted, “I know of a good many varieties, which must be so called, that will not blend or intermix, but produce offspring quite like either parent.” Failing to see Darwin’s point,

Wallace replied on February 4, “If you ‘know varieties that will not blend or intermix, but produce offspring quite like either parent,’ is not that the very physiological test of a species which is wanting for the

complete proof

of the ‘origin of species.’ ”

Realizing the misunderstanding,

Darwin was quick to correct Wallace in his next letter:

I do not think you understand what I mean by the nonblending of certain varieties. It does not refer to fertility. An instance will explain. I crossed the Painted Lady and Purple sweet peas, which are very differently coloured varieties, and got, even out of the same pod, both varieties perfect, but none intermediate. Something of this kind, I should think, must occur at first with your butterflies and the three forms of Lythrum; though these cases are in appearance so wonderful, I do not know that they are really more so than every female in the world producing distinct male and female offspring.

This letter is remarkable in two ways. First, Darwin describes here the results of experiments similar to those conducted by Mendel—actually, the very experiments that had led Mendel to the formulation of Mendelian heredity. Darwin came pretty close to discovering the Mendelian 3:1 ratio by himself. After he crossed the common snapdragon (having bilateral symmetry) with the peloric (star-shaped)

form, the first generation of offspring were all of the common type, and the second had eighty-eight common to thirty-seven peloric (a ratio of 2.4:1). Second,

Darwin points out the obvious fact that the simple observation that all offspring are either male or female, rather than some intermediate hermaphrodite, in itself argues against “paint-pot” blending! So the evidence of the proper form of heredity was right there in front of Darwin’s eyes. As he had already remarked in

The Origin:

“The slight degree of variability in hybrids from the first cross or in the first generation, in contrast with their extreme variability in the succeeding generations, is a curious fact and deserves attention.” Note also that the entire Darwin-Wallace correspondence above took place

before

the publication of Jenkin’s review. All the same, even though Darwin came tantalizingly close to Mendel’s discovery, he did not grasp its all-encompassing generality, and he failed to recognize its vital importance for natural selection.

To fully understand Darwin’s attitude toward particulate heredity, there are a few other nagging questions that need to be resolved.

Gregor Mendel read the seminal paper describing his experiments and his theory of genetics—“Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden” (“Experiments in Plant Hybridization”)—to the Brünn (Moravia) Natural History Society in 1865. Is it possible that Darwin read that paper at some point? Were his letters to Wallace in 1866 inspired (to some extent at least) by Mendel’s work rather than representing his own insights? If he had read Mendel’s paper, why didn’t he see that Mendel’s results provided the definitive answer to Jenkin’s criticism?

Intriguingly,

no fewer than three books published between 1982 and 2000 alleged that copies of Mendel’s paper had been found in Darwin’s library,

and a fourth book (published in 2000) even claimed that Darwin had supplied Mendel’s name for inclusion in the

Encyclopaedia Britannica,

under an entry of “hybridism.” Obviously, if this last claim were shown to be true, it would mean that Darwin was fully aware of Mendel’s work.

Andrew Sclater of the Darwin Correspondence Project at Cambridge University responded definitively to all of these questions in 2003. As it turns out, Mendel’s name (as an author) does not appear

even once in the entire list of books and articles owned by Darwin. This is not surprising, given that Mendel’s original paper appeared in the somewhat obscure proceedings of the Brünn Natural History Society, to which Darwin had never subscribed. Furthermore, Mendel’s work languished almost unread for thirty-four years, until its rediscovery in 1900, when the botanists Carl Correns of Germany, Hugo de Vries of Holland, and Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg of Austria published supporting evidence independently. Nevertheless, two of the books that were in Darwin’s possession did refer to Mendel’s work. In Darwin’s book

The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom,

he even cited one of those books: Hermann Hoffmann’s

Untersuchungen zur Bestimmung des Werthes von Species und Varietät

(

Examinations to Determine the Value of Species and Variety

), published in 1869. However, Darwin never cited Mendel’s work, nor did he annotate any mention of Mendel in Hoffmann’s book. Again, this is hardly surprising, since Hoffmann himself did not comprehend the significance of Mendel’s work, and he summarized Mendel’s conclusions by the rather low-key statement “Hybrids possess the tendency in the succeeding generations to revert to the parent species.” Mendel’s pea experiments were mentioned in another book owned by Darwin:

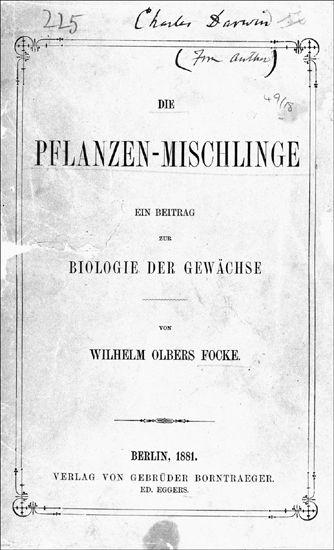

Die Pflanzen-Mischlinge

(

The Plant Hybrids

), by Wilhelm Olbers Focke.

Figure 7

shows the title page, on which Darwin wrote his name. As I’ve seen with my own eyes, this book had an even less distinguished fate: The precise pages describing Mendel’s work remained uncut in Darwin’s copy of the book! (In old bookbinding, pages were connected at the outer edges and had to be cut open.)

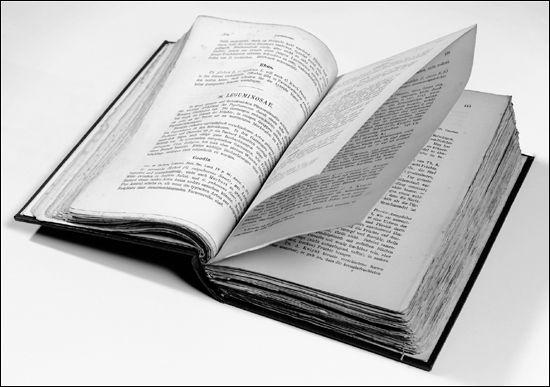

Figure 8

shows a picture of Darwin’s copy, made at my request, displaying the uncut pages. However, had Darwin read those pages, he would not have been much enlightened, since Focke failed to grasp Mendel’s principles.

One question still remains: Did Darwin indeed suggest Mendel’s name to the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

? Sclater left no doubt as to the answer: No, he did not. Rather, when asked by the naturalist George Romanes to read a draft on hybridism for the

Britannica

and to provide references, Darwin sent him his copy of Focke’s

book (with the uncut pages), suggesting to Romanes that the book could “aid you much better than I can!”

Figure 7

Figure 8

In contrast to Darwin’s total lack of familiarity with Mendel’s work, Darwin’s theories did have a clear influence on Mendel’s ideas, although not in 1854–55, when Mendel started his experiments with peas. Mendel possessed the second German edition of

The Origin

, which was published in 1863. In his copy, he marked certain passages by lines in the margin and others by underlining parts of the text. Mendel’s markings show great interest in topics such as the sudden appearance of new varieties, artificial and natural selection, and differences between species. There is little doubt that reading

The Origin

had significantly affected Mendel’s own writing by 1866, since Mendel’s paper reflects in many places various aspects of Darwin’s concepts. For instance, in discussing the origin of heritable variation, Mendel wrote:

If the change in the conditions of vegetation were the only cause for variability, one would expect that those cultivated plants which have been grown for centuries under almost constant conditions would revert again to stability. As is well known this is not the case, for it is precisely among such plants that not only the most varied, but also the most variable forms are found.

We can compare this language to that used in one of Darwin’s paragraphs in

The Origin:

“No case is on record of a variable organism ceasing to vary under cultivation. Our oldest cultivated plants, such as wheat, still yield new varieties: our oldest domesticated animals are still capable of rapid improvement or modification.” Most importantly, however, it seems that Mendel may have realized that

his theory of heredity could solve Darwin’s main problem: an adequate supply of heritable variations for evolution to influence. This was precisely where blending inheritance was failing, as pointed out by Jenkin. Mendel wrote:

If it be accepted that the development of hybrids takes place in accordance with the Law established for

Pisum

[peas], each experiment must be undertaken with a great many individuals . . . In

Pisum

it has been proved by experiment that hybrids produce ovules and pollen-grains of differing constitutions, and that this is the reason for the variability of their offspring.