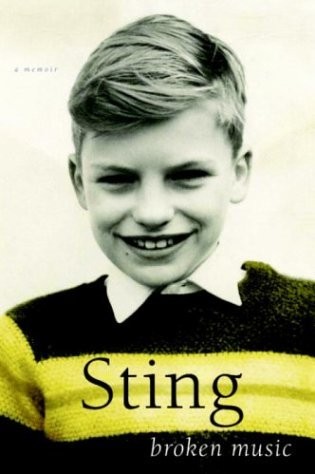

Broken Music: A Memoir

Read Broken Music: A Memoir Online

Authors: Sting

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Biography, #Personal Memoirs, #England, #Rock musicians, #Music, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Rock, #Genres & Styles, #Singers, #Musicians

Having been a songwriter most of my life, condensing my ideas and emotions into short rhyming couplets and setting them to music, I had never really considered writing a book. But upon arriving at the reflective age of fifty, I found myself drawn, for the first time, to write long passages that were as stimulating and intriguing to me as any songwriting I had ever done.

And so

Broken Music

began to take shape. It is a book about the early part of my life, from childhood through adolescence, right up to the eve of my success with the Police. It is a story very few people know.

I had no interest in writing a traditional autobiographical recitation of everything that’s ever happened to me. Instead I was compelled to explore specific moments, certain people and relationships, and particular events which still resonate powerfully for me as I try to understand the child I was, and the man I became.

It is a winter’s night in Rio de Janeiro, 1987. It is raining and the boulevard in front of the Copacabana Hotel is deserted. The road is slick and shining in the light of the street-lamps. My wife, Trudie, and I are sheltering beneath an umbrella, while high above our heads two seagulls wheel recklessly in the wind; and the sea is a roaring threat in the darkness. A small car pulls up to the curbside. There are two figures silhouetted in the front seat, and an opened rear door beckons us inside.

A series of discreet phone calls have secured us an invitation to a religious ceremony in a church somewhere in the jungles that surround the great city. Our drivers, a man and a woman, tell us only that the church is located about an hour and a half from the Copacabana, that we will be looked after, and we shouldn’t worry. The church, while nominally Christian, is the home of a syncretic religious group that uses as its core sacrament an ancient medicine derived from plant materials known as ayahuasca, and it is said to induce extraordinary and profound visions.

It is now raining heavily as we head south, and a massive

lightning storm strobes above the mountains that surround the city, followed by the deep rolling percussion of distant thunder. Trudie and I sink back into our seats, excited and a little apprehensive, wondering what the night holds in store. The driver is intent upon the road in front of us. I am seated directly behind him; he has a large head atop wide athletic shoulders and, when he turns toward us, an intelligent and aquiline face, framed in wire-rimmed spectacles and untidy brown hair. His companion, an attractive young woman with long dark curls and a wide Brazilian smile, turns to us reassuringly and asks if we are comfortable. We both begin to nod mechanically, clearly nervous but not wanting to admit it to each other or to our hosts.

We leave the wide boulevards of the city, and as the luxury hotels of the Copacabana give way to the chaos of the hillside favelas that glitter like Christmas trees in the darkness, the streetlights grow scarcer and scarcer. Soon the road becomes a dirt track and the car slows down to a walking pace as our driver negotiates axle-breaking potholes and sullen, immovable dogs. The rain has stopped, but the jungle drips in the heavy air, the noise of the cicadas all but drowning out the cheap cantina music on the little car radio. Eventually we pull into a clearing where many cars are parked chaotically around a large building with a tiled roof. The structure, while simple and utilitarian, is not one I would normally associate with the word “church” (it has no doors or windows), and the event has more the air of a town meeting than a religious gathering.

Men and women of all ages, including teenagers and small children, and the ubiquitous dogs mingle in the car park and inside the church, which is lit by naked electric bulbs strung

from the ceiling. Everyone is wearing either a blue or green shirt, on which several have sewn gold stars. These are clearly uniforms. Our two drivers take off their coats to reveal that they too are wearing blue shirts. Suddenly I feel vulnerable and conspicuous. We didn’t expect uniforms. Uniforms make me feel uneasy, and for me are somehow linked to ideas of control and conformity, to something belying freedom, something cultish. A lurid newspaper headline flashes into my head: SINGER AND WIFE ABDUCTED IN JUNGLE BY RELIGIOUS CULT. Would I have felt more comfortable if everyone had looked like a stoner freak? Probably not, but the uniforms definitely throw me.

As we step into the light of the large hall, we are welcomed with warm, open smiles and introduced by our two drivers to what appears to be a cross section of Brazilian society. Many of them speak English, and after some brief courtesies I ask a few of them what they do for a living, explaining that my wife is an actor and I’m a singer. “Yes, we know,” says one woman. “You are very famous, but my husband and I are schoolteachers.”

They all seem like everyday working people, and many are professionals as well: doctors, lawyers, firemen, an accountant and his jolly wife, social workers, civil servants, computer programmers, teachers; not one stoner freak among them. I don’t really know what I was expecting, but this large and hospitable group reassures me.

“Is this your first time to drink the vegetal?” asks a doctor.

We haven’t heard the fabled medicine referred to in that way before, but assume that they mean ayahuasca, which I suppose is its indigenous Indian name.

“Yes, it’s our first time.”

There are a few knowing smiles. “You’ll be fine,” says one of the schoolteachers.

We attempt to smile back, again suppressing whatever apprehensions we may be having.

There are now about two hundred people in the room, which is filled with lounge chairs of woven plastic over metal frames arranged in a circle around a central table. Above the table is a wooden arch painted blue with

LUZ, PAZ, AMOR

written in bright yellow letters. “Light, peace, love,” I manage to decipher in my rudimentary Portuguese. Our two drivers, who seem to be our guardians for the evening, reappear and usher us to our seats near the front. They assure us they will help out should we get into difficulties.

“Difficulties?” I query, unable to mask my concern.

There is a slight uneasiness in the man’s voice as he replies, “You may experience some physical as well as emotional discomfort. But please try and relax, and if you have any questions, I will try and answer them for you.”

Around the table are five or six empty dining chairs. Silence filters through the room as half a dozen men enter the church from a side door and make their way to the central table. There is a distinct gravitas in their stately procession, and from the bearing of their shoulders I surmise they are figures of some authority. Perhaps the drama of the occasion is already distorting my perception, but they all seem to have the drawn, ascetic look of monks or wise elders. These are the

mestres

who will preside over the ceremony.

The central chair is occupied, we are told, by a visiting

mestre

from the northern city of Manaus. It is he who will lead the ritual. He is a man in early middle age with deep-set,

thoughtful eyes, which peer out from a faintly ironic but not unkind face, as if he is viewing the world outside from a long dark tunnel. He seems to me like a man with an amusing secret to impart, a story to tell, or a piece of arcane wisdom. I am intrigued. I also feel a little happier in noticing how easily his face breaks into an engaging smile when he greets someone he knows. His obvious warmth is comforting.

In the middle of the table is a large glass container full of brown, sludgy liquid. I assume that this is the legendary sacrament I have read so much about, ayahuasca.

The

mestre

indicates that we should join the orderly queue that is forming in the aisle and snaking to the back of the room. We seem to be the only novices present and are guided politely to the front of the queue, then handed white plastic coffee cups. The

mestre

fills these reverently from the glass container, which has a metal spigot at its base.

Despite the reverence of the ceremony, the sacramental liquid looks like something you would drain from the sump outlet of an old engine; a furtive twitch of the nostrils confirms my apprehension that it smells as bad as it looks. “Are we really going to swallow this muck?” I think to myself. “We must be crazy.”

Still apprehensive about the difficulties we may encounter, I try to forget that we could be carousing right now in the comfort of the hotel bar on the Copacabana, quaffing sweet caipirinhas and swaying to the gentle rhythm of the samba. But it is too late to turn back now. My wife and I look at each other like tragic lovers on a cliff top. The room begins to reverberate with a chanted prayer in Portuguese. Unable to join in, I mutter, “God help us,” under my breath, only half ironically. Then everyone drinks.

“Well, bottoms up,” says Trudie, with her usual gallows humor. “Here goes.”

I manage to swallow the entire brew in one shuddering gulp, and yes, it tastes foul, and I’m relieved that most people in the room seem to think so too. I know this from the grimaces and the hurried sucking of lemons and mints that have been distributed to suppress the noxious taste it leaves in the mouth. I manfully decline a proffered mint for no reason other than obstinate pride in taking it straight, while the ever practical Trudie wisely accepts the kindness. One of the attendant

mestres

places a record onto an old-fashioned turntable; it is simple Brazilian folk music, light and pleasantly banal. The congregation begin to make themselves comfortable in their seats, and Trudie and I try to follow suit, dozing to the pleasant cadences of guitars strummed in major keys and the easy rhythm of a tambura. We sit down and wait, neither of us having any clear idea of what will happen next. I too begin to drift off, keeping a discreet eye on the room, while breathing softly and deliberately, trying to calm my nerves.

I wonder if William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg suffered the same apprehension when they had this experience. The novelist and the beat poet had gone in search of ayahuasca in the late fifties, the medicine having an almost legendary status as the sine qua non of the ethnogenic realm. Known also as yaje, the vine of the soul, and dead man’s root, among many other names, its origins and usage are perhaps thousands of years old and inextricably linked with the development of the ancient religious philosophies and rituals of the Amazon basin. From my reading I had gleaned that ayahuasca is brewed from two indigenous plants, a liana known as

Banisteriopsis caapi

and a shrub of the coffee genus,

Psychotria viridis

. The active molecule in the medicine is almost identical to the neurotransmitter serotonin, and its chemical interaction with the human brain is just as complex and mysterious. I had been reassured by my research that the practice is legally protected by the Brazilian constitution and that its ingestion is said to be non-addictive and its effects profound.

I am in the country at this time because I’m about to begin a Brazilian tour, and in a few days I will be playing the biggest concert of my life. Two hundred thousand people will be packed into the Maracana Stadium in Rio. The event will mark the pinnacle of my solo career in South America, but it will also be something of a wake. My father has died only a few days before, and his death comes only months after my mother has passed away. For complex reasons I have attended neither funeral, nor will I seek any consolation from the church. But just as the recently bereaved can be drawn to the solace of religion, psychoanalysis, self-reflection, and even séances, despite my agnosticism, I too am in need of some kind of reassuring experience or ritual that will help me to accept that perhaps there is something beyond the tragedy of death, some greater meaning than I can conjure for myself.