Bronx Justice (14 page)

But where Eleanor Cerami had been easy to lead, Joanne Kenarden proved more than a match for him.

KENARDEN: No, sir. There was light coming from a huge window.

Jaywalker moved on to the information Miss Kenarden had given the police. He drew from her that she'd described a man twenty-five to thirty years old, weighing approximately 175 pounds. She'd also characterized his eyes as “hooded,” with a large area of the eyelid visible even when his eyes were open, giving him a “sleepy” appearance. And she'd said his breath had an odor of alcohol, specifically wine.

Darren was bright-eyed; there was nothing sleepy-looking about him. And though he drank in moderation on social occasions, his taste ran to Scotch.

Jaywalker knew from the police reports that Miss Kenarden had reported that the man was circumcised. Darren had told Jaywalker that he wasn't. Knowing that the difference in appearance is slight in an erect penis but significant in a flaccid one, Jaywalker wanted to get Miss Kenarden to say that at some point she'd seen her attacker in a nonerect state.

JAYWALKER: After the first part of your conversation with the man, there came a time when he told you he wanted you to go down on him, and he unzipped his pants. Is that correct?

KENARDEN: Yes.

JAYWALKER: Do you recall if he was wearing a belt?

Jaywalker had learned then when dealing with a hostile witness, it sometimes paid to camouflage the important questions. It wasn't so different from the way Dick Arledge or Gene Sandusky had sprinkled in control questions about Darren's age or address. By keeping the witness slightly off guard, he hoped to prevent her from knowing in what direction he was heading.

KENARDEN: No belt.

JAYWALKER: And did he take his penis out?

KENARDEN: He didn't have to. He was exposed.

JAYWALKER: Was it erect at that point?

KENARDEN: No, sir.

JAYWALKER: Are you certain of that?

KENARDEN: Yes, I am.

JAYWALKER: Were you able to determine if the man was circumcised or not?

KENARDEN: He was.

JAYWALKER: He was circumcised. You're certain of that, also?

KENARDEN: Yes, sir.

On direct examination, Miss Kenarden had testified that during intercourse, the man had put the knife down at one point. Jaywalker saw another chance to emphasize his right-handedness.

JAYWALKER: Was he facing you at the time he did this?

KENARDEN: Yes.

JAYWALKER: Where did he put the knife?

KENARDEN: On the stairs, about two steps down.

As she answered, she pointed. And pointed to her left.

JAYWALKER: You're indicating to your left.

KENARDEN: Yes, sir.

JAYWALKER: So the man put it down on his right?

KENARDEN: That's where the stairs were, to his right.

JAYWALKER: So the knife was in his right hand as he put it down?

KENARDEN: Yes, sir. It was in his right hand.

Jaywalker brought out that, like Eleanor Cerami, Joanne Kenarden had noticed no scars or deformities on the man. As had Mrs. Cerami, she recalled dirty gray sneakers, but she couldn't say if they were low-cut or high-cut. And despite all her conversation with the man, she'd never once heard him stutter.

It seemed as good a point as any to quit on.

Pope, on redirect examination, sought to reinforce the certainty of his witness's identification of the defendant as her attacker.

POPE: Is there any doubt in your mind, Miss Kenarden, that this man, Darren Kingston, is the man who raped you on August sixteenth, nineteen-seventy-nine?

KENARDEN: No, sir, there is no doubt.

But Jaywalker managed to get the last word in, on recross.

JAYWALKER: Is there any doubt that he held the knife in his right hand?

KENARDEN: No, sir, there is no doubt.

JAYWALKER: Any doubt that he was circumcised?

KENARDEN: No, sir, no doubt.

Jaywalker took his seat. Joanne Kenarden stepped down from the witness stand and strode out of the courtroom, as defiant as ever. Justice Davidoff recessed the trial until the following morning.

Â

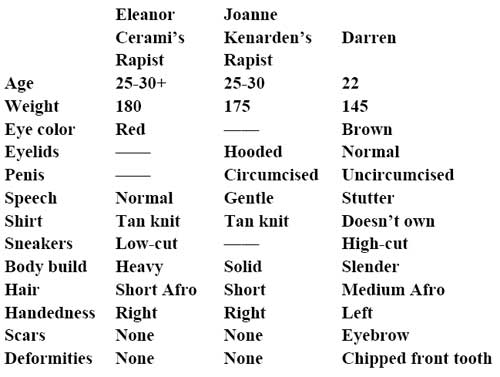

Late that night, Jaywalker found himself unable to fall asleep. Not that there was anything unusual about that. They were finished with the two victims' testimony. Though both had pointed Darren out as their rapist with unflinching certainty, Jaywalker felt he'd nonetheless scored some points. He'd managed to lay the groundwork for demonstrating a number of discrepancies between the man the victims had described and the one who was on trial.

While his wife and daughter slept, Jaywalker sat at the kitchen table, scribbling notes.

While some of the discrepancies were arguably minor, some were truly significantâthe stutter, for example, and the circumcision, and the left-or right-handedness. Perhaps even more tellingly, wherever the victims were off the mark in describing the defendant, their versions barely departed from each other. In other words, they were describing the same man; it just didn't happen to be Darren.

But in order to drive this point home, Jaywalker knew, he would have to put Darren on the stand, as well as other members of his family. He would have to prove, for example, that Darren was left-handed, that he hadn't lost weight since last August, and that he'd never owned the shirt or sneakers the witnesses had described. Because judges tend to disapprove of people dropping their pants on the witness stand, Jaywalker would have to find a doctor to examine Darren and testify that he wasn't circumcised. On top of those things, he would need to round up witnesses from the post office to show, if they could, that Darren had been at work at the time Eleanor Cerami

claimed she'd seen him again in her lobby, a secondâor perhaps a thirdâtime.

And if he did all those things and more, was that going to be enough? Would logic prevail? Or were the jurors simply going to throw all that to the wind and remember only how absolutely certain the two victims had been that Darren Kingston was the man who'd raped them?

It would be a long time before Jaywalker would make it to bed, and an even longer time before anything remotely resembling sleep would come his way.

THE CYCLONE

J

acob Pope's first witness Tuesday morning was a gynecologist from Jacobi Hospital named David Blume. Dr. Blume had examined Joanne Kenarden; a Dr. Genovese had examined Eleanor Cerami, but he was currently out of the country. So Dr. Blume was called to describe the findings from both examinationsâMiss Kenarden's from his own recollection and Mrs. Cerami's from Dr. Genovese's notes.

Eleanor Cerami had been seen at 3:50 p.m. on August 16th. She'd presented as agitated and nervous. There'd been no sign of external injury, such as bruises or lacerations. A pelvic examination had revealed no obvious evidence of internal injury. A vaginal smear had been taken, and upon microscopic examination it had revealed the presence of one or two sperm.

Today, of course, those one or two sperm might have made all the difference in the world. With DNA testing, it's entirely possible that a technician could have enhanced the sample and typed it, and then provided the jury with

a genetic profile of the sperm donor, either establishing beyond astronomical odds that it was indeed Darren Kingston or excluding him with an equal degree of scientific certainty. But this was 1980, and the technique was still in its infancy. Genetic typing had only begun to be seriously studied, and it would be years before it would begin to make the journey from the laboratory to the courtroom.

Joanne Kenarden had been seen at 1:13 a.m. on August 17th. She'd complained of pain to her lower back, and Dr. Blume had found some tenderness in the area. Microscopic examination of a vaginal smear had revealed no sperm.

Jaywalker's cross-examination of Dr. Blume was brief. He established that during intercourse a fertile young male would normally discharge as many as sixty to a hundred million sperm, some of those even prior to ejaculation. But there was little more Jaywalker could do. The fact that the rapist hadn't ejaculated in Mrs. Ceramiâor “shot,” as he might have phrased itâmade the discovery of only one or two sperm in a representative smear seem reasonable. And Miss Kenarden's testimony had left little doubt that ejaculation had taken place in her mouth, rather than in her vagina. That fact, coupled with her delay in going to the hospital, rendered meaningless the absence of sperm in her swab.

Â

Pope next called Dr. Paul Jarakanak, a surgical resident at Jacobi Hospital. Joanne Kenarden had been referred to him by Dr. Blume, and he'd examined her later that same morning, August 17th. Dr. Jarakanak had found tenderness in the lower vertebrae, and had ordered X-rays, which had failed to disclose any fracture or dislocation. Still, accord

ing to Dr. Jarakanak, Miss Kenarden's tenderness could have been caused by trauma or physical injury.

All of these findingsâwith the exception of the one or two sperm found in Mrs. Cerami's swabâadded up to almost nothing, in medical terms. But Jaywalker understood the prosecution's interest in nevertheless pursuing them. Pope was concerned about the corroboration requirement. It would be his position that in Mrs. Cerami's case, corroboration could be found in the sperm, which, according to both Mrs. Cerami and her husband, could only have come from her attacker. In Miss Kenarden's case, with the absence of sperm, Pope would argue that the lower back tenderness supplied corroboration.

But to Jaywalker, tenderness was a complaint, not a finding. With no fracture, dislocation, bruising or even redness in the lower back area, the doctors had been essentially taking Miss Kenarden's word that she was in pain. But her word wasn't corroboration at all. Quite the contrary: under the law, it was her word that

required

corroboration.

But that was a legal distinction that would have to be argued later on, before the judge. For now, on cross-examination, Jaywalker had to settle for establishing that neither of the doctors who'd examined Joanne Kenarden had been able to

see

evidence of painâthe bruising and swelling she'd claimed to sufferâeither by looking at her back or studying her X-rays. And even if the area was in fact tender, that tenderness could have been the result of infection, arthritis, muscle strain, dysmenorrhea or just about anything else, for that matter.

Â

As his final witness, Pope called Detective Robert Rendell. Jaywalker winced as Rendell entered the court

room, knowing that the jurors couldn't help but be influenced by his appearance. Tall, good-looking and beginning to gray around the temples, Rendell would be a relaxed and well-spoken witness, Jaywalker knew, one who would impress the jurors as being honest and fair. Looking back on the case twenty-five years after the fact, Jaywalker would have no reason to rethink that assessment.

In response to Pope's background questions, Rendell stated that he'd been with the NYPD for eleven years, five of those as a detective. He gave his current assignment as the Bronx Sex Crime Squad, but indicated that back in August of 1979 he'd been working out of the 8th District Burglary and Larceny Squad. Even then, he'd specialized in rape cases, some of which began as break-ins, and therefore burglaries. Jaywalker couldn't help but wonder if it had been Darren Kingston's arrest that had “made” Rendell and earned him the new assignment.

On August 16th, Rendell had been working an evening tour of duty, from 5:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. Around 11:00 or 11:15, an individual named Joanne Kenarden had come into the squad room. Today, chances are she would be assigned a female detective; in 1979, that sort of sensitivity was unheard of. In any event, it was Rendell who had interviewed her, helped her file a complaint report and driven her in his radio car to Jacobi Hospital. After that, he'd gone to the scene of the crime Miss Kenarden had described.

POPE: What did you do there?

RENDELL: I surveyed the scene. I spoke with people in the area. I removed some lightbulbs, which I

dusted for latent fingerprints. But there were none of any value.

POPE: When you say none of any value, you mean there were no prints on the bulbs?

RENDELL: No. There were some partial prints on the bulbs, but none of any value.

Rendell soon inherited another investigation, that of the Eleanor Cerami rape. Although he himself hadn't conducted the initial survey of the crime scene in that case, Justice Davidoff permitted Pope to ask Rendell what he knew about it.

POPE: With respect to the complainant Eleanor Cerami, was any physical inspection done?

RENDELL: Detective Talbot conducted a survey of the scene and also removed some lightbulbs, which he had tested for fingerprints but which were also negative. No latent prints of any value.

Pope's next question must have truly mystified the jurors. They, of course, knew nothing about the gathering of three of the original five victims to meet with the sketch artist. They knew nothing of the intensity of the women's emotional reactions upon first coming across the mug shot of Darren Kingston. They would never hear about the photo array Rendell had subsequently created, or the fact that Mrs. Cerami and Miss Kenarden, as well as Tania Maldonado, had succeeded in picking out Darren's photo

from seventeen others. Because Pope was prohibited by the law from bringing out the photo identifications, and because Jaywalker had made a tactical decision to steer clear of the dramatic events that had unfolded that day, the jury would be forever kept in the dark about what it was that had caused the investigation to focus on Darren.

POPE: And did there come a time, Detective Rendell, when, as a result of your investigation, you began to look for one Darren Kingston?

RENDELL: Yes.

POPE: And approximately when was that?

RENDELL: August twenty-fourth.

Rendell testified that it had taken him nearly three weeks to locate and arrest Darren. If he deserved high marks for being honest and fair, Rendell was revealing himself here as being something short of an accomplished investigator. The address on the back of Darren's mug shot was that of his parents, with whom he'd been living a year and a half earlier. Since that time, he and Charlene had found an apartment of their own. A check with the phone company would have netted that address in five minutes' time, as would a simple question to his parents.

According to Rendell, the defendant had spoken softly and clearly at the time of his arrest. But later on, when permitted to make a phone call, he'd begun to stutter noticeably. At the precinct, there were times when he stuttered and times when he didn't.

Lastly, Pope tried to establish through Rendell that the stairwell where Joanne Kenarden was assaulted was well-illuminated by a large window to the outside. But Rendell replied that he'd never visited that particular location during daylight hours. If Pope ended on a note of minor frustration, that fact was more than offset by Rendell's use of the opportunity to impress the jurors with his candor.

As the first business of his cross-examination, Jaywalker wanted to dispel any suggestion that Darren had been hiding out during the three weeks when Rendell had been looking for him. He brought out that the detective had eventually gone to the home of Darren's parents, who'd readily provided him with their son's address. Then, by eliciting from Rendell that both Darren and his parents had telephones in their homes, he laid a foundation for proving later on that, following Rendell's visit, the Kingstons had promptly phoned Darren, whoâeven when informed that the police were looking for himâhadn't fled. Next Jaywalker established that Rendell had never bothered to obtain a search warrant for Darren's apartment in order to find out if Darren owned a tight-fitting, short-sleeved, tan V-necked shirt, a pair of dirty gray low-cut sneakers or a knife that matched the one described by the victims.

From there, Jaywalker moved on to Rendell's version of the phone call made by Eleanor Cerami after she thought she'd seen Darren in her building again.

JAYWALKER: Now there came a time, did there not, when Mrs. Cerami called your office and reported seeing her attacker again?

RENDELL: That's correct.

JAYWALKER: Did you receive Mrs. Cerami's call when she phoned?

RENDELL: No, I did not receive it.

JAYWALKER: How were you informed of it?

RENDELL: A message was left for me that she had called.

JAYWALKER: How soon did you get the message?

RENDELL: The same day.

JAYWALKER: Did this happen once? Or twice?

RENDELL: Just once.

JAYWALKER: Can you fix a date for us?

RENDELL: September seventeenth, the Monday after Kingston's arrest.

The date matched. Jaywalker was halfway there. Eleanor Cerami had said it was a Monday, about 9:30 in the morning. Now Rendell had supplied the date. If Jaywalker was right, post-office employees could place Darren at his job, literally miles from Castle Hill. And if Eleanor Cerami could be wrong, despite her absolute certainty, that her attacker was back, so, too, could she be wrong about her identification of Darren. And if she

was

wrong, didn't that mean Joanne Kenarden was, too?

Trying hard to conceal his excitement, Jaywalker cemented the date.

JAYWALKER: There's no question in your mind that it was on Monday, September seventeenth, that you received the message?

RENDELL: I'm almost positive. I contacted the district attorney immediately.

JAYWALKER: You contacted Mr. Pope. And you know that Mr. Pope spoke to me about that.

RENDELL: That's correct.

JAYWALKER: And all of that was on Monday, September seventeenth?

RENDELL: That's correct.

JAYWALKER: Thank you, sir.

Jaywalker sat down. He had what he wanted from Rendell. Pope stood and announced that the detective had been his final witness, and that the People's case was concluded. After a brief conference at the bench, Justice Davidoff sent the jury home until the following morning.

Â

At the end of the prosecution's case, the defense gets a chance to ask the judge to have the case dismissed. The motion takes on different names in different jurisdictions, but the theory is the same: that even if every word of the

prosecution's case were to be accepted as true by the jury, those words still don't add up to be legally sufficient to support a conviction on the charges.

As Jaywalker rose to make the motion and argue in support of it, he had no illusions. He knew full well that Justice Davidoff would rule against him. Being a good judge doesn't necessarily mean you've got the biggest balls in town. Max Davidoff had come up through the system, running errands, paying clubhouse dues, and learning the art of politics long before he'd become a district attorney and then a judge. Nearing mandatory retirement age now in the final job he would likely ever have, the very last thing in the world he wanted was to wake up in the morning to a headline screaming

Â

SOFT-ON-CRIME JUDGE

FREES RAPIST OF FIVE!

Â

Still, Jaywalker knew that with respect to the corroboration element, the case was a close one, and if there was a conviction, some appellate court was going to have to wrestle with it.

The ancient and archaic rule requiring corroboration in sex cases grew out of a beliefâchampioned in legislatures that were ninety-nine percent maleâthat accusations of rape were too easily made and were often contrived out of some ulterior motive on the part of the accuser. In order to protect innocent gentlemen from this sort of abuse, the lawmakers enacted a rule requiring that a complainant's testimony be supported by independent evidence with respect to each and every element of the crime.

Elements

are those things the prosecution is required to prove. In a

forcible rape prosecution, that meant there had to be additional proof that the defendant was the perpetrator, that his penis actually penetrated the complainant's vagina, and that he accomplished his goal through the use of force.