Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (18 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

I doubt his sincerity looking back, but his words started the wheels turning in my head. Boston medicine was the holy grail for a young, ambitious doctor. My debating partner in medical school, a Muslim named Abul Abbas, was a brilliant student. We had become best

friends, and his brilliance carried him directly from India to an internship at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, one of the most prestigious hospitals affiliated with Harvard. Abul Abbas kept in touch, regularly calling me with enviable tales about the paradise that was Boston and urging me to get there as quickly as possible.

It didn’t take long. When my year’s internship in New Jersey was completed, I secured a residency at a good place in Boston, thanks to Abul’s help. For the next two years I’d be working at the Lahey Clinic. It was a private hospital, which Abul called the Mayo Clinic of the East, with ties to Harvard even though it wasn’t an affiliated hospital like Brigham. Rita and I settled in the predominantly black section of Jamaica Plain, which had disturbingly high crime but also the only rents cheap enough for a struggling resident. What lay ahead was the hardest work of my life, harder than I could have imagined, even though I considered myself tireless—you had to be, if you wanted to keep playing the hero.

To augment my thousand dollars a month from Lahey, which mostly went toward the rent, I moonlighted at a suburban ER for four dollars an hour, which meant that I might go three or four days without sleep. Medical training in America was brutal. Our long shifts were supposed to make us think on our feet and to make the right decisions under stress. Because it was still in my character to obey authority without question, I didn’t ask how much good it did a patient if his doctor was semicomatose and mumbling his way through giving orders to the charge nurse. Exhaustion was no excuse. Anxiety about making the slightest mistake was a powerful incentive.

One day near the end of my two-year residency—I was now at the Boston VA Hospital, a vastly more frenetic and stressful environment than the posh private clinic I’d grown accustomed to—I went on my morning rounds. When I was an intern I couldn’t make a move without an attending physician’s permission, but residents can practice medicine independently once they get a state medical license. I had done that after my first six months in Massachusetts, adding hours of study to the grueling pace of work.

That morning I arrived at the bed of a patient who had suffered a

heart attack the day before. I scanned the chart and called over one of the nurses.

“Do you recognize this handwriting?” I asked, pointing to the patient’s chart. She gave me an odd look.

“It’s yours, isn’t it?”

I thought about it for a moment. “Yeah.”

According to the chart, I had resuscitated the man with CPR after his heart attack, intubated him, opened his chest, and put in a pacemaker.

It wasn’t that I hadn’t recognized my own handwriting; I simply couldn’t remember doing all those things or even having been there in the first place. This was very upsetting, but I couldn’t let on. With a reassuring smile, I got away from the nurse and only revealed my dismay to another resident, who had been pulling the same exhausting shifts. He shrugged.

“Don’t sweat it, man. That’s the whole point. If you survive the craziness, you can do the right thing in your sleep.”

When my parents heard that Rita was pregnant, they were overjoyed, but I had other, less welcome news. She would be flying back to India to have the baby. My father was bewildered that a doctor who had made it to hallowed Boston couldn’t afford to have his baby there. But when we moved to Massachusetts, Rita’s pregnancy was deemed a preexisting condition. Insurance wouldn’t cover it, but for $450—less than half the cost of paying for the delivery—we could buy Rita an Air India ticket to Delhi and back. I wasn’t willing to borrow money from my parents, and so when Rita was in her ninth month, barely a week from going into labor, I drove down to New York and saw her off at JFK. It was a difficult moment. I kept staring out the window until the plane was out of sight. Ultrasound exams for pregnant women were not in wide use then, but we had gotten one, and the doctor who ran the test was reasonably sure that it would be a girl.

I had had a bad scare earlier. When Rita went for a routine blood test, the pathologist called me up and said that her red blood cells looked abnormal, showing signs of anemia. This was not ordinary

anemia but a genetic condition called thalassemia, and if Rita had inherited it, so would our baby. I knew that children with thalassemia often died before reaching adulthood. I tried to control a sense of panic. The nearest medical library was in New York City—we hadn’t left yet for Boston—where I drove with the intention of immersing myself in reference books until I knew everything about this looming threat.

Rita’s red blood cells looked somewhat abnormal, but that didn’t mean that she or the baby was in danger. Thalassemia is caused by a recessive gene, and it takes both parents to be carriers for the full-blown disorder to appear. Even then, the chance of a baby being infected was 25 percent. I began to calm down. Statistics indicated that only 3 to 8 percent of Indians from our region had thalassemia. Since Rita had grown up normally, without slow development, bone deformation, or any other signs of thalassemia, our baby was safe. Rita probably had thalassemia as a trait in her genes but not the disease itself. The trait doesn’t need treatment since it causes no harm.

Once the threat receded, my curiosity was aroused. The Greek word for the sea is “

thalassa,

” and this gave thalassemia its name—it affects people of the Mediterranean (a separate strain exists in West Africa and other pockets around the world). How did a Mediterranean disease make it to India? The best guess is that it followed Alexander the Great on his long march of conquest to the East. In the summer of 325

BCE

he stood on the banks of the Indus River as the most powerful man in the world. He had taken eight years and marched his army from Macedonia three thousand miles to get there. Legend has it that he sat on the banks of the Indus and wept because there was no more world to conquer. (The truth is that his troops probably revolted and demanded that he turn back.)

A massive cultural change was underway. The West would seep into India in many waves, one invasion after another. Alexander would take Indians back home with him: astrologers, yogis, Ayurvedic physicians. The physicians added to Western medicine, it is surmised, since Greece was the cradle of ancient and medieval medicine in Europe. The astrologers and yogis were said to astonish the young

emperor with their knowledge. Alexander had only two more years to live before he died just shy of thirty-three in the royal palace in Babylon, still planning more military campaigns. He had his sights set on Arabia. Whether he was poisoned or died from a mysterious malady is debatable, but it’s almost a certainty that his army and a caravan of camp followers trailed thalassemia behind them. The rates for the disease are highest where they went, declining steadily as the army got farther away from the Mediterranean and mixed their genes with other peoples. Rita’s family came from the part of northwest India, later Pakistan, that lay directly in Alexander’s path. She carried history in her blood, which somehow made me feel a shiver of wonder.

After the birth took place at Moolchand, my father’s hospital, he phoned me to tell me that everything had gone smoothly. We had a baby girl. Rita was to stay in Delhi six weeks to ensure a full recovery before she and Mallika—whose name means flower—met me again at JFK. We drove back to Jamaica Plain, with an excited new father clutching the wheel and creating a road hazard since he couldn’t keep his eyes off his baby.

Our block in Jamaica Plain had seen an invasion of Indian doctors, all living in a row of dilapidated two-story brick houses. A shared culture and low rents bound us into a tight community. I was happy that Rita was saved from the aching loneliness of a resident’s wife who rarely spent time with her harassed husband. It also helped that we had the resilience of young people. (I disagree with Oscar Wilde’s famous quip that youth is wasted on the young. I couldn’t have survived without it.)

It comes as second nature to new immigrants to stay out of sight. Attracting attention feels like making yourself into a target. In this regard I was very different from the norm; I secretly envied one of our neighbors when he decided to show off his raise at work by buying a new Mustang. It made the desired impression. The wives agreed that it was a beautiful car; the husbands fumed in silence, knowing that their own cars had dropped two notches in pride. But we lived in an

area notorious for car thefts. The Mustang was stolen, not once but several times a month.

My task was to drive the owner to the police station after his Mustang was found. It inevitably was. The thieves would take it for a joy ride, and a few times the hubcaps were missing. After the fifth time in a month that I drove my neighbor to the impoundment lot, I’d had enough. He was already in a black mood, but I took a deep breath and said that I wasn’t doing this anymore. One last ride, and that was it. Which turned out to be prophetic: When we arrived at the facility, his car had been stolen from there. That was its destiny.

We tried to ignore how tenuous our personal safety was. One night I was driving home from the Lahey Clinic, which was then on Mass Ave., and at a stop I was too tired to move quickly when the light turned green. The car behind me honked, and my reaction must have been too slow for the driver, because he leaned out his window and started screaming. We exchanged rude hand gestures—I had learned that much in America—and I drove away. But in the rearview mirror I saw that he was following me. This was just a suspicion at first, but when I had made it all the way to Jamaica Plain, it became a certainty.

I pulled up to our apartment, ready for a confrontation. My pursuer stopped in the middle of the street, got out, and approached my car. My blood froze. The man had pulled out a handgun and was brandishing it wildly. With no time to think, I started flashing my headlights in his eyes and madly honking the horn. It was early in the morning. Suddenly windows flew open up and down the block. In each one, an Indian head stared down at the street.

My would-be assailant stopped and looked around. He was close enough that I heard him mutter something before he got back into his car and sped off.

“It’s your lucky day, s—thead.” Actually I was lucky to be from India at that moment. My welcome to America was complete.

12

..............

First Impressions

Sanjiv

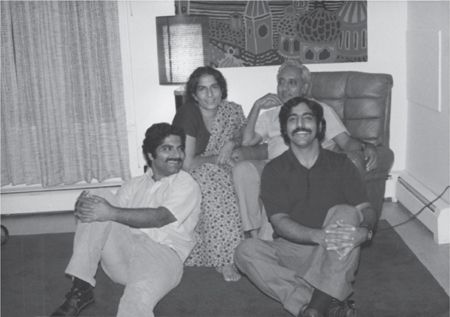

Deepak and Sanjiv’s parents visit Sanjiv’s apartment in Boston, 1973.

I

FOLLOWED DEEPAK’S PATH

to the West to complete my medical education. Our father’s generation had gone to England to complete their training, but there they had encountered a British ceiling. Indian doctors in England were allowed to rise to only a certain level, and when they returned to India they were behind their classmates in seniority and only rarely caught up. As a military physician my father was not subject to the same challenges. In medical school Amita and I saw almost everyone ahead of us graduating and heading for the United States. When people asked us what our plans were when we finished medical school, America was the obvious answer. It was sort of automatic: Graduate, pass the exam, and off you go to the United States.

For Amita and I there was an added consideration. During our studies Amita had given birth to our daughter, Ratika Priya Chopra, a beautiful little girl. We knew that our internship was going to be very difficult and time-consuming. We were both going to be on call at the hospital every third night and every third weekend. When we were scheduled to leave for America, Priya, as we called her, was more than a year old. We could either give up the opportunity to study in America or allow her to stay with her loving grandparents. My parents adored her. Although Deepak was older than me and had married a month before Amita and me, Priya was their first grandchild. We agreed on the sensible path. Priya would stay at home with my parents and join us in America as soon as possible.

Deepak had gone to America two years before we were eligible to go. Because long-distance phone calls from America to India were so prohibitively expensive—as much as forty-five dollars for three minutes—we rarely heard from him. On occasion he would call our parents to reassure them that he was fine. We did see Rita when she

returned home to give birth, but she didn’t tell us much about living in America.

Much of what I knew about America came from

Archie

and

Peanuts

comic books. Through these I knew that Americans liked hamburgers and milkshakes, and that kids in convertibles went to these hamburger joints. At school we were taught a subject called general knowledge. Just as we were taught math and science, we were taught the general knowledge that any educated person should have. It was in that class that I won the book about television, which I read and reread long before I actually saw any. But in GK we also studied America and Canada and, truthfully, my impression was that Canada was a better country. My impression of America was that the people who lived there worked very hard and were very rich. A book I read about Canada described beautiful farms, young people playing ice hockey, and people who were always friendly. Maybe they didn’t have as many cars or TV sets as Americans did, but the way they lived seemed more peaceful and less of a rat race. It just didn’t seem to me from afar that Americans were very happy people. Even at a young age I thought it would be fun to go to Canada, but I had no real thought of actually going anywhere. I considered myself very Indian. I was proud of the fact that I was receiving a wonderful education in the best schools in an exciting, independent country. India was changing and I expected to play my role in that change.