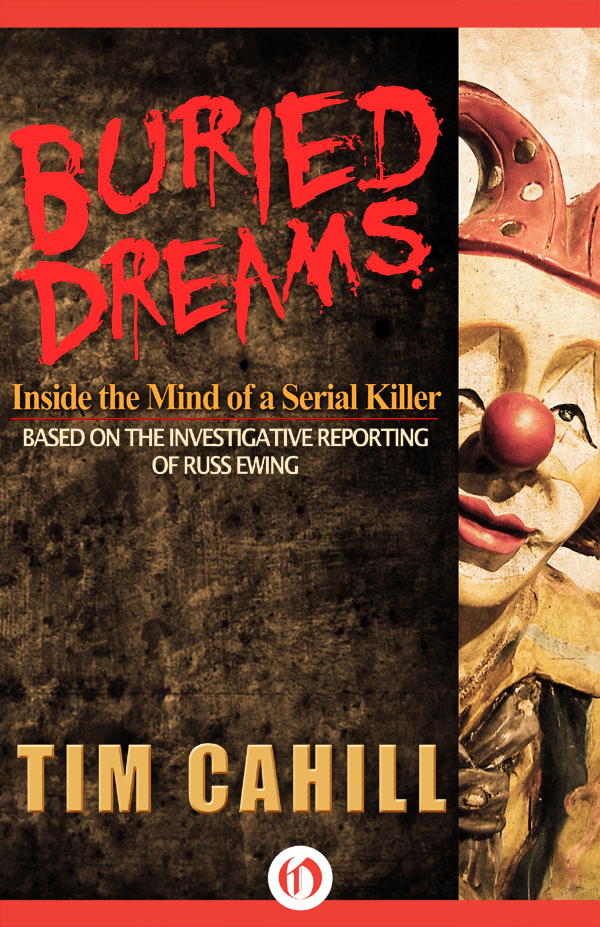

Buried Dreams

Authors: Tim Cahill

Inside the Mind of a Serial Killer

Tim Cahill

based on the investigative reporting of Russ Ewing

INTRODUCTION

A

HOT SEPTEMBER

MORNING

on the north side of Chicago. Russ Ewing and I were crouched over double, working with trenching tools under a three foot high ceiling and sweating heavily: two men digging in the mud of a crawl space under the porch of a north side home, hoping that we wouldn’t find what we half expected to uncover. Russ and I had reason to believe the body of a murdered boy was buried there in the hard-packed, yellow-brown mud.

We were partners, the two of us, working together on the story of John Wayne Gacy, America’s most prolific convicted mass murderer. Ewing is a reporter for WLS-TV in Chicago: a tough soft spoken man whose collegiate degree—unusual for a newsman—is in psychology.

In 1977, Ewing had done a report on missing children in Chicago. It seemed there were a disproportionate amount of young men, teenagers for the most part, reported missing from a neighborhood called Uptown. Russ Ewing didn’t know it then, but he was working on the story of John Wayne Gacy. A year later, Gacy was arrested, and charged with the murders of 33 young men. He had buried most of the victims in the crawl space under his house. Russ Ewing, who had done stories about several of the missing boys whose bodies were found in the wet mud under Gacy’s house, felt as if he knew those boys, and the Gacy story became a very personal one for him.

Reporting on the early stages of the murder trial, Ewing said, on camera, that “John Wayne Gacy must be considered innocent until proven guilty.” Mr. Gacy, who collected clippings

about himself and monitored news reports compulsively, apparently began to believe, on the strength of that statement, that the newsman was somehow “on my side.” He phoned Russ Ewing. The first contact led to prison interviews, protracted correspondence, and hundreds of dollars worth of collect calls from Gacy to Ewing.

In 1981, after working on the Gacy story, on and off, for four years, Ewing agreed to turn his information and the names of his contacts over to me for the purpose of writing a book. Russ would function as a consultant, providing information I might be unable to develop for myself. The actual writing was, by agreement, entirely my own.

A reporter is interested in facts. Early on, I discovered that, in addition to factual truth, I would be dealing with complex emotional and psychological nuances—information not easily reported in a two-minute news segment. During the next three and a half years, Russ and I worked together on the project, developing precisely this sort of information, retracing steps in his four year long investigation, speaking to people who had known Gacy both as a free man and a convict.

Mr. Gacy, for his part, provided information, dates, places, and the names of people we might contact. His motivation was muddy, at best, and he professed confusion concerning “the crimes.” At one point, Mr. Gacy suggested that there may have been more victims than the police knew about. Maybe, Mr. Gacy said, he didn’t actually commit any murders: perhaps they had been done by young employees of his contracting company. He recalled some of those employees working on his north side home, in the crawl space under a porch. The young men had dug a hole too deep for the work they were doing, and Gacy had seen it. Perhaps this was a grave. Perhaps there was a body buried there.

Mr. Gacy recalled the address—he has an extraordinary memory for such details—and described the house. Russ Ewing and I obtained permission from the owner to dig up the crawl space under his porch. Sometime during the third hour of work, we uncovered something ominous. It looked, in the dust, like the back of a man’s head. There was an odor of death that drove us from the crawl space.

Russ had three important telephone numbers in his notebook. They were written down in the precise order: Coroner, cops, camera crew.

“Do we call?” I asked Russ.

“Let’s be sure,” he said.

We put on painting masks to mute the smell. Kneeling by the hole, we brushed away the dust, careful not to destroy evidence. The hair didn’t seem to be human. It had a strange, coarse texture, and its color was odd: orange with streaks of black. I cleared away a bit more of the dirt with my shovel. We had uncovered a calico cat.

“Thank God,” I said. Only a cat.

Later Ewing told me he’d felt the same emotions that I had. There was horror at the core of it, of course, and revulsion, all of this mixed in with a sense that we’d been had, that we’d been blatantly manipulated. It was a combination of emotions I became entirely familiar with in the next few years.

“You could almost hear him laughing down in that crawl space,” I told Ewing.

“I know,” he said.

The reader should be aware at the outset that John Wayne Gacy has not and will not profit monetarily from this book. Nevertheless, Mr. Gacy has continued to talk with Russ Ewing and with other people who provided information to me. The latter sources are, by agreement, confidential. Why Mr. Gacy chose to cooperate with them, and with Russ Ewing, is a question I believe is fully answered in the narrative.

If the reader senses some uncertainty regarding motive here, it is because Mr. Gacy often contradicts himself, presents alternative explanations, or simply denies that he said something. Some psychologists and psychiatrists who have studied him think this tendency mirrors Mr. Gacy’s confusion, his underlying mental illness. Others state flatly that it is an attempt to “obfuscate,” to manipulate the listener, to “feign insanity.”

Whatever the case, John Gacy is a tireless talker. Sometimes he prefers to speak like a lout, and will litter the conversation with conscious double negatives, repetitive curses, and various tough-guy locutions. At other times, Mr. Gacy is positively pretentious in describing his own idealism. Almost simultaneously, he can play the sensitive “victim,” courageous enough to cry.

In analyzing what amounted to over 100 hours of interviews with Mr. Gacy, I concentrated on answering three

questions. First, what did he actually do—as opposed to what he said he did? How did he choreograph the killings, the central events of his life: was there significant ritual involved in the terrible danse macabre of death? Secondly, what was the facade that allowed him to literally get away with murder for almost six years? Finally, and most important, what was going on in his mind? How can such a man live with himself?

In constructing this book, I originally sought to find “the real John Gacy.” The idea was to subtract the lies, the misrepresentations, the false idealism. With the material available to me, I intended to identify internal contradictions, and work my way down into a solid core of truth. I was looking for a simple explanation. And yet . . . the more I studied Mr. Gacy, the more I came to realize that the apparent complexity of his personality defined him more accurately than any single theory I might formulate or propose. The “real John Gacy” is a creature composed of lies, internal contradictions, misrepresentations, and false idealism.

Buried Dreams,

then, mirrors my research method. In understanding the crimes committed by John Wayne Gacy, I found it was necessary to learn to think like John Wayne Gacy. This is neither pleasant nor entirely healthy. We are diving into some dark and chilly psychic waters here. The reader may feel claustrophobic, may feel trapped inside the killer’s mind, as I did in writing this book. Even so, it is the mind of the murderer—not murder itself—that ought to concern us.

In the three and a half years I spent writing and researching this book, I held one statistic in mind: the FBI estimates that there are at least 35 other serial killers at large in the United States today. In reviewing the literature on such multiple murderers I was struck by certain terrifying similarities. Among men like Jack the Ripper, Ted Bundy, and John Wayne Gacy there is a pattern that seems to repeat itself, a pattern, most professionals agree, that is too little studied and imperfectly understood.

Buried Dreams

is an attempt to isolate that pattern.

For this reason, I have tried to present a picture of a man’s mind, in his own style of speech, often in his own words. I wanted to put the reader inside that mind—the mind of the murderer—and that is why this book is written, for the most part, from Mr. Gacy’s point of view. I have endeavored to make his best case for him, as he would have

done. The reader might imagine himself or herself sitting across from Mr. Gacy in a prison conference room or a psychiatrist’s office.

John Gacy himself believes that “no one can tell when you’re lying and when you’re not,” at least in regard to such intangibles as motive. I am not so certain that this is true and

Buried Dreams

has been written in full confidence that the reader, like a smart cop or a good psychiatrist, will be able to see through the shifting ambiguities, to sweep away the “rationalizations” and “suppositions” until the soul of John Wayne Gacy lies bare.

From time to time, I have seen fit to intrude in order to set the record straight, to prevent libeling certain persons Mr. Gacy clearly wished to defame, and to provide information that he may have forgotten or purposely omitted. In some few cases, names have been changed to insure privacy, but all incidents are as Mr. Gacy related them, or as they were reported in the public record.

Some members of Chicago’s homosexual community have expressed fear that a book about John Wayne Gacy could result in a new wave of repression against gays. This is a legitimate concern, and one that compels me to state the perfectly obvious: for every serial killer who has preyed on men or boys, there is one who has stalked women and whose crimes have been essentially sexual in nature. Should heterosexuals be condemned because Ted Bundy is thought to have killed over 30 young women?

I suspect that the majority of readers—those whose lives never touched John Wayne Gacy’s—share, at the outset, my original belief that anyone committing such incomprehensibly cruel crimes must necessarily be insane. But if John Gacy is sane, as those who prosecuted him argued—if the pattern is not symptomatic of mental disease but is rather a rational criminal’s “method of operation"—we are confronted with an intensely disturbing moral and philosophical concept. It is not something we ordinarily care to examine too closely, this idea that evil exists in our world. Confronted with the crimes committed by John Wayne Gacy, decent people cling to the cold conceptual comfort of insanity. One psychologist I spoke with about Mr. Gacy stated this position best: “Evil is a medieval superstition.” Then again, that man never personally examined John Wayne Gacy, as the reader of this book is about to do.

T

IM

C

AHILL

CHAPTER 1

ONE OF THE NEIGHBORS

was wakened from her sleep by screams in the night: faint, high-pitched screams that drifted across the neatly mowed lawns and seemed to come from the house beyond a hedge she could see from her back door. It was hard to tell, on that humid summer night, when the air was still and thick as cotton, exactly where they were coming from, or even if they were nothing more than a remnant of troubled sleep, some dim, half-remembered nightmare. But no, fully awake now, she could hear them through the open window. They sounded like the cries of a boy, a fifteen-, sixteen-, seventeen-year-old boy: a young man about the same age as her son. The muffled screams went on and on, reaching a tormented crescendo that lasted for half an hour or more. “Drugs,” the woman thought. Maybe the boy was taking drugs, and maybe the drugs made him scream. Could drugs make boys scream like that?

She called the police and reported the disturbance, which, as near as she could tell, seemed to be coming from the house behind hers out in Norwood Park, an unincorporated area north and west of Chicago. Officers visited the house at 8213 Summerdale, where they talked with the owner, a contractor named John Gacy. Nothing seemed to be amiss.

There were other nights, almost always weekend nights, when the woman woke to screams across the lawn in the still of the night, but the police had investigated, and there was never anything on the radio or television about foul play in Norwood Park.

Several months later, on the night of December 11,

1978, a fifteen-year-old boy was reported missing by his worried parents. Rob Piest was an A student, a standout gymnast, an ambitious, intelligent boy who was very close to his family—not at all the sort of kid who runs away from home. Certainly not at nine o’clock in the evening, after putting in four hours on his part-time job; certainly not on the night of his mother’s forty-sixth-birthday party, a party that had been postponed until Rob finished work. The boy was last seen on his way to talk to a contractor about a summer job. The contractor’s name was John Gacy. That night, Rob Piest simply disappeared.

Suburban Des Plaines police, investigating the case, put a tracer on John Wayne Gacy, Jr., and found that he had been convicted of sodomy, in Iowa, ten years previous. That offense had involved a fifteen-year-old boy.

Ten days later, after an intensive investigation, John Gacy was arrested. He insisted that he knew nothing about the Piest boy’s disappearance. The interrogation was cut short when the suspect complained of severe chest pains and said that he had a history of heart trouble. Officers rushed Gacy to Holy Family Hospital in Des Plaines.

Meanwhile, a search warrant was obtained for Gacy’s house. Officers and evidence technicians—representatives of the Des Plaines police department, the Cook County sheriffs police, and the state’s attorney’s detail—began arriving at the brick ranch house about seven that night. They were looking for evidence of a kidnapping; they feared they might find evidence of a murder.

The front room of the house at 8213 Summerdale was choked with plants, and there were several pictures of sad-faced clowns on the wall. In a business office just off the living room, officers found several sets of meticulous records detailing Gacy’s business, as well as photos showing the chunky contractor shaking hands with the mayor of Chicago and with the wife of the President of the United States. In a rec room, hidden near the pool table, officers found a large vibrating dildo crusted with disagreeable evidence that it had been used in some recent anal penetration. There were a number of books and magazines about homosexuality, and several of them featured older men in congress with young boys. Ominously, in the attic, investigators found some wallets, and the information inside proved that they belonged to young men, teenagers.

Toward the front of the house, in a living-room closet, police found a trapdoor leading down into a dark, dirt-floored crawl space, which seemed to be flooded. The beam of a floodlight pointed into the open hatchway was reflected on the surface of the dank water that stood a foot deep below. Cook County evidence technician Daniel Genty saw a cord just under the hatchway door; he plugged the cord into a nearby socket. There was a rumble of machinery, and a sump pump, somewhere in the murky depths, began pumping water out of the darkness. A dank, putrid smell emanated from the crawl space: the smell of sewage and something worse, something officers recognized as the odor of a morgue.

It took about fifteen minutes for the crawl space to drain, and in that time, evidence technicians searching the garage and workshed found a number of wallets containing IDs belonging to several young men, as well as some items of personal jewelry a teenage boy might wear. It didn’t seem possible that all these boys had just happened to leave their clothes, their jewelry, and their wallets at John Gacy’s house.

Daniel Genty now had an idea of what he might find in the crawl space. When the water had been flushed away, Genty dropped through the hatchway, into the mud. There was no ladder: the crawl space was only about two and a half feet deep. Genty dragged a small shovel and fire department floodlight with him. He crawled, on his hands and knees, toward the south wall, dropping to his belly to get under the center-support beam that ran the length of the house. In the southeast corner of the house, up against the foundation, Genty could see two long depressions, parallel to the wall. They were about six feet long and a foot and a half wide: the size of graves.

Genty crawled to the northwest corner of the crawl space, then moved to the southwest, where he noted three small puddles, about the size of ashtrays. One of the puddles was a dark, murky, purple color. The other two were filled with hundreds of thin red worms, about two inches long, and when Genty shone the floodlight on them, they burrowed into the soft mud.

It was there, in the southwest corner of the crawl space, that Genty decided to make his first excavation. He knelt, nearly doubled over, and plunged his trenching tool into the mud. An unbearably putrid odor burst up out of the earth and filled the crawl space. The second shovelful of earth

contained a clot of adipocere: white, soapy, rotting flesh, almost like lard. A product of decomposition, adipocere takes twelve months or more to form. The body could not be Rob Piest’s.

Gacy, it seemed, could possibly be guilty of more than one murder. Genty took one last scoop of mud, hit something hard, and pried up what looked like a human arm bone. Skeletal remains: definitely not the body of a boy last seen alive eleven days ago.

Genty shouted to Lieutenant Joseph Kozenczak of the Des Plaines Police Department upstairs: “Charge him! Murder!”

Kozenczak yelled, “Repeat that!”

“I found one.”

“Is it Piest?”

“No. I don’t think so. It’s been here too long.”

Another evidence technician and an investigator dropped into the crawl space.

The odor, in that damp and confined area, was almost as unbearable as the thought of what the crawl space contained. “I think this place is full of kids,” Genty said.

In the northeast corner of the crawl space under John Gacy’s house, the officers found more puddles, all swarming with thin red worms. There, two feet from the north wall, they uncovered what appeared to be a knee bone. The flesh was so desiccated that at first they thought it was blue-jean material.

South of that dig, Genty uncovered some human hair in the soil. The second evidence technician dug along the south wall and found two long bones, human leg bones, both very blackened. Rather than disturb any more remains that might complicate identification procedures or destroy evidence, the officers decided to quit the crawl space and call the coroner.

At about the same time, John Gacy was being released from Holy Family Hospital. He had been thoroughly examined, and doctors could find no evidence of a heart attack. Gacy’s pulse was a little high, that was all. Under heavy guard—detectives had been told what the search uncovered—Gacy was returned to the Des Plaines police station, where he was arrested and charged with murder.

Gacy signed a card waiving his Miranda rights, then spoke to detectives David Hachmeister and Michael Albrecht.

“My house,” Gacy said. “Did you go into the crawl space?”

“Yeah,” Albrecht said, “we did.”

“I used lime,” Gacy said. “That’s what it was for.”

“What was it for, John?” Albrecht asked.

“For the sewage, the dampness . . . for . . . what you found there.”

A mug shot, taken at the time, shows a stuporous, uncomprehending man. Gacy’s puffy face and undistinguished features look slack, as if the bones of his skull have no substance to them. He stares into the camera, and his eyes are glassy, dull, and dead. He looks like a man insane. Or on drugs.

“There are four Johns,” Gacy told Albrecht. “I don’t know all of them.” One of the four, Gacy explained later, was called “Jack.” Jack didn’t like homosexuality, and he detested homosexuals. The bodies in the crawl space? You’d have to ask Jack how they died. John did the dirty work. John, it seemed, had been forced to cover for Jack, to bury the bodies, to live with the stench, to spread the lime.

In a second voluntary statement, given about three-thirty the next morning, Gacy said there were “twenty-five to thirty bodies.” Detectives found that number hard to comprehend, and they questioned Gacy closely. The suspect said he couldn’t answer every question. Some things, he said, he just honestly didn’t know. “You’d have to ask Jack that,” he explained.

Piest’s body, Gacy said, had been thrown from a bridge on I-55 into the Des Plaines River. Jack was working too fast for John to keep up. The crawl space was full, and John, with his worsening heart condition, couldn’t dig any more graves.

The killer was named Jack: Jack Hanley.

John could tell the police that much.

The next morning, a fleet of police vehicles and nearly three dozen officers, including representatives from three different law-enforcement agencies, invaded Norwood Park. They were closely followed by about as many reporters.

The media were hungry and the suspect was in custody, unavailable. As is usual in such cases, the neighbors were interviewed about the accused killer who had lived in their midst. No one could believe it, not at first. The man had a heart condition, after all: how could he have dug those graves, doubled over in that cramped crawl space? He was 5 feet 8 and weighed over 230 pounds.

There was an odd sense of

déjà vu

about these postarrest

interviews with the accused killer’s friends and neighbors. It was a scene that had been played in 1971 in Yuba City, California, when Juan Corona was arrested and charged with the murders of twenty-five young farm workers, all males; a scene that had its run in Houston, when Elmer Wayne Henley was charged with the sex-torture murders of twenty-seven young men. It was a scene that would play in Atlanta in 1981, when Wayne B. Williams was arrested and charged with the murders of two young blacks. Prosecutors insisted they could link Williams with the murders of twenty-eight young men. Eighty young men dead in all: Eighty murders, all of them, so it seemed, committed in some insane sexual frenzy or in a calculated effort to conceal evidence of homosexual activity.

These were not mass murders, journalists pointed out. It was a problem of semantics, as well as a difference in method. Richard Speck—who invaded the Chicago living quarters of eight nurses in 1966 and murdered seven—was a mass murderer. The slaughter had been accomplished in a matter of hours, all at once. Charles Whitman, who climbed a tower at the University of Texas and shot twelve in 1966, was a mass murderer. Henley, Corona, and later Williams were not mass murderers in that sense; they were serial killers. All three seemed to lead normal lives, and they killed their victims one at a time, as the mood struck them, over a period of years. The serial killer was a colder, more calculating animal than the mass murderer. Part of the serial killer’s method was façade, the ability to live an apparently normal life between, and in spite of, the accumulating murderous episodes. The serial killer is everyone’s next-door neighbor.

Serial murderers survive and kill, and get away with the killings, in part because life does not emulate art. It is not the way we expect it to be, not as it is on TV or in the movies, where discordant music hints at some character’s frightening psychological problems, where low camera angles and shadowed lighting can suggest an impending homicide. The serial murderers lived next door, or across the street, or down the block. They talked and walked and laughed like any other man, but they killed, and killed again—and again, and again after that—until they were caught.

Normal-enough guys; pretty good neighbors; bright, friendly fellows. And when they were caught, their neighbors found themselves squinting into bright television lights, feeling defensive, as if they had to justify themselves; feeling

angry or confused; feeling somehow betrayed. The killer, in his frenzy, had destroyed something soul deep in those who lived around him. The viewer sensed it in the troubled glance off camera; the facial tic; the odd, inappropriate gesture: these were innocent people destined to live with a sickly sad, unearned guilt the rest of their lives.

No, the neighbors and friends said in California, there didn’t seem to be anything troubling Juan. I never thought he might have homosexual tendencies. Never had an inkling. In Atlanta, they would say that Wayne was a bright young man, destined to go places. Elmer Henley was a hard worker, they said in Texas. The neighbors were numb in Texas, stunned in California, staggered in Georgia.

It was no different in Chicago. The day the story broke, there were shots, broadcast live, of the brick ranch house with the outdoor Christmas lights mysteriously blinking (the owner, after all, was in jail), and the neighbors, in voice-over—or on the radio, or in newspaper columns—described the man who had lived there as gregarious, community-minded, generous. When the snow piled up on the streets, they said, John Gacy hooked up a snowplow and cleared the driveways up and down his block. He had worked long and hard to get streetlights installed in unincorporated Norwood Park. He was a man said to have important political connections, and some neighbors had seen, in the office in his home, those pictures of John Gacy shaking hands with the mayor of Chicago, with the wife of the President of the United States. He was a man who gave an annual summer lawn party for four hundred or more people, at his own expense; a man who organized Chicago’s Polish Day parade and saw that it ran like clockwork. And this—on his own time, and at no pay, John Gacy went to hospitals where he entertained sick children, dressed as a clown. Pogo the clown.