Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (33 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

Major Jackson said he was not there to make trouble. Then he ordered Jack to assemble his men in front of the soldiers.

As soon as this was done, the major pointed to a bunch of sagebrush at the end of the formation. “Lay your gun here,” he commanded.

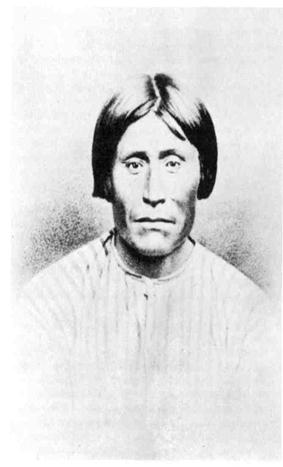

17. Captain Jack, or Kintpuash, Having the Water Brash. Photographed by L. Heller in 1873. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

“What for?” Jack asked.

“You are the chief. You lay your gun down, all your men will do the same. You do that, and we’ll have no trouble.”

Captain Jack hesitated. He knew his men would not want to give up their arms. “I have never fought white people yet,” he said, “and I do not want to.”

The major insisted that they give up their guns. “I won’t let anyone hurt you,” he promised.

Captain Jack placed his gun on the sagebrush and signaled the others to do as he had done. They stepped up one by one, stacking their rifles. Scarfaced Charley was the last. He laid his rifle on top of the pile, but kept his pistol strapped around his waist.

The major ordered him to hand over the pistol.

“You got my gun,” Scarfaced replied.

The major called to Lieutenant Frazier Boutelle: “Disarm him!”

“Give me that pistol, damn you, quick!” Boutelle ordered as he stepped forward.

Scarfaced Charley laughed. He said he was not a dog to be shouted at.

Boutelle drew his revolver. “You son-of-a-bitch, I’ll show you how to talk back to me.”

Scarfaced repeated that he was not a dog, adding that he would keep his pistol.

3

As Boutelle brought his revolver into firing position, Scarfaced quickly drew his pistol from his belt. Both men fired at the same time. The Modoc’s bullet tore through the lieutenant’s coat sleeve. Scarfaced was not hit. He swung toward the stack of arms, sweeping his rifle from the top, and every Modoc warrior followed his example. The cavalry commander ordered his men to open fire. For a few seconds there was a lively exchange of shots, and then the soldiers retreated, leaving one man dead and seven wounded on the field.

By this time the Modoc women and children were in their log dugouts, paddling southward for Tule Lake. Captain Jack and

his warriors followed along the shore, keeping hidden in the thick reeds. They were heading for the Modocs’ legendary sanctuary south of the lake—the California Lava Beds.

The Lava Beds was a land of burned-out fires that had turned into rocky fissures, caves, and crevices. Some of the ravines were a hundred feet deep. The cave which Captain Jack chose as his stronghold was a craterlike pit surrounded by a network of natural trenches and lava-rock breastworks. He knew that his handful of warriors could fight off an army if necessary, but he hoped the soldiers would leave them alone now. Surely the white men would not want these useless rocks.

When Major Jackson’s soldiers had come to Captain Jack’s camp, a small band of Modocs led by Hooker Jim was camped on the opposite side of Lost River. In the early hours of the morning while Captain Jack was fleeing with his people for the Lava Beds, he had heard gunfire from the direction of Hooker Jim’s camp. “I ran off and did not want to fight,” he said afterward. “They shot some of my women, and they shot my men. I did not stop to inquire anything about it, but left and went away. I had very few people and did not want to fight.”

4

Not for a day or two did he discover what had happened to Hooker Jim’s people. Then suddenly Hooker Jim appeared outside Jack’s stronghold. With him were Curly Headed Doctor. Boston Charley, and eleven other Modocs. They told Jack that at the time soldiers came to his camp, several settlers had come to their camp and started shooting at them. These white men shot a baby out of its mother’s arms, killed an old woman, and wounded some of the men. On their way to the Lava Beds, Hooker Jim and his men decided to avenge the deaths of their people. Stopping briefly at isolated ranch houses along the way, they had killed twelve settlers.

At first Jack thought Hooker Jim was merely boasting, but the others said it was true. When they named the dead white men, Jack could not believe it. Some of them were settlers he knew and trusted. “What did you kill those people for?” he demanded. “I never wanted you to kill my friends. You have done it on your own responsibility.”

5

Captain Jack knew for certain now that the soldiers would

be coming; even into the vastnesses of the Lava Beds they would come for revenge. And because he was chief of the Modocs he would have to answer for the crimes of Hooker Jim and the others.

Not until the Ice Moon did the soldiers come. On January 13, 1873, the Modocs guarding the outer defense ring sighted a Bluecoat reconnaissance party approaching a bluff overlooking the Lava Beds. The Modocs drove them away with a few long-distance shots. Three days later a force of 225 regular soldiers supported by 104 Oregon and California Volunteers came riding like ghosts through the fog of a wintry afternoon. They took positions along ridges facing Captain Jack’s stronghold, and as darkness fell they began building sagebrush fires to keep warm. The military commanders were hopeful that if the Modocs saw the force arrayed against them, they might come in and surrender.

Captain Jack was in favor of surrendering. He knew that the soldiers most of all wanted the Modocs who had killed the settlers, and he was willing to put his life along with theirs in the hands of the soldier chiefs rather than sacrifice the lives of all his people in a bloody battle.

Hooker Jim, Curly Headed Doctor, and those who had killed the settlers were opposed to any surrender, and they forced Jack to call a council to vote on what action the tribe should take. Of the fifty-one warriors in the stronghold, only fourteen wanted to surrender. Thirty-seven voted to fight the soldiers to the death.

Before daylight on the seventeenth, they could hear the soldiers’ bugles echoing across the fog-shrouded Lava Beds. Not long afterward, howitzers sounded the beginning of the Bluecoat attack. The Modocs were ready for them. Camouflaged with sagebrush head coverings, they moved in and out of crevices, picking off soldiers in the first skirmish line.

By midday the attackers were spread out for more than a mile, their communications badly broken because of fog and terrain. Keeping under cover, the Modoc warriors hurried back and forth along the front, creating an illusion of superiority of numbers. When one company of soldiers moved up close to the stronghold, the Modoc fire concentrated upon it, the women

joining the warriors in the shooting. Late in the day, Jack and Ellen’s Man led a charge that routed the soldiers, who left their casualties on the field.

Just before sunset the fog lifted, and the Modocs could see the soldiers retreating to their camp on the ridge. The warriors went out to where the dead Bluecoats were lying, and found nine carbines and six belts of cartridges. Farther on were more ammunition and some Army rations that had been thrown away by the fleeing soldiers.

When darkness came the Modocs built a big fire and celebrated. None had been killed in the fighting, and none was seriously wounded. They had captured enough rifles and ammunition to fight another day. Next morning they were ready for the soldiers, but when the soldiers came there were only a few of them, and they were carrying a white flag. They wanted to recover their dead. Before the end of that day all the soldiers were gone from the ridge.

Believing that the Bluecoats would return, Captain Jack kept scouts far out to watch for them. But the days passed one after the other, and the soldiers stayed far away. (“We fought the Indians through the Lava Beds to their stronghold,” the commander of the attacking force reported, “which is the center of miles of rocky fissures, caves, crevices, gorges, and ravines. … One thousand men would be required to dislodge them from their almost impregnable position, and it must be done deliberately, with a free use of mortar batteries. … Please send me three hundred foot-troops at the earliest date.”

6

)

On February 28, Captain Jack’s cousin, Winema, came to the Lava Beds. Winema was married to a white man named Frank Riddle, and he and three other white men accompanied her. These men had been friendly to the Modocs in the time when they visited freely in Yreka. Winema was a cheerful, energetic, round-faced young woman who now called herself Toby Riddle. She had adopted the ways of her husband, but Jack trusted her. She told him that she had brought the white men to have a talk with him, and that they intended to spend the night in the stronghold to prove their friendship. Jack assured her that they were welcome and that no harm would come to any of them.

In the council which followed, the white men explained that

the Great Father in Washington had sent out some commissioners who wanted to talk peace. The Great Father hoped to avoid a war with the Modocs, and he wanted the Modocs to come and talk with the commissioners so that they could find a way to peace. The commissioners were waiting at Fairchild’s ranch not far from the Lava Beds.

When the Modocs raised the question of what would happen to Hooker Jim’s band for killing the Oregon settlers, they were told that if they surrendered as prisoners of war they would not be subject to trial by Oregon law. Instead they would be taken far away and placed on a reservation in one of the warm places—Indian Territory or Arizona.

“Go back and tell the commissioners,” Jack replied, “that I am willing to hear them in council and see what they have got to offer me and my people. Tell them to come to see me, or send for me. I will go and see them if they will protect me from my enemies while I am holding these peace councils.”

7

Next morning the visitors departed, Winema promising that she would inform Jack when the time and place for the council was decided. On that same day Hooker Jim and his followers slipped away to Fairchild’s ranch, sought out the commissioners, and declared that they wanted to surrender as prisoners of war.

The members of the peace commission were Alfred B. Meacham, who had once been the Modocs’ agent in Oregon; Eleazar Thomas, a California clergyman; and L. S. Dyar, a subagent from the Klamath reservation. Overseeing their activities was the commander of the troops gathered outside the Lava Beds, General Edward R. S. Canby—the same Canby who as an Eagle Chief had fought and made peace with Manuelito’s Navahos twelve years earlier in New Mexico. (See

Chapter 2

.)

When Hooker Jim’s Modocs came into Canby’s headquarters with their startling announcement of surrender, the general was so delighted that he dispatched a hasty telegram to the Great Warrior Sherman in Washington, informing him that the Modoc war was ended and requesting instruction as to when and where he should transport his prisoners of war.

In his excitement Canby failed to put Hooker Jim and his eight followers under arrest. The Modocs wandered out into the military camp to have a closer look at the soldiers who were

now supposed to protect them from the citizens of Oregon. During their rounds, they happened to meet an Oregon citizen who recognized them and threatened to have them arrested for murdering settlers on Lost River. The governor of Oregon had demanded their blood, he said, and as soon as the governor got his hands on them the law would hang them.

At the first opportunity, Hooker Jim and his band mounted their horses and rode as fast as they could back to the Lava Beds. They warned Captain Jack not to go to Fairchild’s ranch to meet the commissioners; the proposed council was a trap to catch the Modocs and send them back to Oregon to be hanged.

During the next few days, as Winema and Frank Riddle came and went with messages, the suspicions of Hooker Jim’s Modocs proved to be true insofar as they were concerned. Political pressure from Oregon forced General Canby and the commissioners to withdraw their offer of amnesty to Hooker Jim’s band. Captain Jack and the remainder of the Modocs, however, were free to come in and surrender with a guarantee of protection.

Captain Jack was now caught in a classic dilemma. If he abandoned Hooker Jim’s people, he could save his own. But Hooker Jim had come to him for protection under the chieftainship of the Modocs.

On March 6, with the help of his sister Mary, Jack wrote a letter to the commissioners, and she delivered it to Fairchild’s ranch. “Let everything be wiped out, washed out, and let there be no more blood,” he wrote. “I have got a bad heart about those murderers. I have got but a few men and I don’t see how I can give them up. Will they give up their people who murdered my people while they were asleep? I never asked for the people who murdered my people. … I can see how I could give up my horse to be hanged; but I can’t see how I could give up my men to be hanged. I could give up my horse to be hanged, and wouldn’t cry about it, but if I gave up my men I would have to cry about it.”

8

Canby and the commissioners, however, still wanted to meet Captain Jack and persuade him that war for his people would be worse than surrendering the killers. Even though the Great Warrior Sherman advised Canby to use his soldiers against the

Modocs so “that no other reservation for them will be necessary except graves among their chosen Lava Beds,” the general kept his patience.

9