Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (58 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

Geronimo later explained it this way: “Sometime before I left, an Indian named Wadiskay had a talk with me. He said, ‘They are going to arrest you,’ but I paid no attention to him, knowing that I had done no wrong; and the wife of Mangas, Huera, told me that they were going to seize me and put me and Mangas in the guardhouse, and I learned from the American and Apache soldiers, from Chato, and Mickey Free, that the Americans were going to arrest me and hang me, and so I left.”

13

The flight of Geronimo’s party across Arizona was a signal for an outpouring of wild rumors. Newspapers featured big headlines: THE APACHES ARE OUT! The very word “Geronimo” became a cry for blood. The “Tucson Ring” of contractors,

seeing a chance for a profitable military campaign, called on General Crook to rush troops to protect defenseless white citizens from murderous Apaches. Geronimo, however, was desperately trying to avoid any confrontation with white citizens; all he wanted to do was speed his people across the border to the old Sierra Madre sanctuary. For two days and nights the Chiricahuas rode without making camp. Along the way, Chihuahua changed his mind about going to Mexico; he turned his band off the trail, intending to return to the reservation. Pursuing soldiers caught up with Chihuahua, forced him into a fight, and started him on a bloody trail of plundering before he could cross into Mexico. Every assault he committed was blamed on Geronimo, because few Arizonans had ever heard of Chihuahua.

Crook meanwhile was trying to avoid the vast military operation that the Tucson Ring and their political friends in Washington were demanding of him. He knew that personal negotiation was the only way to deal with three dozen Apache warriors. For the benefit of local citizens, however, he ordered a few cavalrymen to march out of each fort under his command, but he depended entirely on his trusted Apache scouts to find the resistant Chiricahuas. He was gratified that Chato and Cochise’s younger son, Alchise, both volunteered to search for Geronimo.

As autumn approached, it was clear that Crook once again would have to cross the border into Mexico. His orders from Washington were explicit: kill the fugitives or take their unconditional surrenders.

By this time the Chiricahuas had discovered that units of the Mexican Army were waiting for them in the Sierra Madres. Caught between Mexicans who wanted only to kill them and Americans who were willing to make prisoners of them, Geronimo and the other leaders finally decided to listen to Chato and Alchise.

On March 25, 1886, the “hostile” Apache chiefs met with Crook a few miles south of the border at Canon de los Embudos. After three days of emotional speech making, the Chiricahuas agreed to surrender. Crook then told them they must surrender without conditions, and when they asked what that meant, he told them frankly that they would probably be taken far away

to the East, to Florida, to become prisoners. They replied that they would not surrender unless the Gray Wolf would promise that they would be returned to their reservation after two years of imprisonment. Crook thought the proposition over; it seemed fair to him. Believing that he could convince Washington that such a surrender was better than no surrender, he agreed.

“I give myself up to you,” Geronimo said. “Do with me what you please. I surrender. Once I moved about like the wind. Now I surrender to you and that is all.”

Alchise closed the council with a plea to Crook to have pity on his erring Chiricahua brothers. “They are all good friends now and I am glad they have surrendered, because they are all the same people—all one family with me; just like when you kill a deer, all its parts are of the one body; so with the Chiricahuas. … Now we want to travel along the open road and drink the waters of the Americans, and not hide in the mountains; we want to live without danger or discomfort. I am very glad that the Chiricahuas surrendered, and that I have been able to talk for them. … I have never told you a lie, nor have you ever told me a lie, and now I tell you that these Chiricahuas really want to do what is right and live at peace. If they don’t then I lie, and you must not believe me anymore. It’s all right; you are going ahead to Fort Bowie; I want you to carry away in your pocket all that has been said here today.”

14

Convinced that the Chiricahuas would come into Fort Bowie with his scouting troop, Crook hurried on there to telegraph the War Department in Washington the terms he had given the Chiricahua chiefs. To his dismay a reply came back: “Cannot assent to the surrender of the hostiles on the terms of their imprisonment East for two years with their understanding of their return to the reservation.”

15

The Gray Wolf had made another promise he could not keep. As a crowning blow, he heard the next day that Geronimo and Naiche had broken away from the column a few miles below Fort Bowie and were fleeing back into Mexico. A trader from the Tucson Ring had filled them full of whiskey and lies about how the white citizens of Arizona would surely hang them if they returned. According to Jason Betzinez, Naiche got drunk and fired his gun in the air. “Geronimo thought that fighting had broken out with the troops. He and

Naiche stampeded, taking with them some thirty followers.” Perhaps there was more to it than that. “I feared treachery,” Geronimo said afterward, “and when we became suspicious, we turned back.” Naiche later told Crook: “I was afraid I was going to be taken off somewhere I didn’t like; to some place I didn’t know. I thought all who were taken away would die. … I worked it out in my own mind. … We talked to each other about it. We were drunk … because there was a lot of whiskey there and we wanted a drink, and took it.”

16

As a result of Geronimo’s flight, the War Department severely reprimanded Crook for his negligence, for granting unauthorized surrender terms, and for his tolerant attitude toward Indians. He immediately resigned and was replaced by Nelson Miles (Bear Coat), a brigadier general eager for promotion.

Bear Coat took command on April 12, 1886. With full support from the War Department, he quickly put five thousand soldiers into the field (about one-third of the combat strength of the Army). He also had five hundred Apache scouts, and thousands of irregular civilian militia. He organized a flying column of cavalrymen and an expensive system of heliographs to flash messages back and forth across Arizona and New Mexico. The enemy to be subdued by this powerful military force was Geronimo and his “army” of twenty-four warriors, who throughout the summer of 1886 were also under constant pursuit by thousands of soldiers of the Mexican Army.

In the end it was the Big Nose Captain (Lieutenant Charles Gatewood) and two Apache scouts, Martine and Kayitah, who found Geronimo and Naiche hiding out in a canyon of the Sierra Madres. Geronimo laid his rifle down and shook hands with the Big Nose Captain, inquiring calmly about his health. He then asked about matters back in the United States. How were the Chiricahuas faring? Gatewood told him that the Chiricahuas who surrendered had already been shipped to Florida. If Geronimo would surrender to General Miles, he also would probably be sent to Florida to join them.

Geronimo wanted to know all about Bear Coat Miles. Was his voice harsh or agreeable to the ear? Was he cruel or kind-hearted? Did he look you in the eyes or down at the ground when he talked? Would he keep his promises? Then he said to

Gatewood: “We want your advice. Consider yourself one of us and not a white man. Remember all that has been said today, and as an Apache, what would you advise us to do under the circumstances?”

“I would trust General Miles and take him at his word,” Gatewood replied.

17

And so Geronimo surrendered for the last time. The Great Father in Washington (Grover Cleveland), who believed all the lurid newspaper tales of Geronimo’s evil deeds, recommended that he be hanged. The counsel of men who knew better prevailed, and Geronimo and his surviving warriors were shipped to Fort Marion, Florida. He found most of his friends dying there in that warm and humid land so unlike the high, dry country of their birth. More than a hundred died of a disease diagnosed as consumption. The government took all their children away from them and sent them to the Indian school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and more than fifty of their children died there.

Not only were the “hostiles” moved to Florida, but so were many of the “friendlies,” including the scouts who had worked for Crook. Martine and Kayitah, who led Lieutenant Gatewood to Geronimo’s hiding place, did not receive the ten ponies promised them for their mission; instead they were shipped to imprisonment in Florida. Chato, who had tried to dissuade Geronimo from leaving the reservation and then had helped Crook find him, was suddenly removed from his

rancho

and sent to Florida. He lost his land allotment and all his livestock; two of his children were taken to Carlisle, and both died there. The Chiricahuas were marked for extinction; they had fought too hard to keep their freedom.

But they were not alone. Eskiminzin of the Aravaipas, who had become economically independent on his Gila ranch, was arrested on the charge of communicating with an outlaw known as the Apache Kid. Eskiminzin and the forty surviving Aravaipas were sent to live with the Chiricahuas in Florida. Later, all these exiles were transferred to Mount Vernon Barracks, Alabama.

Had it not been for the efforts of a few white friends such as George Crook, John Clum, and Hugh Scott, the Apaches soon would have been driven into the ground at that fever-ridden

post on the Mobile River. Over the objections of Bear Coat Miles and the War Department, they succeeded in having Eskiminzin and the Aravaipas returned to San Carlos. The citizens of Arizona, however, refused to admit Geronimo’s Chiricahuas within the state. When the Kiowas and Comanches learned of the Chiricahuas’ plight from Lieutenant Hugh Scott, they offered their old Apache enemies a part of their reservation. In 1894 Geronimo brought the surviving exiles to Fort Sill. When he died there in 1909, still a prisoner of war, he was buried in the Apache cemetery. A legend still persists that not long afterward his bones were secretly removed and taken somewhere to the Southwest—perhaps to the Mogollons, or the Chiricahua Mountains, or deep into the Sierra Madres of Mexico. He was the last of the Apache chiefs.

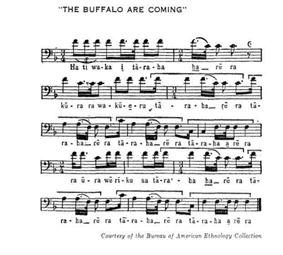

Listen, he said, yonder the buffalo are coming,

These are his sayings, yonder the buffalo are coming,

They walk, they stand, they are coming,

Yonder the buffalo are coming.

Dance of the Ghosts

1887

—

February 4,

U.S. Congress creates Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate railroads. June 21, Britain celebrates Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. July 2–4, Union and Confederate veterans hold reunion at Gettysburg.1888

—

May 14,

Brazil abolishes slavery. November 6, Grover Cleveland receives more popular votes than Benjamin Harrison, but Harrison wins Presidency by electoral votes.1889

—

March 4,

Benjamin Harrison inaugurated as President. March 23, President Harrison opens Oklahoma (former Indian Territory) to white settlement. March 31, Eiffel Tower is completed in Paris. May 31, five thousand lose lives in Johnstown Flood. November 2–11, North and South Dakota, Montana, and Washington become states of the Union.1890

—

January 25,

Nellie Bly wins race around the world in 72 days, 6 hours, and 11 minutes. June 1, population of United States reaches 62,622,250. July 3–10, Idaho and Wyoming become forty-third and forty-fourth states of the Union.If a man loses anything and goes back and looks carefully for it he will find it, and that is what the Indians are doing now when they ask you to give them the things that were promised them in the past; and I do not consider that they should be treated like beasts, and that is the reason I have grown up with the feelings I have. … I feel that my country has gotten a bad name, and I want it to have a good name; it used to have a good name; and I sit sometimes and wonder who it is that has given it a bad name.

—

TATANKA YOTANKA (SITTING BULL)Our land here is the dearest thing on earth to us. Men take up land and get rich on it, and it is very important for us Indians to keep it.

—

WHITE THUNDERAll Indians must dance, everywhere, keep on dancing. Pretty soon in next spring Great Spirit come. He bring back all game of every kind. The game be thick everywhere. All dead Indians come back and live again. They all be strong just like young men, be young again. Old blind Indian see again and get young and have fine time. When Great Spirit comes this way, then all the Indians go to mountains, high up away from whites. Whites can’t hurt Indians then. Then while Indians way up high, big flood comes like water and all white people die, get drowned. After that, water go way and then nobody but Indians everywhere and game all kinds thick. Then medicine man tell Indians to send word to all Indians to keep up dancing and the good time will come. Indians who don’t dance, who don’t believe in this word, will grow little, just about a foot high, and stay that way. Some of them will be turned into wood and be burned in fire.

—

WOVOKA, THE PAIUTE MESSIAH