Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (49 page)

Growth happens when we seek to uplift the Other

The word dharma has often been translated as ethics, morality, righteousness and goodness. These English words are rooted in the notion of objectivity. But dharma is not an objective concept. It is a subjective concept based on gaze.

Depending on our varna, we will see dharma differently. For the shudra, it is doing what the master tells him to do. For the vaishya, it is doing what he feels is right. For the kshatriya, it is doing what he feels is right for all. For the brahman, it is realizing that everyone is right in his own way, but every one can be more right, by expanding his gaze. As our gaze expands, our varna changes and so does dharma.

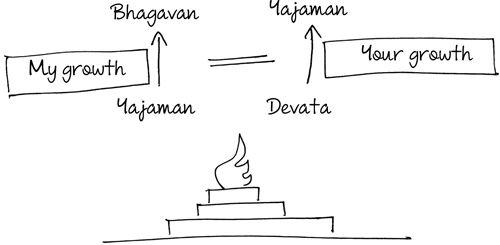

Dharma is about realizing our potential. While all other creatures grow at the cost of others (plants feed on minerals, animals feed on plants and other animals), humans can grow by helping others grow. This is not sacrifice. This is not selflessness. This is making the yajaman's growth an outcome of the devata's growth. This is best demonstrated in the ritual that takes place during Nanda Utsav.

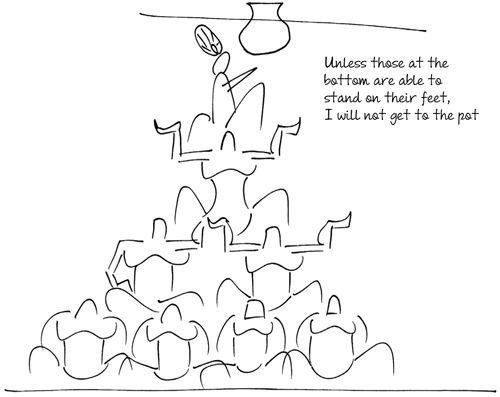

Every year, during the festival of Nanda Utsav, pots of butter are hung from great heights and human pyramids are formed to climb to the pot, commemorating how Krishna would steal butter from the milkmaids of Gokul and Vrindavan that was kept out of his reach when he was a child. In this exercise, the most crucial stage is the one in which people in the lowermost tier, who sit while the pyramid is being set up, have to stand up. Only when they stand, balancing the entire pyramid on their shoulders does Krishna get the butter. In their growth lies Krishna's success.

True expansion happens when I grow because you grow. When only I grow, it is selfish. When only you grow, it is selfless. Only plants and animals are allowed to be selfish, as they do not have the capacity to imagine, hence empathize. Only minerals and inanimate objects can be truly selfless.

In sanatan, only the digambar shramana, or the naked, wise sage can be truly selfless. Only he has no fear and can walk around without food, shelter or clothing, comfortable as he is. That is why monks were associated with forests, not social organizations, never allowed to stay or settle in a single place. Around Shiva, there are only snow-capped mountains where no life can thrive. It is good for the individual but not for those who are dependent on him.

For society, we need neither selfishness nor selflessness. We need a connection with the ecosystem. We need a method of mutual exchange and growth, one that includes more and more people. This is uddhar, the uplift of thought, which leads to an uplift in action, and intellectual and emotional growth, eventually leading to economic and political growth. The point is to invest in other people's growth such that the return is our growth. This is the path of Vishnu, the path of Shankar, the path of the Bodhisattva.

When Vikram took over as the CEO, he called the head of his human resource department and said he wanted to redesign job descriptions. He wanted financial goals to be the primary objective of executives. He wanted customer satisfaction and employee engagement to be the primary objective of junior managers. He wanted talent management to be the primary objective of senior managers. "As you climb the ladder, you cannot be paying attention to the same thing the same way," states Vikram.

Inclusion

It is easier to teach than to learn. It is easier to instruct than to let people be. It is easier to focus on things than thoughts. It is easier to expand our mind than get others to expand their mind. Wisdom is having the faith and patience to create an ecosystem where the mind-lotus can bloom at its own pace, on its own terms.

More yajamans are needed as an organization grows

At first, the yagna is small and simple. As the yagna progresses into a sattra and more fires are lit, specializations arise. Those who chant hymns and make offerings sit close to the fire. Those who protect the enclosure stand a little beyond. Those who get the firewood, mould the bricks, bake the pots, weave the cloth, tend to the cows and grow the crops, visit the enclosure only occasionally. Those who clean the enclosure are never seen as they emerge only when everyone has left.

Over time, those closest to the fire get the most attention and receive the most value while those who are further away and rarely seen, get the least attention and least value. This is because, often, though the yagna grows in size, the yajaman's gaze does not. This gives rise to the caste system where people are classified for the value placed on their measurable contribution (jati). Sanskriti becomes no different from prakriti where the dictum of survival of the fittest applies—the powerful thrive on resources and the less valued perish.

But humans are not animals. When Brahma at the top behaves like Gandhari, those at the bottom transform into Duryodhan, or even Ravan; at first subversive, but eventually defiant. When those at the top of the pyramid behave like devas and yakshas, those at the bottom will turn into asuras and rakshasas. Conflict rages. The sea rises. Pralay is imminent. All because Brahma was being stubborn and refused to see.

That is why in India the divine gaze is scattered and distributed through a variety of deities: gods who look after individuals (ishta-devata); gods who look after the household (griha-devata); gods who look after the village (gramadevata); gods who look after the city (nagar-devata); gods who look after the forest (vana-devata); and gods who look after communities (kula-devata).

These are not diminutive replicas of the distant bhagavan. Rather, each of these deities has an individual personality, a local flavour. The deities help in expanding and extending the gaze of the common bhagavan. Despite different roles, responsibilities and contributions, none of them feels inferior or superior; everyone feels revered.

Similarly, to create an organization where everyone feels they matter, it is important to extend the central gaze to the periphery, much like the hub-and-spoke model of supply chains which decentralized decision making so that every local market got attention from a local office, and did not rely on the gaze of the central office. However, this can only work when the head of the local office is as much of a deity in his or her own right and not subordinate to the deity in the central office.

Every deity takes ownership and acts locally keeping in mind global needs, sensitive to the internal organizational ecosystem as well as external market conditions. It is the yajaman's responsibility to create more Vishnus who know how to descend (avatarana) and to uplift (uddhar) those around them. Otherwise he will end up creating frightened sons of Brahma who think only of themselves and forget that a yagna is an exchange.

When he had only one office and thirty people serving clients, Sandeep could make everyone in his team feel included. Now that he's been promoted, he is a distant god; no one connects with him. They rarely see him except at the annual town-hall meetings where he speaks, but never listens. Sandeep's managers feel they are merely his handmaidens and his messengers, with no power or say in local matters. Naturally, the energy that once buzzed around Sandeep is restricted to the corporate office. In zonal, regional and local offices, there is just process, tasks and targets, very little proactivity or enthusiasm.

The yajaman has to turn devatas into yajamans

The sage Agastya performed tapasya and wanted to have nothing to do with society. But he was tormented all night by dreams of his ancestors who begged him to father a child. "Just as we gave you life, you have to give someone else life." This is Pitr-rin, one's debt to one's ancestors: one is not allowed to die unless one leaves behind a life on earth.

Thus every yajaman is obliged to create another yajaman to replace him. This makes talent creation an obligation. Talent management is not merely the passing on of knowledge and skills; it is the expanding of the gaze of the next generation of managers. It is the responsibility of those upstream to help those downstream see the world as they do.

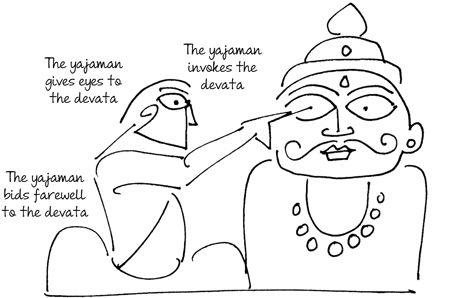

A new manager can be equated to the many images of gods and goddesses sold in the market; they are not worshipped until the ritual of prana-prathistha or the giving of life. This involves chakshu-daan, the granting of eyes, whereby the image becomes sentient and sensitive to the human condition, hence a deity. The yajaman thus gives eyes to the devata, helps the Other see what he can see. This is the essence of talent management.

A yajaman can be self-created, self-motivated, swayambhu. Or he may be created by another yajaman. Daksha sees talent development as an obligation and converts it into a process, a series of ritual steps. Indra sees talent management as a burden; he is even threatened by the talent. Vishnu sees talent management as an opportunity to help himself: for by helping someone else grow, we grow ourselves. By making another person dependable, the yajaman liberates himself from current responsibilities so that he can take on new responsibilities.

Raghu is a consultant in a large auditing firm. He has been made a manager with client-facing responsibilities. And he has been asked to attend a training programme designed to equip him to face the challenges of his new role. Raghu has been an executive for seven years; he does what he is told to do. Now they are instructing him to take initiative and ownership. Nice words, but how? And why? There is no discussion on that. At the end of the training programme he has been taught many skills on how to engage with clients, but there has been no change of gaze. He feels the only difference between his previous role and the current one is scale: now he has to do more of the same work for more clients through more people. He certainly does not see the world as the founding partner of the firm did. And he probably never will.

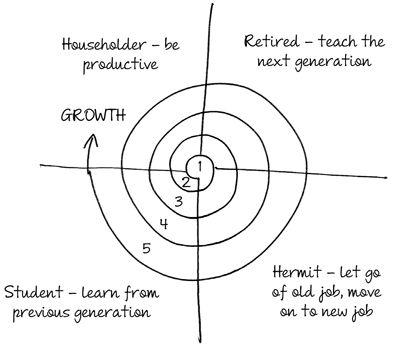

Creating talent enables us to grow

Vedic scriptures divide life into four phases: in the first phase we are students (brahmachari); in the second, we are householders (grihasthi); in the third, we retire (vanaprasthi); in the fourth, we renounce the world and retreat to the forest (sanyasi). The person who retires educates the student before he is allowed to renounce the world for the householder is too busy earning a livelihood for his family. Thus, while grihasthi is focused on wealth generation, the vanaprasthi and the brahmachari are involved in knowledge transmission.