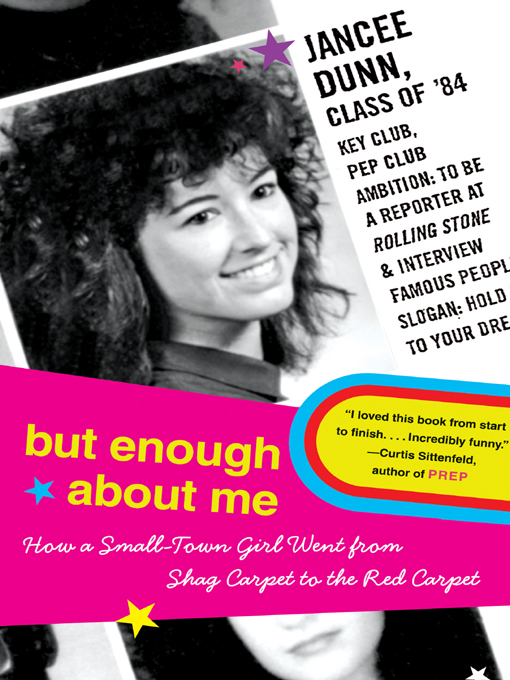

But Enough About Me

Read But Enough About Me Online

Authors: Jancee Dunn

HOW A SMALL-TOWN GIRL WENT FROM

SHAG CARPET TO THE RED CARPET

I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody too?

â

EMILY DICKINSON

I am fifteen. I am going to my first concertâ¦

My path toward interviewing the famous was a meandering one.

I gave up trying to escape my family long ago.

If you were to look at my past jobs, you'dâ¦

On the night before my job interview at Rolling Stone,â¦

The second I stepped through the doors of Rolling Stoneâ¦

The more I was exposed to the gloss of Newâ¦

What most people find festiveâa weekend at a beachâ¦

“Just hear me out,” my friend Tina was telling meâ¦

After a two-week period of flying to Los Angeles, London,â¦

I met Sean at an East Village roof party. Heâ¦

The next morning I called Dinah for the postmortem onâ¦

One morning at Rolling Stone, Jann called me into hisâ¦

The more it was apparent that my days as aâ¦

It was time that I started fixing my own affairs.â¦

I had just walked into my apartment with my nightlyâ¦

After my chat with Loretta I decided it was timeâ¦

As my life took a gentler turn, I started toâ¦

Saturday afternoon and my father was on the phone droningâ¦

Approach with caution. Often the band members have only recently arisen, even if it is well into the afternoon. Do not be cheerful. Avoid openers that sound parental, such as “Well! Looks like someone had a late night!” Have some breath mints handy, in case one of them has recently thrown up or has neglected to brush his teeth. Oral hygiene is not very “rock,” so be prepared.

As soon as the group is settled and their handlers have scurried to dispense energy drinks and aspirin, immediately name-check their tuba 'n' bass concept album that was released only in Germany, so that they know that you Get Them. Inevitably, however, your exhaustively researched questions will produce grunted, monosyllabic answers, for the band members will not want to seem like some eager teen pop group. Their goal is to make music, they will tell you pointedly, not to bone chicks or make videos or have their drinks paid for or stay in plush hotel rooms. Thus it is their duty to convey that these interviews are a nuisance, and they would be just as happy rehearsing in a garage somewhere. At this time you must roll out the heavy artillery.

Pay attention only to the drummer.

Laugh uproariously at his jokes. Stare with dumbfounded awe as he offers up his philosophies. Shake your head and say things like “I never thought about it before, but you

are absolutely rightâdrumming

is

a metaphor for life!” Listen, rapt, as he explains to you the genius of John Bonham's skinsmanship. As the puzzled but excited drummer blossoms under your admiring gaze, his other band mates, particularly the heretofore-mute sunglasses-wearing lead singer, will at first be confused, then annoyed. Finally, their competitive spirit will take over and they will enthusiastically jockey for attention, offering amusing anecdotes about groupies and telling off-color jokes.

Do not use any quotes from the drummer.

I am fifteen. I am going to my first concert unaccompanied by my parents. This is thrilling for a number of reasons. One, because I was invited by Cindy Patzau, the most glamorous girl in my sophomore class, still glinting with stardust after a recent performance during a school assembly in which she did a dramatic interpretive dance to Cyndi Lauper's “Time After Time.” She wore a clingy black bodysuit in front of the whole school. She was my hero.

“You want me to go with you?” I squeaked when she called. I sat with the popular kids in our high school cafeteria, but I certainly wasn't A-list. When I got my braces off that year, no one noticed for a week, whereas when Liz Kincaid had hers removed, there was much squealing and jubilation in the halls. During senior year I was voted Class Clown when I desperately wanted Best Legs (won by a girl with the movie-star moniker of Jill Shores). As the clown, I was the peripheral Don Rickles figure to the bronzed, carefree Dean Martins and Frank Sinatras, bristling with sour flop sweat, one bad joke away from being banished from the Sands. At the time of Cindy's call, I was on unsteady social ground due to a recent gaffe at a party. I was leaning against a wall, waiting in the bathroom line, when a senior named Mark, a hip soccer player who wore Adidas Sambas and liked the Clash, materialized behind me. He smirked. “Holding up the wall?” he asked.

Tell me, what is the sharp, snappy rejoinder to “Holding up the wall?” I gawped at him as everyone in the line nudged each other, waiting for my trademark lightning comeback. Holding up the wall. Holding up the wall. Seasons passed. The leaves on the trees outside withered, dropped, bloomed, and withered again. Holding. Wall. Mark abruptly turned away from me and started chatting up another girl. Good-bye, Rat Pack, hello, dinner theater in Jupiter, Florida.

“This show,” I said to Cindy. My words came out in a high-pitched, phlegmy squawk:

Zhis gghow.

I hurriedly cleared my throat. “Is it just you and me?” Surely there would be others.

“Yes,” Cindy said calmly. “I know you have good taste in music, so the ticket won't be wasted.” While I was processing this, I heard the click of a phone being picked up in my parents' bedroom. It was my younger sister Dinah. I could tell by her breathing. If I didn't play this phone call right, it could be my Waterloo, and I was frantic that Dinah shouldn't hear any bumbling. I needed to scare her. I inched toward the hallway in order to get a view of the bedrooms upstairs. Because there were three girls in our family, the phone cord in our kitchen had been stretched until it was ten yards long in our efforts to have a little privacy. Recently, my youngest sister, Heather, had managed to reach the hall closet, and conducted her preteen business with the door shut and key words muffled by the coats. I stretched the cord, gently but firmly, and crept over to where I could just glimpse Dinah in my parents' room. I waved furiously and her head jerked up.

Goddamn you,

I mouthed, affecting a tough squint. She froze like a snowshoe hareâout of fear, or stubbornness, I couldn't tellâbut she didn't hang up.

While I fought rising hysteria, Cindy detonated this: The concert was to take place at a college. We would have to cross the New Jersey state line to Haverford College in Pennsylvania. With her older sister! And we'd spend the night! In a dorm room!

“Cool,” I said, elaborately casual. “I'm in.” I could hear Dinah's sharp intake of breath. She knew as well as I that it would take a typhoon of tears to

persuade my strict father to let me go.

Hear me out, old man,

I thought grimly (he was thirty-nine at the time).

I am going. Oh yes. I am going.

A week later, after frenzied negotiations with my parents that rivaled the SALT talks in length and intensity, I was allowed to accompany Cindy to Haverford. The night before I left, after a bout of gastrointestinal distress at the thought of hanging around a VIP like Cindy for a sustained length of time (this would become a lifelong pattern), I retired to my room to pack.

Soon enough, there was a timid knock on the door. Dinah and Heather stood silently, knowing that they must be invited in. “Hey, can we watch you pack?” asked Dinah. At fifteen, I still held powerful sway over my younger sisters, and I carefully polished my mystique. Usually when they were allowed to enter the sanctum, it was so that I could extort their cash. My “garage sales” were a frequent scheme. “Garage sale in my room, five o'clock,” I would announce briskly as they raced to their rooms to scrounge for money or begged the folks for a forward on their allowance. Meanwhile, I rummaged through my drawers for tchotchkes to unload: a frayed collection of Wacky Pacs, a half-empty bottle of Enjoli, a trio of black rubber Madonna bracelets. As they waited by the door, twitching with eagerness, I would build momentum by popping my head out every once in a while with updates. “Five more minutes,” I'd bark. “Lotta good stuff in here, lotta good stuff. I really shouldn't be selling some of this.” Finally I would fling open the door and they would push over each other, running.

During one of these bazaars, my mother watched from the doorway, arms folded, lips pursed. “You should be ashamed of yourself,” she said.

“Why?” I asked coolly, shutting the door on her. “For bringing color and excitement into my sisters' lives?”

I also gave various lessons. Ballet instruction cost fifty cents, seventy-five cents for the deluxe. For that particular con, I recited instructions into a tape recorder (“Point your toe forward, and back; repeat”). When my two customers arrived, I pressed “play” and walked out, only feeling a twinge later when Heather said, “I wish you hadn't left. We were so disappointed because we wanted to be with you.”

Another proven revenue stream was music-appreciation seminars. “Now, do you two remember who this is?” I'd say, carefully putting

Crimes of Passion

on the record player as they sat cross-legged on the floor.

Heather frowned. “Blondie?” she ventured.

“Pat Benatar,” I'd say crisply, pacing back and forth. “This is called âTreat Me Right.' Pat's from Long Island. She used to be a waitress. She is going out with her guitarist, Neil Giraldo. Got it? Dinah, are you taking notes?”

This was one of the few times I was not interested in their cash. Still, I drew out the moment by continuing to pack as they waited on the other side of the door. “We've got cookies,” Heather called. “I just made them. Sugar cookies.” Taken from an old recipe in an ancient

Better Homes and Gardens

cookbook, sugar cookies were a family staple, blindingly white thanks to Crisco, white flour, and cups and cups of sugar. Eagerly, I opened the door. They bounded over to my bed and we all flopped onto it, shoveling warm cookies into our mouths. Then, after our sugar high spiked, I got down to business, imperious once more. “I need to pick out an outfit for the show,” I said, rising from the bed and opening my closet doors. What they would never guess is that as my back was turned to them, I was thinking,

I wish that it could always, always be just like this, with you two giggling and jostling each other on the bed next to my elderly, snoozing cat. Must I leave? Must you leave? Can't we stay?

“You look good in everything,” said Heather loyally as I held up a pair of elasticized aqua paisley In Wear pants. Heather was five years younger than I, so she was an easy sell. Two years separated Dinah and me, so her compliments were less effusive.

“What about pajamas?” I fretted. I couldn't wear my pink flannel Lanz nightgown to a college.

“Wear your good sweatpants,” Dinah counseled. Only in New Jersey could you have “formal” sweatpants. “And if you promise to take care of it, I'll give you my Hard Rock London T-shirt.”

“Slippers?” I said.

She shook her head. “No. Socks, but not dark ones. Peds would be best.”

“What if some college guy tries to hit on you?” asked Heather gleefully, bouncing on the bed.

That was not going to happen, particularly since I had recently gotten a perm that was extreme even by mideighties New Jersey standards, rendering my hair as dense and impenetrable as a boxwood hedge. But of course, I couldn't tell them that.

“I'll do what I usually do,” I said. There was no “usual.” “I'll say I have a boyfriend.”

After I shooed my sisters out of my room, I sat at my desk and wrote out a list of potential topics to bring up with Cindy in case there was dead space.

- Do you think Mr. Boone looks better without his mustache?

- What's your take on scrunch socks?

- Do you watch

All My Children

? If so:- a. Do you think Jenny and Greg make a good couple? If not, why not?

- b. Do you want to come over to my house during the big episode when Jenny and Greg get married? You can't? Oh, you have field hockey practice? No, right, it was a bad idea anyway.

- a. Do you think Jenny and Greg make a good couple? If not, why not?

The next day, exhausted after a nerve-jangling ride to Pennsylvania (“Do you know,” I said to Cindy in one of my many conversational misfires after I had run through the list, “that you're a dead ringer for that actress Hedy Lamarr?”), we finally lined up in front of the concert hall. Slowly I came to life. My first show! The college kids around us all looked impossibly poised. How do they know where to buy clove cigarettes? Did they do those asymmetrical hairdos themselves, or did they go to a salon? After an eternity, we made it through the door. I took a deep breath, tasting the gloriously stale, loamy, cigarette-tinged air.

“Let's try to get up close,” Cindy said. I was afraid of crowds but I had to impress her, so I charged recklessly through the audience so we could secure a position near the front. Guitar techs in scraggly ponytails, shorts, and tube socks darted around the stage, adjusting equipment. The crowd began to cheer. Then: Out went the lights. My pulse surged crazily.

I could do this every night,

I thought, ping-ponging with excitement.

Every night of my life.

And then, a spotlight came on, the band bounded onstage, and an announcer hollered those life-changing words: “

Folks! Please give it up! For! THE HOOTERS!

”