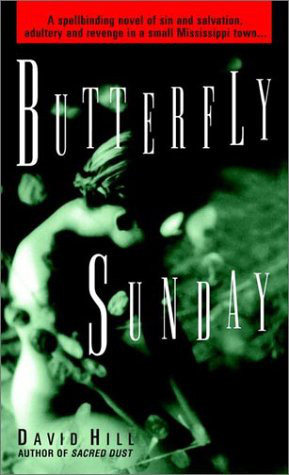

Butterfly Sunday

Authors: David Hill

Tags: #Psychological, #Mississippi, #Man-Woman Relationships, #Adultery, #Family, #Juvenile Fiction, #Political, #General, #Literary, #Suspense, #Clergy, #Female friendship, #Parents, #Fiction, #Women murderers

PRAISE FOR

BUTTERFLY SUNDAY

“A moody, twisted story of lust, love, revenge, and religion … Hill is a truly impressive talent, a master of character and atmosphere. And he weaves a complicated plot, full of flashbacks that layer past and present.…

Butterfly Sunday

left me wanting to read more by Hill, and soon.”

Butterfly Sunday

left me wanting to read more by Hill, and soon.”

—

Boston Sunday Globe

Boston Sunday Globe

“Richly textured … elegantly constructed … [Hill] deftly employs time shifts and a style at once spare and lurid, to unfold this gothic tale.… A gorgeous crazy quilt of a novel, filled with saints and sinners bent on mayhem, southern-style.”

—Kirkus Reviews

(starred review)

(starred review)

“Perceptive, rich writing.”

—

The Baltimore Sun

The Baltimore Sun

“The strengths are undeniable and impressive.… Hill has created some powerful imagery, some memorable characters and an atmospheric setting that will captivate lovers of romantic suspense.”

—

Publishers Weekly

Publishers Weekly

“There is no better storyteller than David Hill. There is no better book than

Butterfly Sunday.

In his dazzling illumination of things unseen and things unimagined, David Hill has created an unforgettable cast of characters and an enormously satisfying read.

Butterfly Sunday

is a major miracle.”

Butterfly Sunday.

In his dazzling illumination of things unseen and things unimagined, David Hill has created an unforgettable cast of characters and an enormously satisfying read.

Butterfly Sunday

is a major miracle.”

—Shirlee Taylor Haizlip, author of

The Sweeter the Juice

The Sweeter the Juice

“Butterfly Sunday

has as many twists and turns as a mountain road and may be the best blend of sex and religion since Elvis.”

has as many twists and turns as a mountain road and may be the best blend of sex and religion since Elvis.”

—

St. Petersburg Times

St. Petersburg Times

Also by David Hill

SACRED DUST

A Dell Book

Published by

Dell Publishing

a division of

Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

This a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2000 by David Hill

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

Dell ® is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc., and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76721-9

Published simultaneously in Canada

September 2001

v3.1

In Memoriam

Robert S. Hill Sr.

January 31, 1919–October 30, 1997

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to many, who include:

Lisa Bankoff, Danielle Perez, Wanda Wilson, Michael Cherry, Ann Hughes, Betty Hill, Lea Queener, Martha Holifield, Joey Miller, Bill Wilson, Gary and Rhonda Brown, John Michael Ellis, Brenda Miao, John Pielmeier, Mary Gallagher, Lonnie Hill, Libby Boone, Kate Permenter, Glenn Anderson, and many, many more.…

“Henceforth I learn that to obey is best

,

,

And love with fear the only God, to walk

As in his presence, ever to observe

His providence and on him sole depend

,

,

Merciful over all his works, with good

Still overcoming evil, and by small

Accomplishing great things …”

John Milton

Paradise Lost,

Book XII

Book XII

1

EASTER SUNDAY, APRIL 23, 2000

3:12P.M.

The state would execute her. She knew that. She accepted it the same way she had accepted the fact that there were too many needlepoint pillows in her living room. Someone would stick a needle in her arm and she’d swoon. Her eyes would roll back into her head and she’d transform from a person into a thing. They’d kill her, but not her meaning. They’d get a full confession, but never a word of remorse.

She had so many of her mother’s pretty things around the house. It sickened her to think Audena would clean out the place. Her sister-in-law wouldn’t know what to keep and what to pitch. Audena would probably keep the rag rugs and use Mama’s Aubusson in the doghouse. Well, so what? Without past associations, heirlooms reverted back into things. She slipped two large

photographs out of their ornate sterling silver frames: her parents’ wedding in ’49 with Daddy in his Navy uniform, and her brother Henson’s fourteenth birthday at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. Those she would keep to the end.

photographs out of their ornate sterling silver frames: her parents’ wedding in ’49 with Daddy in his Navy uniform, and her brother Henson’s fourteenth birthday at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. Those she would keep to the end.

She had to think about her immediate future, what to say, what to hold in silence. What to expect from the police and the legal system. There would be questions, of course, followed by her detailed confession. Then they’d charge her with murder. She’d spend her first night ever in the county jail. A public defender would turn up. There’d be an arraignment. Then she’d have to stand her ground. She’d enter a guilty plea, provided she was allowed to detail not only her crime but also a history of her relationship with her victim.

The world would know and remember everything.

When the deputy knocked, she’d open the door, hand him her overnight bag, and say, “What took you so long?”

Her eyes followed a garland of pastel roses in the carpet to a printed rectangle of lavender paper on the floor at the far end of the sofa. It was this morning’s church bulletin. The front was a rough pencil drawing of a myopic Jesus wearing a crown of thorns—Averill’s crude handiwork. His insistence on demonstrating his complete lack of artistic talent every week only made sense if you accepted the fact that he had never made a lick of sense. As usual, he’d goaded her into lettering the title of his sermon with her calligraphy pen.

Why did Jesus go to Jerusalem?

It was one of his standby sermons. In her year and a half as his wife, she’d already heard it twice. She had always tuned it out as more of his sanctimonious nonsense. However, now, tracing the carefully drawn letters

with her finger—right now, listening in the quiet aftermath for the sound of an approaching car—she saw the meaning in the question. Why had the cross-eyed fool ridden that swayback mule into downtown Jerusalem in broad daylight? Why had he placed himself in the eager hands of his executioners? Why hadn’t he turned off that doomed highway and slipped into the anonymous sanctity of life under an alias?

with her finger—right now, listening in the quiet aftermath for the sound of an approaching car—she saw the meaning in the question. Why had the cross-eyed fool ridden that swayback mule into downtown Jerusalem in broad daylight? Why had he placed himself in the eager hands of his executioners? Why hadn’t he turned off that doomed highway and slipped into the anonymous sanctity of life under an alias?

Would millions have considered what he had to say for the next twenty centuries if he had? No. He saw the limited value of his existence next to that.

Leona had no desire to start a religion, but she knew that her willingness to die for the opportunity to tell everything would inflate the value of her every word.

She was half-crazy with running to the front porch every time a green persimmon fell on the roof. She could just picture his amorphous specter floating up the road from the church. That was nothing but guilt. Guilt—that pernicious misery. It liked to give her a sick headache. Except of course she’d already had one longer than she could even remember. She was a first-class mess. One twit of a sparrow’s tail was all it took to convince her that the dead could walk.

Not that she doubted the existence of ghosts. The past—and to her that meant the dead—had ruled her life for several years now. But that was the spirit world; apparitions and images conjured from memory. This all-encompassing terror that she could neither respect nor elude was the impossible idea of dead flesh come back to life.

She kept hearing a nonexistent car on the road.

This wasn’t that saccharine, pseudo-remorse that people used to hide their immoralities. She wasn’t “feeling guilty,” the way people will when they’ve done something

they wish they hadn’t. Certainly, she had regrets around it. Killing him was all bother. She would have much preferred some magic ability to undo the things he’d done. However, that wasn’t possible. So, the irksome business had fallen to her. She wasn’t a natural killer. The instinct had been raised out of her. She had pondered her way to the brink of it a thousand times, and then turned gutless or moral, depending on your perspective. She figured she must not have had any perspective left—or she would have never pulled it off.

they wish they hadn’t. Certainly, she had regrets around it. Killing him was all bother. She would have much preferred some magic ability to undo the things he’d done. However, that wasn’t possible. So, the irksome business had fallen to her. She wasn’t a natural killer. The instinct had been raised out of her. She had pondered her way to the brink of it a thousand times, and then turned gutless or moral, depending on your perspective. She figured she must not have had any perspective left—or she would have never pulled it off.

That was giving the situation a wide berth, though. She didn’t feel any lack of judgment here. She wasn’t suffering any remorse or shame. It seemed very sane and satisfactory to Leona—a good job very well done. So guilt, she was learning this afternoon, had nothing to do with regret. Guilt was contemplation of the inescapable consequences. Guilt was not getting away with it.

Other books

Walking on Sunshine by LuAnn McLane

Done Being Friends by Grace, Trisha

At Last by Stone, Ella

Kastori Tribulations (The Kastori Chronicles Book 3) by Stephen Allan

The Good Doctor by Karen Rose Smith

Uncharted Stars by Andre Norton

Eliza’s Daughter by Joan Aiken

Bin Laden's Woman by Gustavo Homsi

Tidewater Inn by Colleen Coble

The Story Traveller by Judy Stubley