Calcutta

Authors: Geoffrey Moorhouse

GEOFFREY MOORHOUSE

To the men of the CMPO who are

incorruptibly

there and to E. P. RICHARDS, sometime Chief Engineer of the Calcutta Improvement Trust, who restored some of my national pride

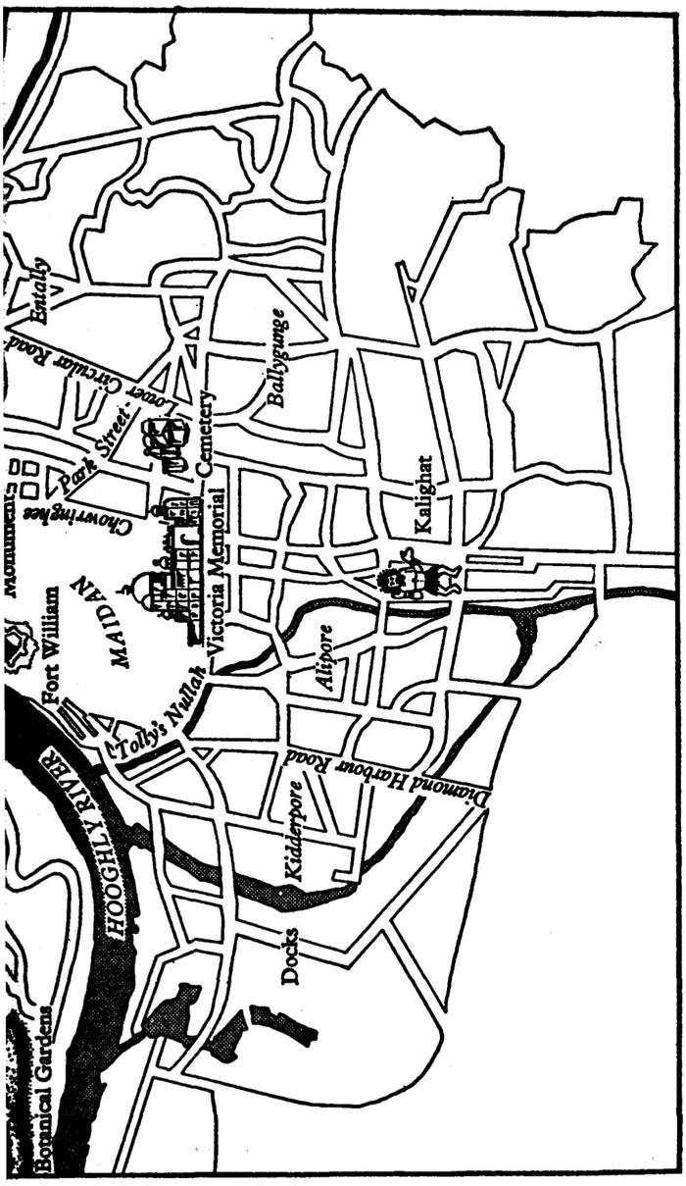

1. Calcutta 1971 – A crossing along Chowringhee (

Keystone Press)

3. Rabindranath Tagore (

Camera Press; Photo: R. J. Chinwalla

)

4. Jyoti Basu (

Camera Press; Photo: Sunil Dutt)

5. The Tollygunge Club (

Photo: Mark Edwards

)

6. Ochterlony Monument, on the edge of the Maidan (

Photo: Mark Edwards

)

7. A few of the homeless, asleep outside the Great Eastern Hotel (

Photo: Mark Edwards

)

8. A slum of makeshift shanties by a suburban railway line (

Photo: Mark Edwards

)

9. Bathing and washing clothes at the side of the road (

Picture-point

)

10. Park Street Cemetery (

Photo: Geoffrey Moorhouse

)

11. The ultimate poverty – the Hooghly as a grave (

Photo: Mark Edwards

)

12. The voice – and the mood – of Calcutta in 1971 (

Photo: Mark Edwards

)

The author and publishers are grateful to the copyright owners for permission to reproduce the pictures.

A GREAT

deal of this book is the product of my own observations in Calcutta. I hope the extent of this will be obvious from a

comparison

of the text with the source notes at the end. I spent a couple of months there on two visits in 1969 and 1970 and many people helped me while I was in the city. I would certainly have been lost without the guidance and friendship of Prasun

Majumdar

, who shared a great deal with me, including one of my two gheraos. I would have missed a great deal without the kindness and help of Professor and Mrs Arthur Row Jr and their family. I was also much assisted by Inder Malhotra, Ragau Banerjee, Niranjan Sen, Mr and Mrs S. Sircar, Mr and Mrs D. L.

Bannister

, Lindsay Emmerson, Tim Scott and Ken MacPherson. My thanks to all of them, as well as to Mr D. R. Kalia and his staff at the National Library, who were extremely helpful during my researches among their bookwormed records. I am similarly indebted to Mr S. C. Sutton and his assistants at the India Office Library in London, on whom I relied heavily for much of the documentation in this book; and I’d like to salute Mr D. W. King of the War Office Library, who dug out a paper on the origins of the Dum Dum bullet. My thanks, too, to my old colleague Peter Preston, who twice smoothed my passage to India. My biggest debt, however, is to John Rosselli, student of Bentinck and Bengal, who presented me with the idea of this book. Without him it would not have been written. I hope it doesn’t disappoint him.

It would be as well to say something here about my spelling of local names. There is absolutely no consistency, I’m afraid, either in Calcutta or in this book. When Jamshedpur is spelt with a final ‘pur’ the same ought to go for one of Calcutta’s main thoroughfares, but here it is rendered as Chitpore Road; I apologize in advance to any readers who are accustomed to the other version and I can only plead that the one I have used seemed to be the most popular in the city. People who know Calcutta and India better than I do will probably find other examples of a similar kind. Where possible I have used the local telephone directory as arbiter of style; otherwise I have simply tried to be clear. I have thus failed to call Benares by its now customary title of Varanasi and I hope my Indian friends will forgive me this wilful howler; but I have dared to call the River Ganges by its proper name of Ganga on the assumption that even foreigners can absorb the translation without being

confused

. If anyone needs convincing further of the difficulty in accurate spelling of proper names, it is worth remarking that in September 1969, one of Calcutta’s chief newspapers was

publicly

asking whether the Ochterlony Monument must now be rendered as Sahid Minar, Saheed Minar or Shaheed Minar.

This is perhaps the place to say to anyone who may still be in doubt that Calcutta has nothing at all to do with the revue that bears its name. According to Kenneth Tynan, whose brainchild that was, ‘

Oh!

Calcutta!

’ is the title of a painting by an elderly French surrealist named Clovis Trouille. It is a pun on the French Oh! Quel Cul T’as, meaning ‘Oh what an arse you have’. The reference is to the fact that the model in the picture is displaying her bottom to the painter. I’m obliged to him for that information.

I CAN

offer no bigger or better excuse for writing a book about Calcutta than something on the lines of the old Mallory

quotation

about Everest; it is there. It is strange, though, that no one has attempted anything like a portrait of the city since Montague Massey published his recollections in 1918. Since then there has been an excellent but highly technical social survey by N. K. Bose and two or three books on Bengali politics, all written by scholars for other scholars; nothing else except occasional memoirs with fleeting references. Yet this was the second city in the British Empire and, for what the computation is worth, it remains the second city of the Commonwealth. It is also the fourth city in the world. Our failure to take much notice of it maybe tells us more about ourselves than it has not told us about Calcutta.

In a sense, the story of Calcutta is the story of India and the story of the so-called Third World in miniature. It is the story of how and why Empire was created and what happened when Empire finished. It is the story of people turning violently to Communism for salvation. It is also the story of Industrial

Revolution

. The imperial residue of Calcutta, a generation after Empire ended, is both a monstrous and a marvellous city.

Journalism

and television have given us a rough idea of the

monstrosities

but none at all of the marvels. I can only hope to define the first more clearly and to persuade anyone interested that the second is to be found there too.

A hazard facing any writer who attempts to bring history up to date – as I did in the last few pages of this book a dozen years ago – is that events shortly afterwards may make his perspective and his conclusions seem comically inappropriate. It may

already

be thought that the apocalyptic vision with which I finished

Calcutta

fell rather heavily into this trap for the unwary author; and I shall be very happy if someone in the next century is able to confirm that this was indeed the case. Certainly no cataclysmic plague has visited the city since I first studied it, nor have the pavement poor risen with ferocity to dispose of the rich in angry bloodshed. Yet I would not wish to change a word that I wrote then. I was expressing as best I could what Calcutta made me feel. Those paragraphs were much less prophecy than speculation. Above all, they were my effort to convey a Spirit that seemed to be abroad in a dark night of the city’s soul.

In fact, there was a moment soon after the book was published when it seemed that my imaginings might be given dreadful substance. In 1971 there occurred the revolt in what was then East Pakistan against Yahya Khan’s military government in Islamabad, which led to the establishment of Bangladesh.

Inevitably

this produced, as every other terrible conflict on the

subcontinent

has always done, uncountable masses of refugees streaming away from the centre of violence. With Calcutta only a short distance from the border, the majority of them headed for the city, whose outskirts were soon swollen by many encampments of what the international jargon refers to

abstractly

(and I abstractedly) as ‘displaced persons’. Multitudes, who would have starved to death without the charity of the Indian government and the aid that came from further afield, lived for a long time in great drainpipes, which were lying in readiness for some half-executed municipal enterprise, and in a new spread of shanty towns. In those first few months after their arrival, until Calcutta had yet again adapted itself enough to demonstrate its resilience in the face of difficult odds, the already overloaded city must have been perilously close to breakdown, urban collapse or whatever we choose to call the ultimate metropolitan nightmare. After a couple of years, by which time even Islamabad had been forced to recognize the independence of Dacca, many of the refugees staggered back whence they had come; but some stayed behind to compound, as refugees always do, Calcutta’s everlasting problems.