Cambridgeshire Murders (18 page)

The chopper had been discovered on the day after the murder in the cupboard under the scullery sink. It had had a damp patch on it. The back of the chopper exactly fitted the large wound on Miss Lawn's forehead. Although Roderick had given his estimate of the time of death the coroner was keen to call other witnesses to help to establish a more precise time.

A baker named Albert Ding was making deliveries and one of his drops was to Miss Lawn. He had left the bakery at 10.20 a.m. and estimated that he would have been at the shop by 11.45 a.m. She had ordered a dozen 2lb loaves and paid him 6s with money from the till. He had delivered to her on numerous other occasions and knew that if she had needed to pay him a larger amount she would have gone into the back kitchen where she obviously kept more cash.

Another witness to confirm when Miss Lawn had still been alive was Mrs Ada Webb who had sent her two daughters to the shop with half a crown to buy soap and blue. The girls had left her at 11 a.m. and returned twenty minutes later with the items. The elder of Webb's daughters, Elizabeth, had said that they had been the only customers in the shop.

At 11.05 a.m. a telephonist named Arthur Sexton went to the shop to buy cigarettes and found the shop door locked. He timed his visit by the passing of the Newmarket Road bus. Although the timing of the Webb girls' visit was also approximate, they must have missed each other by only a short time.

Rose Rolph gave the next evidence. At 11.30 a.m. she cut through Milton Walk when she noticed a small sound: âI heard a little muffled noise of some description â a sort of dull noise. I thought it was a child crying. It was a quiet noise.' She admitted that she was not sure that the noise was being made by a person but was nevertheless drawn to the sound. This evidence tied in with the account a 13-year-old named Jack Cornwell gave to the police. He had seen someone go through Miss Lawn's back gate at some time between eleven and twelve o'clock and had run to the gate hoping to ask for the return of a ball that he had lost in the garden a few days earlier. By the time he had reached the gate it was re-locked.

Miss Lawn's best friend, Elizabeth Papworth, described her as someone who would talk freely to customers but be guarded in relation to her private affairs. She was shown the chopper but was unable to identify it. Other witnesses who knew Alice Lawn well were also unable to recognise it, but the police eventually found proof that it was the same or similar to one Miss Lawn had kept on a table next to her scullery. The inquest was then adjourned leaving the police to ponder two possible leads.

Firstly, a young man named Leonard Marshall, an under gardener on Christ's Piece, had seen a man standing near the shop. It was between 2.30 and 3 o'clock and Leonard thought he would ask the correct time. As he approached the man he realised that he was counting some coins and decided not to interrupt him. He described the man as well dressed, wearing a light grey suit with a trilby hat. The man was of Jewish appearance and biggish built with a dark complexion. Leonard recognised the man as someone he had seen before but only on market days.

Secondly, and in seeming contrast to her private nature and her brother's observation that âshe was always nervous of any man', it transpired that she had had a lodger. The man was called Mr Grundy and had lived at the house for almost two years. He, however, had left two years previously. He had been a clerk at the Correspondence College and had suffered a mental breakdown, leaving 70 King Street after being admitted to the Fulbourn asylum. He had since been discharged from there and, as far has anyone was aware, had had no further contact with Miss Lawn.

While the second line of enquiry proved to be a dead end, Leonard's sighting of a man with a dark complexion gave the public something to focus on.

The inquest re-opened at 10.30 a.m. on Friday 19 August. The following Wednesday's edition of the weekly paper,

The Cambridge Chronicle

, blared the headlines âW

ILFUL

M

URDER

!' and âG

UARDED MAN IN

C

OURT

'. The paper gave not only the verdict of the inquest, but also the details of the arrest and committal of the new name in the case: Thomas Clanwaring.

Clanwaring was 23 and claimed that he had come to Cambridge to look for work as a French polisher. In fact Clanwaring was in such a habit of inventing stories that it soon became evident that it was almost impossible to tell when he was telling the truth and when he was just amusing himself or seeking attention.

He made several statements to the police, and in the first of these he claimed the following:

My home address is 66 New Street, Silvertown. I was born at Bethnal Green, then moved to Silvertown and have lived there ever since. I came from Baldock to Cambridge on Friday night. I have been in the town just over a week. I stayed at the Black Bull, Baldock; was there for four days. I came from Manchester to there. I had come through Manchester; I walked from Manchester to Baldock. I did not sleep a night in Manchester. From Manchester to Baldock is, I think, about 400 miles. I slept at nights under stacks. I have been from Silvertown over 31/2 years. During that time I have been working for chaps on the road, shovelling up and sweeping. I came to Cambridge trying to get work as a French polisher. I tried for work at Leavis' and other places. I have only been with two chaps on two occasions since I have been in this town. Twice I have been with the two, making three persons, otherwise I have always been by myself. I can show you where one lives. Once when I was with them, the two chaps and I went into a public house in this road where it said Under New Management. I don't know where I was on Wednesday. I know where I was on Saturday; I was in the town selling postcards.

The two chaps he referred to were Albert Briggs and Frank Turner who were also out of work labourers. This part of his statement was reasonably accurate, but virtually nothing else was; Clanwaring had been in Bedford gaol until 16 July when he had been released with the sum of 7

s

6

d

. He had been in prison charged with the theft of five bicycles.

He had been in Bedford for five days but had no luck finding work and soon his money had run out. He went to Baldock and pretended to be deaf and dumb for three days, then went to Letchworth Baths and proclaimed: âOh God! Ain't it rotten.' He then told anyone who would listen that he had miraculously recovered his speech after 41/2 years. He took this story to the

Daily Sketch

and hoped he would get paid for it. Part of this story was that he had originally lost his speech and hearing after the Silvertown explosion

3

and therefore gave his address as 66 New Street, Silvertown. It transpired that this was an address he had invented and he really had no home in England. When questioned in court he denied telling people he was Jewish and said, âI don't know whether I am a Hottentot;

4

my mother was a North American and my father a South African'. When Clanwaring arrived in Cambridge he carried on telling the same deaf and dumb story and, even on the morning of Alice Lawn's murder, had been attempting to con

The Cambridge Chronicle

with it.

Clanwaring made a long statement at the inquest and was followed by Inspector Mercer who gave a detailed account of all the various and inconsistent statements that Clanwaring had made since his arrest. Other witnesses were called, many establishing the probable time of Miss Lawn's death and others pinpointing Clanwaring at various locations throughout the Wednesday of the murder.

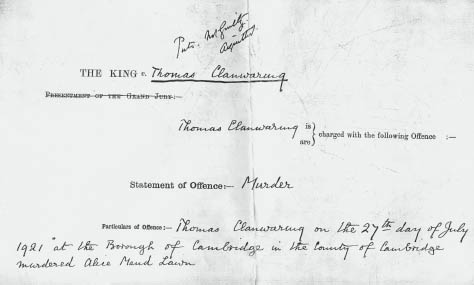

Clanwarings Statement of Offence document from the Assizes

. (Authors Collection)

The coroner warned that, of the total evidence given, only a proportion could be relied upon at a trial and that the case against Clanwaring was circumstantial. The inquest jury retired for twenty minutes and returned the verdict that they were unanimously agreed that Alice Lawn had met her death by wilful murder and that they were convinced that Thomas Clanwaring was guilty of the crime. Clanwaring was therefore committed for trial at the next assizes and held at Bedford gaol.

The trial opened on 17 October 1921 before Justice Bailhache. H.O. Carter, a London lawyer hired by a woman described only as âa wealthy North Country lady', defended Clanwaring. She had felt moved by Clanwaring's predicament and was keen to ensure that he had the chance of a fair trial.

Full details of the crime were presented including details of Miss Lawn's financial circumstances. Based on the transactions that Miss Lawn had made during the morning of 27 July the police knew that at least a 10

s

note, a shilling and half a crown had been removed from the till. During the search of her house £130 had been found in notes under her carpets and lino and under her piano. In the attic they found a tin containing £13 10

s

in notes, £4 in silver and an old purse containing £21 in gold. There was also a post office savings book showing a balance of £469 9

s

9

d

, making her a secretly wealthy woman. Not even her closest friend, Elizabeth Papworth and her family, knew anything about her money.

Curtis Bennett K.C. and Travers Humphreys represented the case for the Crown. The prosecution intended to call in excess of forty witnesses: they aimed to establish that it was physically possible for Thomas Clanwaring to have been at Miss Lawn's shop at the time of her death and that robbery could have been a motive. They also sought to show that Clanwaring had behaved suspiciously after Miss Lawn's death, that he had implicated himself in the murder by comments he had made, and had, according to two fellow Bedford gaol prisoners, confessed to the crime.

With this in mind Bennett showed that on the day of the murder Clanwaring had been to the mayor at 10 a.m. to obtain a pedlar's licence. At between 10.20 and 10.30 he had spoken to two women in King Street. They had stood almost opposite Miss Lawn's shop as Clanwaring had told them that he needed 25

s

to get photographs taken. Shortly after this he met up with Briggs and Turner, visited two local businesses and by 10.55 a.m. had entered the Rose and Crown public house in Newmarket Road where he stopped long enough to have a drink. While he was in the pub he attempted to sell a wristwatch for 4

s

and had apparently said: âI would not sell this for 4

s

, but I'm absolutely on the rocks.' The previous evening he had also attempted to sell his cap for 1s.

Witnesses reported that he had left the pub again just before eleven. In theory he had just about enough time to have reach King Street and lock himself inside the shop before Arthur Sexton found the door locked at about five past. Clanwaring was next sighted between 11.30 and noon near 70 King Street and the Wednesday market. At 12 o'clock he entered Warrington's butcher's shop in Magdalene Street where he exchanged 10

s

of coppers and silver and a 10

s

note for a £1 note.

Next, at about 1 p.m., he went to Briggs' house and asked to swap coats. Clanwaring said he wanted to be smart for a trip to the cinema and paid Briggs 1s for the exchange. When his original coat was later examined it was stained with paint but no blood. According to the police surgeon the lack of blood did not prove Clanwaring's innocence, as the killer could have remained blood free.

At 1.30 p.m. Clanwaring returned to his lodgings, which were almost a mile from 70 King Street. He left immediately and returned between 3.20 and 3.30. By the time he came back he had purchased a stock of postcards and told his landlady that an old woman had been murdered. Miss Lawn's body had been discovered at 3.15 and the police informed at 3.25: the prosecution argued that Clanwaring had somehow heard of the murder before everybody else in Cambridge.

A number of blue Lloyds Bank bags had been found in Miss Lawn's shop and an identical one had been found in Clanwaring's possession. Firstly Clanwaring had claimed that he had found it in the street, then changed his story to say that he had taken it from the owner of a street organ when they had both been at the Racehorse pub.

How Clanwaring had gone from being penniless at just before eleven to having over a pound by lunchtime was a mystery. The coincidence of the bank bag, the change of clothes and his presence in King Street were all against him.

In addition Clanwaring was in the habit of talking to anyone prepared to listen to him and once in custody had made comments to fellow prisoners, Glenister, Bingham and Clark, that were described as âtantamount to a confession'. On 6 August Clanwaring had said: âI'm for it', and put his hands around his throat. âFor a watch?' Glenister asked. Clanwaring had answered: âNo, Lawn's job at Cambridge.'

On 20 August Clark testified that Clanwaring had told him: âI shall get hung for this, but I have got the âtecs set, as there was nobody else there but me.'

Commenting on his conversation with Clark, Clanwaring said that he had not meant to imply that he had âdone it' but simply that he would hang if he were found guilty. But all Clanwaring's denials and claims were met with scepticism and even his own defence described him as âThe biggest liar I have ever met'.