Cambridgeshire Murders (9 page)

Tilbrook also confirmed that the stomach, intestines and earth had been delivered to Professor Taylor, the next witness to take the stand. An analysis of the contents revealed that the intestines were very well preserved, but both the insides and outsides were extremely inflamed, with inflammation of the oesophagus and the stomach, which was distended and contained about ten ounces of fluid. Apart from this inflammation however, there were no signs of general disease and the professor said that this was consistent with the ingestion of an irritant poison. He found black particles in the stomach lining but no food and just a small amount of digested matter in the intestines giving him the impression that violent purging or vomiting had occurred. The stomach contents comprised mucous fluid, water and arsenic amounting to two grains with further arsenic embedded in the stomach walls. He summed up his findings, saying:

I am prepared to say that death was produced by arsenic administered to the deceased in large quantities. The symptoms are vomiting, thirst, and purging and finally collapse. The recipient of arsenic generally feels at once as if struck with death. I am clearly of the opinion that the deceased died from arsenic and no other cause.

Professor Taylor was asked to examine the parcel found in Lucas's pantry. He took a small sample for testing and applied Reinch's test, which is a common test for the detection of arsenic and produces crystals. When he returned to the stand he stated that, âit is undoubtedly metallic arsenic, uncombined with anything. I have produced the clearest crystal.'

Mr Cross, called in to confirm that he had given the arsenic to Lucas, explained that it had been nearly a pound of arsenic and recalled âthis is the parcel I gave him. I gave it to him in the lime house in the condition in which this is. He took it away. It was a week after Old Michaelmas Day

3

I gave it him.'

Before leaving the stand he was cautioned by the judge: âFor the future I would advise you to take care how you deal with so dangerous an article as that before you. You should have seen it destroyed yourself, and I would caution you against the possession of so large a quantity,' to which Mr Cross responded that Elias Lucas had worked for him for four years and had never given him reason to think he could not trust him.

While the cause of death and the availability of arsenic were vital to the defence's case it was undoubtedly the human element that fascinated the public, and plenty of witnesses came forward with fascinating insights into the life and death of Susan Lucas.

Henry Reeder testified that his daughter Susan had persuaded him that since his wife had died Mary would be better off living with her. Reeder was in the unenviable position of giving evidence that could incriminate one of his daughters at a trial intended to bring to justice the killer or killers of the other daughter. Perhaps it was this conflict of interests that led him to speak so openly about Susan's personality. He claimed that she had had a violent temper and had often said that she would destroy herself by drowning. When cross-examined, however, he admitted that these suicidal outbursts had occurred before her marriage and that he had never heard her repeat these threats since. Elias Lucas also referred to Susan's suicidal tendencies, but said that he had dismissed the idea that his wife had killed herself, as he was sure that she would have killed him and their daughter too. She had told him that she liked the idea of the three of them dying together.

The statement of Mary Butterfield, Susan's midwife, with her account of the tragedy of Susan's lost children, touched the court. Butterfield described how Elias Lucas had returned home two hours after the birth of their last child and stated that he wished he were not married: if he had known the troubles that would come his way with marriage to Susan he would not have proceeded, even if her father had given her a dowry of £1,000. Butterfield added:

I told him not to say anything then, as it was a difficult time. This was not in the room where his wife was. He afterwards went to her room and said the same to her, I believe. He then came down and went out to work. I found his wife crying. On the Sunday after he asked me if the child was likely to live or die. I said I thought it did not look like a dying child. I went away on Monday. The deceased had a good getting-up.

Despite this, the baby had died and further rumours spread around the village that it too had been the victim of foul play. Mary Butterfield's daughter, also called Mary, took over from her mother and stayed for some days with Susan Lucas. She stated that, âLucas had eight pigs. I used to feed them. He came home one day in the week and said he thought the pigs grew well, and he would keep the little cad-pig (the least of the lot) till he married again, and have a green leg of pork for his dinner. He said he should marry this Mary Reeder, and went into the house. So did I.' She went on to say that Lucas told his wife he would keep this cad-pig until he married her sister. Sarah had said that it would never come to pass, for they never would allow him to marry her sister. But Mary also admitted that she had only heard him say this on that occasion and she had not thought that he sounded serious. Equally, she couldn't comment about to whom she may have repeated this story, so which of the following witnesses were genuine and which were repeating gossip is impossible to judge. It is fair to say though that some of the comments, that Lucas was reported to have made, would have been shortsighted coming from someone contemplating murder.

Two young women, Anne Ives and Emma Brown, claimed to have bumped into Lucas when they were on their way to Haverhill and said that he had told them that he had a bastard child coming, had been sick of married life from the first night and wanted to get rid of his wife, wishing she would die or go away. Both women denied seeing Mary Butterfield before their court appearances.

Elizabeth Webb, another Castle Camps resident, recounted a conversation with Lucas that initially seemed more in his favour. According to her account, he had explained how the three messes had already been made when he arrived home and that he had been told to take the largest. Mary had taken the next and his wife the remaining one. His had contained sugar, but the other two had salt and pepper. His wife had complained at the taste of hers and eventually he put it down for the cat. But instead of continuing in his favour, Elizabeth Webb reported that Lucas had commented to Susan, âDamn it, that does not taste bad; I would eat mine if it killed me.' This was reprinted in newspaper and handbill accounts and the public were encouraged to take it as a wicked private joke shared with his lover. Lucas was further damned by public opinion when it was reported that he was full of levity during the trial, often turning towards friends in the gallery and laughing out loud when a tin box containing part of his dead wife's digestive tract was produced.

In his closing statement Mr Couch, speaking for the defence, argued that there had been insufficient motive shown, and that if the murder had been planned by both parties then the plan must have existed since the previous year when Lucas had acquired the arsenic. If this had been the case, it was inconceivable that the defendants would have been so careless in their conversations. Mr Couch asked the jury to consider whether Susan Lucas had died through self-inflicted poisoning, either deliberately or accidentally.

The jury, however, retired for only a short time before returning a guilty verdict. Mr Justice Wightman then passed the death sentence upon both the prisoners. Lucas's response was to call out, âI am not guilty. Good bye, ladies and gentlemen. I am innocent.'

The next edition of the

Cambridge Chronicle

published a report that Mary Reeder had confessed:

All doubt as to the propriety of the verdict, and the guilt of the two wretched prisoners now awaiting execution in Cambridge county gaol upon this charge, has been set at rest by the confession of the female prisoner, Mary Reeder. Immediately after leaving the dock, this criminal became apparently resigned and penitent, and on one or two occasions gave vent to observations indicative of a desire to unburthen her mind of the load which oppressed it.

On Tuesday evening she expressed a wish to see her father and he accordingly attended on Wednesday morning, and was admitted to an interview with her in the presence of the reverend chaplain and the matron of the gaol. The presence of the chaplain appeared to act somewhat as a restraint upon her freedom of speech, so he withdrew, leaving her alone with her father and the matron; and then she acknowledged to her father that it was her hand that put the poison in her sister's mess, and attributed the desire to be rid of her to an illicit connection that existed between herself and the male prisoner, Lucas.

This connection, she said, had not taken place since Christmas last, and she most strenuously denied that she was in the family way. She has not in terms accused her partner in crime of inciting her to the commission of the deed, but she has done so by implication. She is now quite resigned to the fate that awaits her, and appears fully cognisant of the enormity of her offence.

She states that she made up her mind to commit the crime only a few minutes before its execution, and that she has not the slightest wish to live. She has paid marked attention to her religious duties. Yesterday, Good Friday, she was present in chapel in the morning, but fainted during the service and remained in her cell in the afternoon. She is constantly watched, a female attendant being with her by day and two throughout the night.

While awaiting execution she made several statements, variously saying that she alone had poisoned her sister then saying that she had committed the crime on Lucas's instruction. She claimed to have asked Lucas, âDo you think there is any harm, Elias, in poisoning for love, as Catherine Foster

4

did?' to which he replied, âNo.' She claimed she had asked him what quantity of arsenic was needed to poison a person and he had replied, âas much as will lie on a shilling.'

Three days before the execution Mary Reeder sent for the chaplain and in the presence of visiting justices stated that the murder was solely her doing and that Lucas had no involvement in the crime. This statement was passed to the Secretary of State, Sir George Grey, who had also received several petitions asking for the capital sentence to be lifted. A reply eventually came on the morning of the execution: a letter arrived at the gaol to say âthat it was the opinion of the learned judge who tried the case, that both the prisoners were equally guilty, and therefore the law must take its course'.

When Lucas was informed that there would be no reprieve he replied, âI am glad of it. I am quite prepared to die. I would not now live for £10,000. I know I shall go to Heaven if I die now; perhaps, if I were to live longer, I might not.'

Lucas and Reeder spent their last evening together, talking and strolling around the garden of the governor's house. On returning to their cells Mary went straight to sleep, suffering several convulsive fits but not actually stirring from slumber until 5 a.m. When she awoke she cried for a time and then read from the Bible.

Lucas on the other hand stayed awake, writing letters to his family and to other prisoners. The letter to his family began, âDear Parents, this is the last time that I shall ever communicate to you in this troublesome world, but I hope that I go to rest in God above; my dear brothers and sister and my beloved child, my own flesh and blood; but if we trust in God he will bring all things to pass.' The letters were full of religious reflection and repeated that he was ready and content to die but contained no clear admission of guilt. At 5 a.m. he drank tea then prayed until 11 a.m. when both he and Reeder received communion from Revd Mr Roberts.

Nationally, the case did not attract much attention, but locally it was a different matter; this was to be the first execution for seventeen years5 and the crowds that assembled were the largest in living memory. The streets were reported to be full from 6 a.m. Estimates in the

Cambridge Chronicle

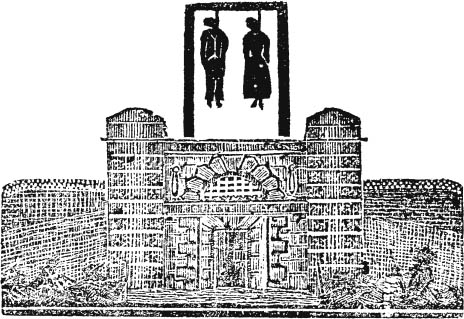

were probably exaggerated, putting the numbers in the region of 40,000. The gallows were erected in front of the debtor's door of the county gaol, Castle Hill, and spectators, including many women and children, gathered on the nearby Castle mound to gain a good view.

The executioner, William Calcraft, 6 pinioned the prisoners then, as the clock struck noon, they left the governor's house. Ahead of the procession was a party of javelin men, closely followed by three or four of the county magistrates, the under-sheriff and the officiating chaplain who read the burial service as he walked. Behind the chaplain walked Calcraft, followed by the officers of the gaol accompanying Lucas, then Reeder, and finally another group of county magistrates.

Lucas was first to climb up the scaffold. He appeared momentarily taken aback by the size of the crowd but, aside from that, remained calm as he took his place. Calcraft pulled the cap over his head and adjusted the rope. Mary waited at the bottom of the steps while this took place. After she had climbed Tyburn's Tree and while the rope was being adjusted around her neck Revd Roberts read the service. At its conclusion both Lucas and Reeder thanked him, saying, âGod bless you sir.' As Calcraft loosened the bolt Lucas whispered, âI am going to God. I am going to God.'