Capitol Men (10 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

Education did ultimately prove one of Reconstruction's quiet successes in South Carolina: by 1877 there were nearly three thousand schools in the state, educating 125,000 young people of both races, and Democrats and Republicans continued to allow a statewide property tax to be levied for that purpose. The strong universal desire for learning, and the fact that the issue of integration was never forced by law, probably accounted for this achievement.

The black delegates acted with moderation on two other key issuesâthe further confiscation of land owned by former rebels and their disenfranchisement; essentially, the freedmen refused to impose additional hardships and kicked the matter to Congress. They knew it would be politically unseemly to appear overly vindictive and no doubt feared that placing restrictions on others' voting rights would undermine the ideal of universal suffrage they themselves so strongly embraced. To some it made no sense that the South, in its greatest hour of need, would not call on the considerable experience of its more prominent white men. Smalls advocated, except in extreme cases, their readmittance to positions of leadership, and, trusting the planters and large landowners more than he did the white yeomanry, looked to a potential coalition between blacks and politically moderate whites; he believed that the state's majority black vote, combined with that of these moderates, would "bury the Democratic party so deep ... there will not be seen even a bubble coming from the spot where the burial took place." As one member asked the gathering, "Can we afford to lose from the councils of state our best men? No, fellow citizens, no! We want only the best and ablest men. And then with a strong pull, and a long pull, and a pull together, up goes South Carolina."

The prospect of "owning a piece of the land that had once owned them" tantalized the freed people like no other aspect of emancipation, and it was an issue that, in response to Richard Cain's efforts, the delegates explored at great length. South Carolina, because of its head start on Reconstruction in the Sea Islands, already had a substantial history of official efforts to provide land to the former slaves. After July 1862 the federal government had begun taxing abandoned plantations in the Port Royal area, posting notices that landowners would have to make an appearance, swear an oath of allegiance to the United States, and remit the tax. It seemed entirely just that large landholders who had been leading secessionists should help bear the cost of the war they had instigated. "Here, beneath these live oaks," mused the

Harper's Weekly

reporter Charles Nordhoff, "they deliberated, they planned ... the ruin of their country; here was nurtured that gigantic and inexcusable crime." Where property owners could not or would not pay, lands were seized. The United States also appropriated lands held by ranking Confederate military or civil officials as well as property owned by some rebel soldiers. An 1865 Freedmen's Bureau inventory prepared for General Rufus Saxton of available properties in the Port Royal area suggests both the displacement and devastation wrought by the war:

Six deserted plantations lie along the "Coosa" river eastward from Port Royal ferry and are perfectly desolate, having neither an inhabitant nor a dwelling...

Estate of Rafe Elliottâlies south east of Gardners Corners; has no houses or other improvements; comprises 800 acres of first quality land. Elliott was a surgeon in the C.S.A. and was killed early in the war...

Oak Pointâbelonged to Henry Stewart, a "hard master" who promoted the rebellion in every possible way except to take up arms himself...

Estate of Hal StewartâLieutenant in the rebel army, the Negroes on his father's place say young "mass Hal" was opposed to the war and only went when "he was scripted"; the place is deserted but several tenements are standing in good order, also cotton and gin houses; there are 600 acres of good land...

John Jenkins Placeâlying directly on the "Combahee road" all gone to ruin and everything grown up to weeds...

In Beaufort, federal commissioners sold almost 17,000 acres subject to sale for nonpayment of taxes at a price of 93.3 cents an acre; blacks

bought about 3,500 acres, as well as about 75 homes in Beaufort for as little as $30 to $1,800. Northern missionaries and speculators who had come south with the Union forces obtained additional properties. South Carolina, along with other Southern states, would continue to shift the tax burden onto large property owners or deny them forms of financial relief, with the idea that this would break up once-vast plantations and make small land parcels available to poor whites and freedmen.

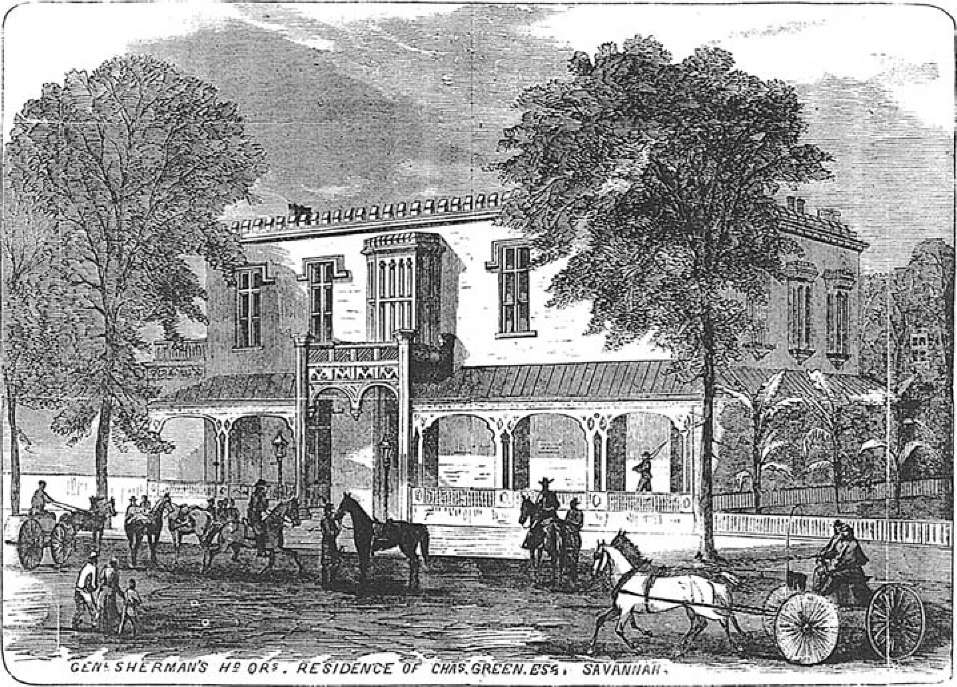

THE SAVANNAH HEADQUARTERS OF GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN

The black population of the Sea Islands had grown substantially during the war as refugees by the thousands arrived from combat zones in Georgia and South Carolina. Concerned about this influx, General William T. Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on January 12, 1865, convened a meeting at Sherman's headquarters in Savannah with black community leaders, chiefly Methodist and Baptist clergymen. When queried as to how the government might best assist the freedmen, the black spokesmen were unanimous in their reply:

Land

! "The way we can best take care of ourselves," they assured the white men, "is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor." In response, Sherman issued Field Order Number 15, establishing the Sea Islands as an area for exclusive black settlement where freedmen and their

families might be settled on forty-acre parcels. (Sherman mentioned that he had some worn-out army mules he would be willing to give the black settlers to help them get started on their plots of landâthe origin of the expression "forty acres and a mule.") Before leaving, the blacks recommended the establishment of separate communities for the two races, for, as one told Sherman and Stanton, "There is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over."

Two months later Congress created the Freedmen's Bureau to deal with the myriad issues now confronting the devastated South and particularly the four million former slaves. In charge were two New EnglandersâGeneral O. O. Howard, who had lost an arm in the Battle of Fair Oaks and was known as "the Christian General" for his work with Northern philanthropies that assisted Southern blacks during the war; and assistant commissioner General Rufus Saxton, the wartime governor of the conquered Sea Islands. With about 300,000 acres of confiscated Sea Islands lands in the bureau's possession, Saxton set about leasing forty-acre parcels, with the stipulation that leasers could buy them at any time. He believed the Southerners had forfeited their land with their ill-conceived rebellion and that blacks deserved the soil on which "they and their ancestors passed two hundred years of unrequited toil." A friend and admirer of Robert Smalls, he felt strongly that black war veterans, who "piloted our ships through these shallow waters, have labored on our forts ... and have enlisted as soldiers in our country's darkest hours," were owed a special debt of gratitude. Smalls had taken advantage of the government's auction of Beaufort properties to purchase the very house where he and his mother had once been slaves.

As General Howard would later note, however, only a tiny fraction of former Confederate lands were ever under federal control; and in any case, the confiscation edicts proved short-lived, for in August 1865 President Andrew Johnson came out against the practice. Johnson allowed all but the most prominent Confederates to seek and obtain presidential pardons and offered to return their seized property. The president's actions did not apply to the Sea Islands, which were covered separately by Sherman's field order, so Johnson directed General Howard to go to South Carolina and work something out between the former property owners and the blacks who had already taken possession of land. Howard suggested to the president that he require Southern men whose property had been returned to "provide a small homestead or something equivalent to each head of family of his former slaves; but," as Howard remembered, "President Johnson was amused and gave no

heed to this recommendation. My heart ached for our beneficiaries, but I became comparatively helpless to offer them any permanent possession ... Why did I not resign? Because I even yet strongly hoped in some way to befriend the freed people."

Reconstruction would be filled with examples of how the federal government backed away from its promises to the freedmen, but none may have been as heart-rending as the scene on Edisto Island in fall 1865 when the "Christian General" had to inform loyal blacks, gathered in a village church, that they would have to forfeit their claim to the land and strike labor contracts with their former owners. In the meeting's "noise and confusion," he recalled, "no progress was had till a sweet-voiced Negro woman began the hymn, 'Nobody knows the trouble I seen, nobody knows but Jesus...'"

The singing calmed the meeting, but when Howard began to address the assembled freed people, "their eyes flashed unpleasantly, and with one voice they cried, 'No, no!'...One very black man, thick set and strong, cried out from the gallery, 'Why, General Howard, why do you take away our lands? You take them from us who are true, always true to the government! You give them to our all-time enemies! That is not right!'"

After the first of the year, a newly arrived federal officer, General Daniel E. Sickles, ordered all freedmen to move off the property they held "illegitimately" or face immediate eviction. Some freedmen were able to hold on to their land if they had purchased it outright and held titles; others were offered less desirable sites possessed by the government. Robert Smalls was active in making these alternative lands available. But by and large, the dream of the forty-acre land plots had ended. Of the almost forty thousand freedmen who were settled on Sea Islands lands because of Field Order Number 15, only fifteen hundred were ultimately deemed to have valid titles.

Other opportunities did open up. In 1866 Congress passed the Southern Homestead Act, making forty-six million acres owned by the United States in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana available in eighty-acre sites at a cost of $2.50 an acre. But much of the land was too expensive or too poor in quality, and freedmen lacked the capital to dredge, drain, or otherwise transform it into arable plots. Hopeful blacks who relocated with the idea of acquiring such property often were forced by economic necessity to accept labor contracts from nearby whites.

It was becoming increasingly clear that most of the desirable land in

the South would remain in the hands of the landowning class that had held it previously. Many Northern Republicans felt that this repudiated the whole purpose of fighting and winning the Civil War. "Of what avail would be an act of Congress totally abolishing slavery, or an amendment to the Constitution forever prohibiting it, if the old agricultural basis of aristocratic power shall remain?" asked the Indiana congressman George W. Julian. "Real liberty must ever be an outlaw where one man only in three hundred or five hundred is an owner of the soil."

To Julian's colleague from Pennsylvania, Thaddeus Stevens, confiscation still seemed the best way to rectify this imbalance, for Stevens envisioned Reconstruction not as a time simply to patch and mend America but as an opportunity to perform reconstructive surgery. The chief of the House Radicals and perhaps the purest revolutionary of the postwar era, Stevens was an intimidating congressional leader. He moved awkwardly because of a clubfoot, a lifelong disability, and, robbed of his natural hair by a scalp infection, he wore an imposing wig, which accentuated the hatchet-sharp features of his face. The

New York Herald

called him "a strange and unearthly apparitionâa reclused remonstrance from the tomb ... the very embodiment of fanaticism," but his friends claimed that his handicaps were the source of his hatred of all injustice. He had been in the forefront of many key advances of the eraâthe Confiscation Acts, the arming of black troops, and the enfranchisement of the freedmen. Some historians suggest that President Lincoln valued the prickly Stevens for his willingness to confront difficult issues head-on, in order that the president's own efforts, trailing just behind, might better appear conciliatory. Stevens was most widely known for his role in engineering the 1868 impeachment of Andrew Johnson, nominally for violating the Tenure of Office Act, but really for failing to lead a program of Reconstruction that was acceptable to Congress.

While the franchise was frequently cited as the key to establishing the freedmen in the South, Stevens feared that even with the vote, black Southerners without land would remain vassals; land confiscation would readjust the region's economy and labor practices while providing poetic justice for the slaves. In a speech in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Stevens explained that if the land holdings of seventy thousand of the key rebels in the former Confederacy were confiscated, it would make enough acres available for redistribution to as many as one million freedmen, with plenty of land left over to be sold at $10 per acre both to blacks and also to poor whites. The latter deserved consideration, Stevens felt, because they had been buffaloed by the Southern

aristocrats into fighting an un-winnable war. The income from these sales could pay down the national debt. To those who might question the wisdom of dispossessing the planters, Stevens insisted such a measure made more sense than cockeyed migration schemes to colonize in some foreign land four million black Americans "native to the soil and loyal to the government." Stevens had an ally in the Boston abolitionist Wendell Phillips, who believed "this nation owes the Negro not merely freedom; it owes him land," and that black Americans knew this best of all, for their "instincts are better than our laws." Phillips saw "what few public men in the America of his time appear to have realized," notes his biographer Ralph Korngold, "that economic power was the foundation of political powerâthat if the land remained in the hands of the planter aristocracy, it would be a question of time before they again ruled the South."