Capitol Men (65 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

While Lynch had the satisfaction of knowing he had tried to set the historical record straight, Richard Cain of South Carolina lived to see the partial realization of his own long-held dream, that of enabling people of color to own their own land. Having watched his plans for congressional underwriting of land distribution and the state's own land commission flame out ingloriously, Cain in 1871 founded his own land development company. It was a project launched perhaps less on sound business principles than on Cain's charisma and the support of his religious followers, but it would see tangible results.

The scheme began, legend has it, with an epiphany beside a railroad track. Daddy Cain was leaving Charleston one day in the company of six

other A.M.E. church trustees when their train stopped for wood and water about twenty miles west of the city at a depot known as Pump Pond. Glancing out the window, he became intrigued by a land-for-sale sign, and to his colleagues' surprise, insisted they immediately get off the train.

Cain ultimately purchased about two thousand acres of land around Pump Pond. Renaming the location Lincolnville, he subdivided it into lots of two to ten acres and offered them for sale at reasonable prices to settlers who agreed to clear their own property and erect homes. Over the next decade Cain sold about sixty of these lots, including one for the construction of an A.M.E. church. Unfortunately, he had begun selling off land parcels in Lincolnville before he could make the first payments on the land, which were due six months after the purchase agreement. Therefore a grand jury indicted him for taking money under false pretenses, that is, selling land that he did not himself own. He was arrested, but his legal counsel and friend, Robert Brown Elliott, arranged for Cain's case to be dropped under the condition the money be refunded.

When the

New York Times,

reporting on Cain's troubles on June 15, 1874, noted that, "It can very safely be said that South Carolina has more criminals in office than any other state in the Union," Cain fired back a lengthy letter, which the newspaper published. "I have settled more colored people in comfortable houses than any other man in the state," he asserted, "and not one family have lost a dollar by any sale which I ever made to them. Anyone may go to South Carolina today and find the people who know me, and they will testify to the facts. The village of Lincoln[ville], twenty miles from Charleston, is a settlement of colored people. If your correspondent will take the trouble to go there he will find 40 odd families comfortably situatedâa church, a school, and a most happy and prosperous community, and not one of them will charge me with defrauding them."

Despite the long-ago retraction of General Sherman's Field Order Number 15, the mismanagement that plagued the state land commission, and the quixotic nature of real estate ventures like Lincolnville, South Carolina fared surprisingly better than most other states in promoting black ownership of land during Reconstruction. The land commission had bought 168 plantations, for a total of almost ninety-three thousand acres, and about two thousand black families were able to take advantage of the land offered for sale on reasonable terms. Between these efforts and the land forfeitures of the immediate postbellum period, it is estimated that four thousand black South Carolina families

obtained land in the decade or so following the war, as compared with the thirty thousand who had done so across the South by 1870. By the 1890 census, the number of landholding black South Carolinians had more than tripled, as families subdivided lands under their control and whites continued to sell off small parcels of once-vast plantations.

Lincolnville, notwithstanding its rocky start, was by the mid-1880s a nearly all-black town of one hundred homes, and the community Cain had brought into being maintained its growth even after he died in Washington in 1887. Today, it remains a biracial working-class enclave of suburban Charleston, where residents chiefly own their own property; many continue to honor the locale's history, which is ennobled by an "official town poem":

Seven men of color had a dream, where men could live and toil

Among the stately pines that stand, enriched infertile soil,

Soil that had been nurtured by those who fought and died,

Oh Lincolnville, Oh Lincolnville, what heritage and pride.

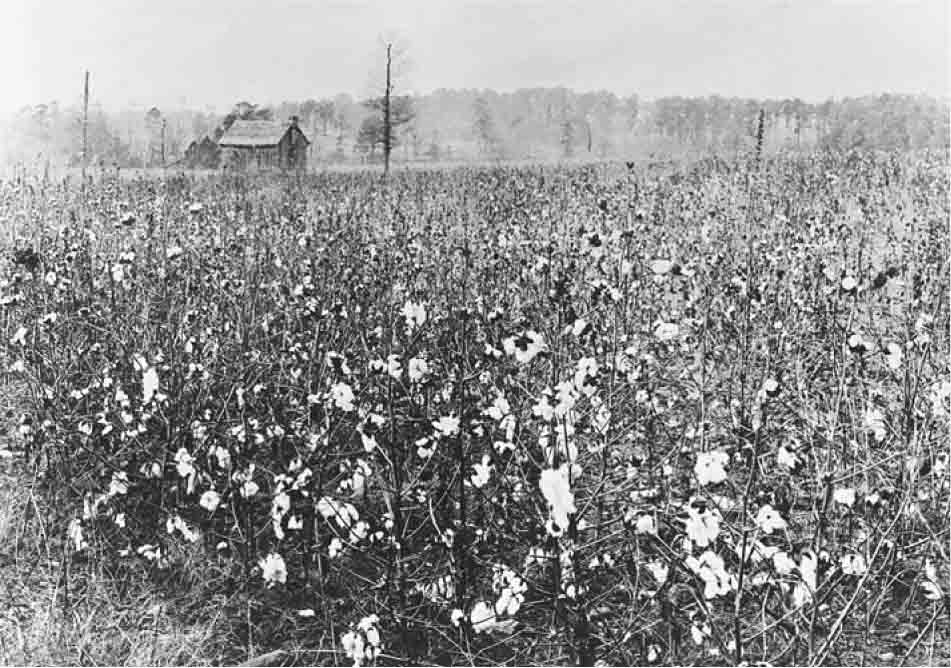

THE PROSPECT OF "OWNING A PIECE OF THE LAND THAT HAD OWNED THEM" TANTALIZED THE FREE PEOPLE.

Cain's insistence on land for South Carolina's freedmen and even the validity of the land commission he'd done so much to instigate were to an extent later vindicated by Carol Bleser, a researcher who in the 1960s met with descendants of some of the original land commission settlers. They resided in an upcountry hamlet known as Promised Land, created in 1870 and consisting of seven hundred acres sold by the commission; by 1872 fifty black families had settled there, paying ten dollars down for farms of fifty to one hundred acres. Unlike the Sea Islands, with their overwhelming black majority, Promised Land was situated in an area where blacks were in the minority and tended to reside in isolated settlements. "Those we talked to were devoid of the embarrassment often felt by Negroes who have had the color line constantly emphasized in meeting white people," Bleser reported. "The possession of land gave them a sense of self-assurance and a certain feeling of equality, both attitudes usually lacking in black tenants and urban workers in the South."

According to Bleser, Promised Land settlers thrived in part by having little to do economically with the surrounding whites. Instead of raising a potentially profitable cash crop like cotton, they diversified their agriculture and concentrated on subsistence farming, growing vegetables and corn and keeping livestock. Crop diversity protected them from the vagaries of the cotton market and allowed them to steer clear of the ruinous debt that haunted many black sharecroppers; they also were able to avoid buying seed, fertilizer, and other goods at overpriced plantation stores. "The genius of this kind of farming," another researcher would conclude, "was that it kept them from getting trapped in the 'crop lien' system that destroyed so many other families, both black and white. They did not get rich, but they endured."

Like P.B.S. Pinchback and John Roy Lynch, many black figures prominent in Reconstruction ultimately drifted away from the South, relocating to Washington, New York, or Chicago. A notable exception was Robert Smalls. His political career at an end following the Tillman-dominated constitutional convention of 1895 in South Carolina, he returned to live out the remainder of his life in Beaufort, in the same house on Prince Street where he and his mother had once served as slaves and which Smalls had purchased at government auction in 1864. Smalls's wife, Hannah, died in 1883, and in 1890 he married Annie Wigg, a teacher from Savannah, whom the

News & Courier

considered "an exceedingly handsome woman of respectable connections"; they had a son, William. Of the three children from his first marriage, Robert Jr. had died as a child, Sara became a music teacher, and Elizabeth, who

had served as her father's secretary in Washington, married the editor of the

Beaufort Free South;

when her husband died she became the Beaufort postmistress.

President William McKinley, for whom Smalls had campaigned, appointed him collector of customs for the port of Beaufort, a position of authority and extensive patronage that suited Smalls well. Whatever local observers thought of his politics, there was no question that Smalls was devoted to his Sea Islands community and its people; from long habit, it seems, he never stopped thinking of them as his constituents. When a hurricane swept over the islands in late August 1893, drowning four hundred men, women, and children and causing an estimated $2 million in damage, Smalls assumed a leading role in the rescue and recovery. "These sea islands are the homes chiefly of negroes who by thrift and industry have made themselves homes, with no one to molest or make them afraid," Smalls wrote of his friends and neighbors. "In one night all has been swept away."

With the turn of the century Smalls remained a familiar figure in the scenic coastal town, a genial old war hero whose most visible public role arrived each May 30, Decoration Day, when he led a procession to the national cemetery just beyond the city limits. The cemetery was the largest enduring testament to the substantial federal presence in Beaufort during the Civil War, as it contained the remains of Union dead from Pennsylvania, Indiana, New York, and numerous other Northern states, as well as African Americans who had served with the federal forces. For the occasion, blacks from the vicinity would pour into Beaufort, and Smalls, now a portly, stooped, but still exceedingly proud man, strapped on his sword and other ceremonial effects and marched at the head of the Beaufort Light Infantry, up Carteret Street to the graveyard. Later there would be a reception at his house, perhaps with distinguished out-of-town visitors. One year he arranged for Booker T. Washington to attend. Surely Washington had Smalls in mind when he observed that "one of the surprising results of the Reconstruction Period was that there should spring from among the members of a race that had been held so long in slavery, so large a number of shrewd, resolute, resourceful, and even brilliant men, who became, during this brief period of storms and stress, the political leaders of the newly enfranchised race."

Lionized as he was in Beaufort, however, Smalls was made to ride Jim Crow when he traveled to Columbia or Charleston by train, seated in a dirty coach with cigar stubs on the floor and broken windows; in 1904

he was told to move to the back of a Charleston streetcar. As he had in Philadelphia forty years earlier, he chose to get off rather than be humiliated, but this time no citywide protest gathered to defend his rights.

Smalls's long connection with federal patronage finally ran out in 1913, when, with the advent of the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson, he lost his post as a customs official; at the same time his health began to deteriorate. It was said that as long as he could muster the strength, prior to his death in February 1915, he liked to visit the local schoolhouse set aside for use by black students, where he urged the youngsters to take seriously the opportunity for education he had never had. Invariably, the children reported to their parents that "the General" had come by again, telling the story of the great war and the night he had run the Confederate ship

Planter

out of Charleston Harbor.

Beaufort still talks of how, in the days immediately after the end of that conflict, Jane McKee, the wife of Smalls's former master, showed up at the house on Prince Street late one evening, disoriented and without means. Smalls took her in. Mrs. McKee, apparently unable to countenance a world so utterly changed, continued to believe that she was living in earlier times, and Smalls allowed her to stay with him in her old house until her death, never confronting her with the fact that a terrible war had been fought, that slavery had ended, and that her former slave had gone off to the nation's capital to serve in Congress, make laws, and confer with presidents.

The story may well be apocryphal, but Smalls did assist Jane McKee and other members of the McKee family during Reconstruction, and there would have been a kind of elegant symmetry to the fact that Smalls, who in a sense kept Reconstruction alive in Beaufort longer than anywhere else in the South, was at the same time maintaining a private fantasy of antebellum life for his former owner's widow. It was a deception only the "Boat Thief" could have managed, or would have been gracious enough to perform.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

T

HE LIBRARIANS AND ARCHIVISTS

at dozens of Southern research centers have been enormously generous in responding to my requests for help and information. In particular I wish to thank Ms. Grace Cordial of the Beaufort, South Carolina, Township Library and the archivists at the South Carolina Room of the Charleston Public Library. I was also welcomed at the Charleston Historical Society; the South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina in Columbia; the Clemson University Library; the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson; the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and the Louisiana Room at the New Orleans Public Library.

In Washington, I made extensive use of the Manuscripts and Periodical Reading Rooms at the Library of Congress; the Moorland-Spingarn Collection at Howard University; the National Archives (Freedmen's Bureau Records Group 105); and the National Archives branch in Beltsville, Maryland (Department of Justice Records Group 60). I also was able to perform valuable research at the Houghton Library, Harvard University; the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library; and the New York Public Library's Main Research Branch as well as its Prints and Pictures Collection.