Carolina Gold (2 page)

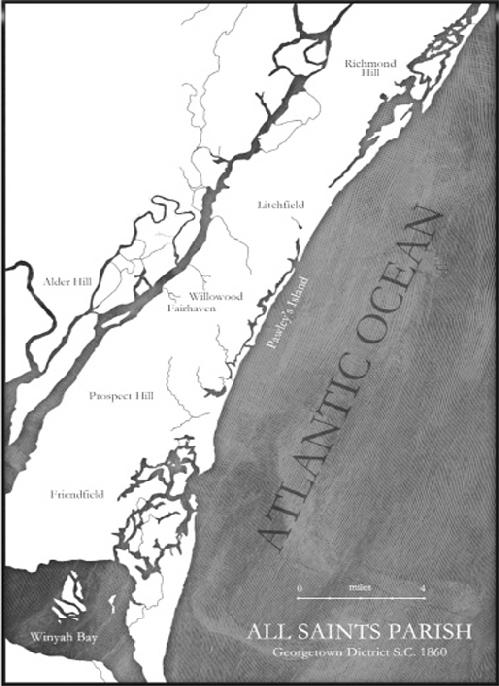

From the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society

Dedicated to the memory of Elizabeth Waties Allston Pringle (1845–1921), whose remarkable life and work inspired this novel

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Author’s Note

Reading Group Guide

Acknowledgments

About the Author

There is in every true woman’s heart a spark of heavenly fire . . . which kindles up and beams and blazes in the dark hour of adversity.

W

ASHINGTON

I

RVING

C

HARLESTON

, S

OUTH

C

AROLINA

3 March 1868

I

n a quiet alcove off the hotel lobby, Charlotte Fraser perched on a worn horsehair chair, nursing a cup of lukewarm tea. A wind-driven freshet lashed the windows and roiled the bruise-colored sky, sending the pedestrians along Chalmers Street scurrying for shelter, jostling one another amid a sea of black umbrellas.

She glanced at the clock mounted on the wall above the polished mahogany reception desk and pressed a hand to her midsection to quell her nerves. An hour remained before her appointment with her father’s lawyer. She had anticipated the meeting for weeks with equal measures of hope and dread, her happiness at the prospect of returning home to the river tempered by fear of what she would find waiting for her. In the war’s crushing aftermath, Fortune had cast her powerful eye upon all of the Lowcountry and passed on by.

A black carriage shiny with rain executed a wide turn onto Meeting Street, the harness rattling as the conveyance halted beneath the porte cochere. The hotel door opened on a gust of wind and rain that guttered the lamps still burning against the afternoon gloom. A young man wearing a rain-splotched cape escorted his lady to the reception desk. He signed the register, then bent to his companion and whispered into her ear. An endearment perhaps. Or a secret.

“Every family has its secrets. And its regrets.”

Charlotte set down her cup. Such strange words from Papa, who had been widely respected for his forthright manner. At the time, she’d had a strong feeling he was trying to tell her something important. Now the memory pinged inside her head like a knife against glass, prickling her skin. But perhaps such talk was merely the product of the laudanum clouding his brain during his final hours.

For weeks following his funeral, Charlotte’s natural optimism lay trapped beneath a cloak of sorrow and she could feel little but the jagged edges of her grief. Now it had softened into something less painful. Acceptance, if not yet peace. And, as the indignities brought on by Reconstruction multiplied, gratitude that death had spared him yet another cruel irony. As former slaves wrestled with the implications of their freedom, their masters were mired in poverty that made their own futures just as uncertain.

Despite her personal hardships, Charlotte was relieved that slavery had ended. At twenty-three she was too young and too inexperienced to assume responsibility for the welfare of so many others. During long nights when sleep eluded her and her problems crowded in, she sometimes doubted whether she could look after herself.

When the clock chimed the three-quarter hour, she gathered her cloak, reticule, and umbrella and crossed the hotel lobby, the sound of her footfalls lost in the thick carpet.

The doorman, a stocky red-haired man of uncertain years, touched the brim of his hat. “Shall I find a carriage for you, Miss Fraser?”

“Thank you, but it isn’t necessary. I’m going to my lawyer’s office just down the street.”

He peered through the leaded-glass door. “Rain’s slacking off some, but the walk will feel like miles in this damp.”

She fished a coin from her bag. “Will you see that my trunks are delivered to the steamship office right away?”

“Certainly.” He pocketed the coin and held the door open for her. “Take care you don’t get a chill, miss.”

She threw her cloak over her stiff crepe mourning dress, stepped from beneath the hotel’s protective awning, and hurried down the street, rain thumping onto the stretched silk of her umbrella. Meeting Street hummed with carriages and drays, freight wagons and pedestrians headed in a dozen different directions. A buggy carrying a dark-skinned woman in a pink-plumed hat raced past, the wheels splashing dirty water onto the sidewalk. At the corner of Meeting and Broad, a Yankee officer stood chatting with two burly Negro men smoking cheroots. Charlotte picked her way along the slick cobblestones, past the remnants of burned-out buildings and the rubble of crumbled chimneys, feeling estranged from a city she knew like the back of her hand.

As long as Papa was alive, she’d felt connected to every street and lane, every shop and church spire, every secret garden beckoning from the narrow shadowed alleys. Now everything had been upended. Nobody was where they were supposed to be and she was floating, adrift in a strange new world with no one to guide her.

She dodged a group of noisy boys emerging from a bookshop and gathered her skirts to avoid the dirty water splashing from the wheels of another passing carriage. Beneath the sheltering awning of a confectioner’s shop, two women watched her progress along

the street, their faces drawn into identical disapproving frowns. No doubt they thought it inappropriate for a young woman to walk on the street unescorted. She lifted her chin and met the older women’s gazes as she passed. If they knew the purpose of her visit to the lawyer, perhaps they’d be even further scandalized.

At the law office, she made her way up the steps and rang the bell.

Mr. Crowley, a wizened man with a bulbous nose and a fringe of white hair, opened the door. “Miss Fraser. Right on time, I see. Do come in.”

She left her dripping umbrella in the brass stand in the anteroom, crossed the bare wooden floor, and took the seat he indicated. She folded her hands in her lap and waited while he settled himself and thumbed through the pile of documents littering his desk.

Through the window she watched people and conveyances making their way along the street, ghostlike in the oyster-colored light of the waning afternoon. Down the block a lantern struggled against the gloom, casting a shining path on the rain-varnished cobblestones. Music from a partially opened window across the street filtered into the chilly office. Somebody practicing Chopin.

She felt a prick of loss. According to their neighbors, the Federals had destroyed her piano on one of their wartime raids up the Waccamaw River. Probably everything else as well. Since the war’s end, the difficulties of travel and her father’s prolonged illness had prevented her from learning firsthand whether anything was left of Fairhaven Plantation.

“Well, Mr. Crowley?” Charlotte consulted the ornate wall clock behind his desk. Captain Arthur’s steamship,

Resolute

, traveled from Charleston to Georgetown only on Wednesdays and Saturdays. She meant to be aboard for tomorrow morning’s departure. If she could ever get an answer from the lawyer. “What about my father’s will?”

Without looking up, he raised one finger. Wait.

She tamped down her growing impatience. Waiting was about all she had been able to do since Papa’s death. That and worrying about how she would make her way in the world alone. Now that the war was lost and all the bondsmen were free, the rice trade that had provided her with a comfortable life was in danger of disappearing altogether. She was trained for nothing else.

At last Mr. Crowley looked up, wire spectacles sliding down his nose. “The will has been entered into the record and duly recognized by the court.” He paged through a file, a frown creasing his forehead.

“But?”

“I’d feel much better if your father had provided a copy of the grant to his barony.” He studied her over the top of his spectacles. “You’re certain he left no other papers behind?”

“No, none.” She felt a jolt of panic. “Does that pose a problem?”

“I hope not. There’s a new law on the books that provides for testimony regarding lost wills and deeds and such, but if you’ve never seen such a document, then you can hardly swear to its existence in court.”

“No, I suppose not.”

“Now that the Yankees have taken over, they can seize whatever they want in the name of Reconstruction.” He snorted. “Reconstruction, my eye. Theft is more like it.” He leaned forward, both palms pressed to his desk, and blew out a long breath. “Lacking proof of your father’s grant just makes it that much easier for them. Frankly I’m surprised he left no record behind. He seemed like a man who left little to chance. But I suppose we all have our shortcomings.”

Charlotte toyed with the clasp on her reticule. As a small child she had thought Papa the perfect embodiment of wisdom, intelligence, and prudence. A man without shortcomings. Only

occasionally had she glimpsed moments in which he seemed lost to time and place, standing apart and alone, an unreadable expression in his dark eyes. She still revered him as the finest man in Carolina, the only man in the world in whom she had absolute faith and confidence. Learning of such a grave oversight had come as a shock.

She met the lawyer’s calm gaze. “I don’t know why the Yankees would want my land now. According to everything I’ve heard, they just about destroyed every plantation on the Waccamaw—and the Pee Dee too.”