Casebook (38 page)

“That’s over,” I said.

She nodded, absorbing the information. “Is he still in Washington?”

“I don’t know where he is.” I shrugged. “Not in our life.”

My bad. The Mims would have said something like

We’re friends now

. I thought of all the trouble our parents took with the divorce, the

We still love each other

s and the

as a family

s. Parents don’t want kids to think people just fall off into anonymity. And they don’t normally. My dad was coming over for dinner the next night.

Boop Two sluffed in with a friend. I’d noticed before that Boop One’s friends looked like her—they wore sweats and leotards and always seemed to know where their legs went. They kept their hair in neat buns or brushed it out long and shiny. Boop Two had her peeps, too. This girl wore hiking boots and fleece. One long thick braid swung on her back.

I heard our mom in the kitchen and thought of the Moleskine. Eli had remembered Zeke’s and Simon’s names, my daily class schedule, for Pete’s sake. With his memory, I shuddered to think what was in that notebook. I hated that the thing existed in our house. Hector had hounded me about sex for our comic. I’d put him off. Even now, I didn’t tell him about the Moleskine, though I wanted to talk about it to someone. But I thought he’d zero in on it for other reasons than just me and my roiled brain. And there was no one else to tell.

After a week, I finally stole the thing and handed it over to him.

His jaw actually dropped, and this time his eyes fell more open, too.

“Did you read it?” he asked.

“No,” I said. I had an aversion.

The way Hector held the small notebook, a finger on the cover, I could tell he felt a tingle. He wanted something for our comic.

“Read it fast,” I said, “so I can replant it before she notices it’s gone.”

In school a day later, Hector showed me a picture. A made bed, the cover nicked in under the pillows. One window. A Canary Island pine outside. That all seemed okay. He gave the Moleskine back. “Finished?” I said, and he nodded.

“Anything I need to know?”

He thought a minute. “Most of it wasn’t even about sex.” They’d had conversations running and on the phone. They’d talked for years, before anything. The monster had written that their relationship rested on a long, deep friendship.

“Right,” I whispered. Not like any friendship I ever want.

I slipped the Moleskine back into the drawer, never to be opened by me again. I rummaged around and in the back found a small leather pillbox, inside of which was

the Ring

.

*

I wondered what the Mims was going to do with it. She never wore it anymore. She had two daughters; she could hardly give it to one of them. But I was glad it was still here, in with the scraps of paper, promises from Eli, and our baby teeth.

Boop Two rallied the Animal Rights Collective to carry signs against Prop 8 with us in front of the polling booths. So it was animal activists in fleece, bunches of girly girls who were also members, and our weird gang from FLAGBTU. A guy in a Cadillac rolled down his windows and called my twin sisters lesbos, ten feet away from real lesbos. Maude thumped the front of his car.

But we lost.

After the polls came in, Hector and I waded through a crowd of girls to my room and closed the door, with a chair hooked up under the knob so they couldn’t enter. This house always seemed fuller than our old one. Hound whimpered against the door, knocking his tail. I finally asked Hector about the Moleskine.

In the beginning, Hector said, the Mims told Eli she had problems. With sex. Hector asked me how much I wanted to hear. Less than I’d heard already, I said.

Eli had made her talk about it. Talk some more, he’d said. Just blab.

It’s pretty bad, she’d told him.

I think of my mother

.

What was so bad about that? I’d known my grandmother. She’d run, pushing my tricycle, wearing a long scarf, the times we’d visited Detroit.

Hector opened his notebook and showed me a sketch of a woman yanking up her T-shirt.

I have to show you. From breastfeeding

.

One smaller than the other.

“He cried the first time,” Hector told me.

Eli

cried

! What was I supposed to do with that?

And after, he sent her a list of ideas. That seemed to involve pillows.

“Maybe I don’t need to hear this.” You’ve heard of dry humping? It turned out there was also such a thing as dry retching.

We were quiet for a while.

He showed me a panel.

Pitched up on his arms, in a bed, Eli asked,

Where are you?

And so I told him. Where I was, was not with him

.

Tell me where you are

, Eli said a lot. He wanted to climb inside her thought bubble, join her there.

I had a headache starting. Rounded brains throbbed against my skull. I shouldn’t know this. She wouldn’t have told me. This is why you shouldn’t break into people’s privacy.

She needed to imagine ugly things

.

I gagged, feeling sick, maybe permanently unhappy. If this was where all our investigations led, I understood: Ben Orion had been right. We’d gone too far.

Hector said Eli found porn on his computer, postage-stamp-sized pictures of young girls. Eli thought a certain type of girl excited her. He said he could tell she was aroused.

A word a person should never hear about one’s mother.

Hector showed me another frame.

A couple in bed.

Most of the time we’re having sex, you’re not even with me

, the man said.

“We can’t use any of this, you know.” I stood up.

Eli talked about getting a real live girl for a threesome. The Mims had freaked.

She tried to explain to him that wasn’t what she wanted at all. He begged her to tell him what she imagined doing to the girl or the girl doing to her.

I put a hand up to stop. But Hector kept on.

She said neither. I imagine

being

the girl, she said. Something had happened in that small apartment in Dearborn. With her

brother and her and their mother in two small rooms, there wasn’t privacy. Sometimes her mother brought home men. I recognized flecks of the story: the working mother, two kids, in the immigrant enclave outside Detroit. Maybe her dials were set then, she told Eli. But she wanted to be with him. Eli. No girl. No one else.

In Hector’s drawing you saw only the gray outline of a couple under covers in bed, their dialogue in bubbles.

Some things happened when I was young and now I have to think of them

.

Why have to?

In order to come

.

In the end, it was a small sad story of accommodation to damage. Not my business. I thought of my dad. He couldn’t have followed her where she went with her eyes closed. My dad was a happy camper. A Once Born. A firstborn. I wanted to be him.

Another panel:

The same made bed again, one window, a pine outside

.

Vibrant romantic hope

, read the caption.

“We’re almost done,” Hector said.

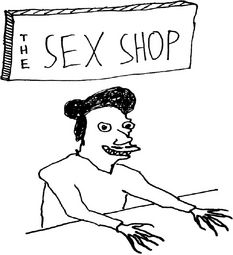

THE SEX SHOP

He’d drawn a young immigrant guy behind the counter; he looked too much like Apu from

The Simpsons

.

So this is all it is

, read the woman’s thought balloon.

“That really happened?” I asked. “They went to a sex shop?”

“Just to see.” Hector nodded. “They didn’t buy anything.”

The last drawing was a spoon with a fortune-cookie fortune in it:

the family romance

.

He fed her dreams

, read the caption.

“I feel bad for your work, man,” I said. “But we’ve got to throw all this out.”

We’d been villains stealing this stuff she wouldn’t want us to know.

Maybe Eli had ruined me.

Hector nodded, respecting my verdict. “We could do a more fantastic version,” he finally said. “Give ourselves superpowers.”

*

That hit some spot and settled me. We still had that

.

70 • The Last Dog

I accepted my life as it was. I didn’t worry anymore about whether the Mims could make dinner, but I had no big hopes for happiness either. She and Eli had mixed themselves together in a way I didn’t understand. Sometimes I thought there had been good in it, too, strands of care along with the deception. I’d seen behind a curtain something small and human, a misshapen child with a smear of dirt on its shin. I was done trying to discover anything. What I didn’t know, I wanted to keep that way.

I turned my attention to school for my senior year. What my dad regularly harped on was true: this was my last chance at a decent college. While Hector and I had messed around all summer, Maude had manually lifted her SAT score another hundred points.

And we still had to deliver a schnauzer.

This last dog fit into my backpack, but he scratched at the fabric,

frantic, a biter and a yapper. Even mean dogs spooked, apparently; madness provided no protection from terror. We went on a Friday and had to make three transfers. On the final leg, we sat at the back of the bus, and I lifted him out.

MAX

, the tag said. I unlatched it. They couldn’t have a number to call that might trace back to us. Max climbed up my chest as if clawing his way to air from underwater. He ripped my shirt.

It’s okay, Max, you’re going to be safe. This guy loves dogs

. Outside the bus windows, the world streamed green and blue. But the word

love

had tripped me. People said

love

all the time. What if Eli had lied about this, too? We knew now that the holidays he said he worked at shelters he was probably just eating. What if he’d really been eating a turkey, that had had a face?

That idea revealed a cliff. He could have taken our pets to the pound and let them die. I told Hector, wanting him to talk me down. But he sank back against the seat as if shot.

“You’re right. He could have been lying. Like the quote-unquote ‘operation.’ ”

The thing’s skull, under its fur, felt paper-thin. The past summer, I’d made a hierarchy of least favorite animals. I hated schnauzers. Hector’s most reviled breed was poodles. “Maybe we shouldn’t release him.” We were almost to our stop.

“We already left a bunch of animals,” Hector said. “You think we’re like those Polish Catholics who delivered up Jews to the Nazis?”

“That once I saw Eli hold dying kittens. He knew how.”

“But what are we thinking believing this when he lied about everything else?”

“Maybe it was his one sweet spot.” Ben Orion would say I was

makin’ fairy tales

. I held Max, shushing him. He was an incredibly nervous animal. We passed long grasses blowing against a chain-link fence. Finally we arrived at our stop. So far we’d left them: