Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Read Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Online

Authors: Tennessee Williams

CAT ON A

HOT TIN ROOF

Tennessee Williams

A N E W D I R E C T I O N S B O O K

Contents

CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light!

DYLAN THOMAS

TO AUDREY WOOD

Copyright © 1954, 1955 by Tennessee Williams

The quotation from Dylan Thomas is from “Do Not Go Gentle Into

That Good Night” in

The Collected Poems of Dylan

Thomas,

Copyright 1952 by Dylan Thomas, published by New Directions.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to

The New York

Times Sunday Drama Section

in which the article

“Person-to-Person” first appeared.

PERSONâTOâPERSON

Of course it is a pity that so much of all creative work is so closely related to the personality of the one who does it.

It is sad and embarrassing and unattractive that those emotions that stir him deeply enough to demand expression, and to charge their expression with some measure of light and power, are nearly all rooted, however changed in their surface, in the particular and sometimes peculiar concerns of the artist himself, that special world, the passions and images of it that each of us weaves about him from birth to death, a web of monstrous complexity, spun forth at a speed that is incalculable to a length beyond measure, from the spider mouth of his own singular perceptions.

It is a lonely idea, a lonely condition, so terrifying to think of that we usually don't. And so we talk to each other, write and wire each other, call each other short and long distance across land and sea, clasp hands with each other at meeting and at parting, fight each other and even destroy each other because of this always somewhat thwarted effort to break through walls to each other. As a character in a play once said, “We're all of us sentenced to solitary confinement inside our own skins.”

Personal lyricism is the outcry of prisoner to prisoner from the cell in solitary where each is confined for the duration of his life.

I once saw a group of little girls on a Mississippi sidewalk all dolled up in their mothers' and sisters' castoff finery, old raggedy ball gowns and plumed hats and high-heeled slippers enacting a meeting of ladies in a parlor with a perfect mimicry

of polite Southern gush and simper. But one child was not satisfied with the attention paid her enraptured performance by the others, they were too involved in their own performances to suit her, so she stretched out her skinny arms and threw back her skinny neck and shrieked to the deaf heavens and her equally oblivious playmates, “Look at me, look at me, look at me!”

And then her mother's high-heeled slippers threw her off balance and she fell to the sidewalk in a great howling tangle of soiled white satin and torn pink net, and still nobody looked at her.

I wonder if she is not, now, a Southern writer.

Of course it is not only Southern writers, of lyrical bent, who engage in such histrionics and shout, “Look at me!” Perhaps it is a parable of all artists. And not always do we topple over and land in a tangle of trappings that don't fit us. However, it is well to be aware of that peril, and not to content yourself with a demand for attention, to know that out of your personal lyricism, your sidewalk histrionics, something has to be created that will not only attract observers but participants in the performance.

I try very hard to do that.

The fact that I want you to observe what I do for your possible pleasure and to give you knowledge of things that I feel I may know better than you, because my world is different from yours, as different as every man's world is from the world of others, is not enough excuse for a personal lyricism that has not yet mastered its necessary trick of rising above the singular to the plural concern, from personal to general import. But for years and years now, which may have passed like a dream because of this obsession, I have been trying to learn how to

perform this trick and make it truthful, and sometimes I feel that I am able to do it. Sometimes, when the enraptured street-corner performer in me cries out “Look at me!,” I feel that my hazardous footwear and fantastic regalia may not quite throw me off balance. Then, suddenly, you fellow performers in the sidewalk show may turn to give me your attention and allow me to hold it, at least for the interval between 8:40 and 11 something

P.M.

Eleven years ago this month of March, when I was far closer than I knew, only nine months away from that long-delayed, but always expected, something that I lived for, the time when I would first catch and hold an audience's attention, I wrote my first preface to a long play. The final paragraph went like this:

“There is too much to say and not enough time to say it. Nor is there power enough. I am not a good writer. Sometimes I am a very bad writer indeed. There is hardly a successful writer in the field who cannot write circles around me . . . but I think of writing as something more organic than words, something closer to being and action. I want to work more and more with a more plastic theatre than the one I have (worked with) before. I have never for one moment doubted that there are peopleâmillions!âto say things to. We come to each other, gradually, but with love. It is the short reach of my arms that hinders, not the length and multiplicity of theirs. With love and with honesty, the embrace is inevitable.”

This characteristically emotional, if not rhetorical, statement of mine at that time seems to suggest that I thought of myself as having a highly personal, even intimate relationship with people who go to see plays. I did and I still do. A morbid shyness once prevented me from having much direct communication with people, and possibly that is why I began to write

to them plays and stories. But even now when that tongue-locking, face-flushing, silent and crouching timidity has worn off with the passage of the troublesome youth that it sprang from, I still find it somehow easier to “level with” crowds of strangers in the hushed twilight of orchestra and balcony sections of theatres than with individuals across a table from me. Their being strangers somehow makes them more familiar and more approachable, easier to talk to.

Of course I know that I have sometimes presumed too much upon corresponding sympathies and interest in those to whom I talk boldly, and this has led to rejections that were painful and costly enough to inspire more prudence. But when I weigh one thing against another, an easy liking against a hard respect, the balance always tips the same way, and whatever the risk of being turned a cold shoulder, I still don't want to talk to people only about the surface aspects of their lives, the sort of things that acquaintances laugh and chatter about on ordinary social occasions.

I feel that they get plenty of that, and heaven knows so do I, before and after the little interval of time in which I have their attention and say what I have to say to them. The discretion of social conversation, even among friends, is exceeded only by the discretion of “the deep six,” that grave wherein nothing is mentioned at all. Emily Dickinson, that lyrical spinster of Amherst, Massachusetts, who wore a strict and savage heart on a taffeta sleeve, commented wryly on that kind of posthumous discourse among friends in these lines:

I died for beauty, but was scarce

Adjusted in the tomb,

When one who died for truth was lain

In an adjoining room.

He questioned softly why I failed?

“For beauty,” I replied.

“And I for truth,âthe two are one;

We brethren are,” he said.

And so, as kinsmen met a night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

Meanwhile!âI want to go on talking to you as freely and intimately about what we live and die for as if I knew you better than anyone else whom you know.

Tennessee Williams

1955

CHARACTERS OF THE PLAY

MARGARET

BRICK

MAE

, sometimes called Sister Woman

BIG MAMA

DIXIE,

a little girl

BIG DADDY

REVEREND TOOKER

GOOPER

, sometimes called Brother Man

DOCTOR BAUGH

, pronounced “Baw”

LACEY

, a Negro servant

SOOKEY

, another

Another little girl and two small boys

(The playing script of Act III also includes

TRIXIE

, another little girl, also

DAISY

,

BRIGHTIE

and

SMALL

, servants.)

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

was presented at the Morosco Theatre in New York on March 24, 1955, by The Playwrights’ Company. It was directed by Elia Kazan; the stage sets were designed by Jo Mielziner, and the costumes by Lucinda Ballard. The cast was as follows:

| LACEY | M AXWELL G LANVILLE |

| SOOKEY | M USA W ILLIAMS |

| MARGARET | B ARBARA B EL G EDDES |

| BRICK | B EN G AZZARA |

| MAE | M ADELEINE S HERWOOD |

| GOOPER | P AT H INGLE |

| BIG MAMA | M ILDRED D UNNOCK |

| DIXIE | P AULINE H AHN |

| BUSTER | D ARRYL R ICHARD |

| SONNY | S ETH E DWARDS |

| TRIXIE | J ANICE D UNN |

| BIG DADDY | B URL I VES |

| REVEREND TOOKER | F RED S TEWART |

| DOCTOR BAUGH | R. G. A RMSTRONG |

| DAISY | E VA V AUGHAN S MITH |

| BRIGHTIE | B ROWNIE M C G HEE |

| SMALL | S ONNY T ERRY |

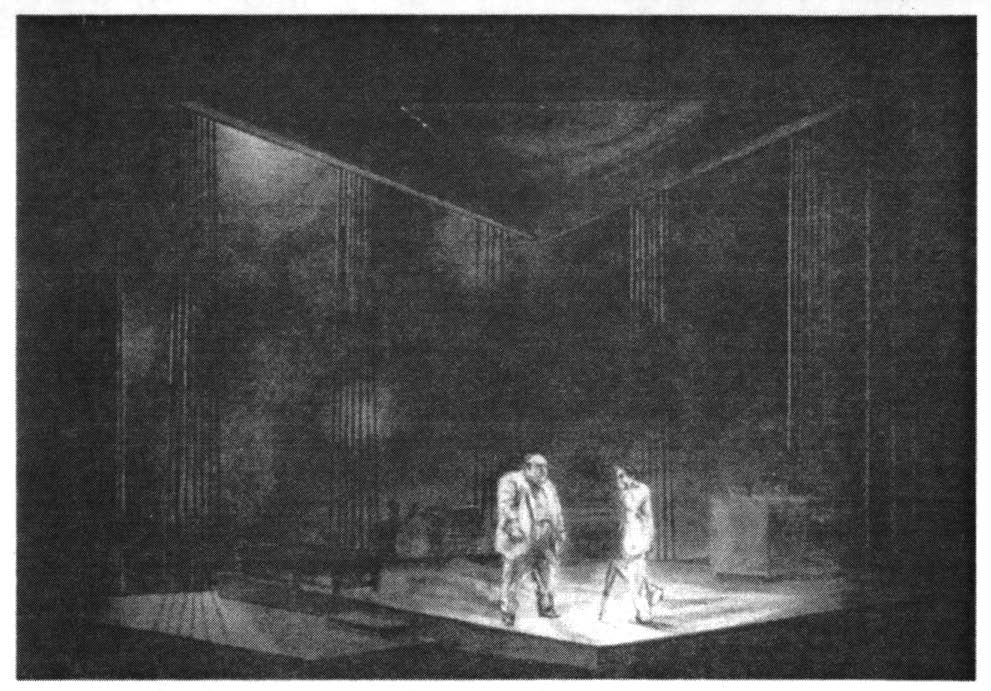

SKETCH OF STAGE SETTING FOR THE NEW

YORK PRODUCTION BY JO MIELZINER

NOTES FOR THE DESIGNER

The set is the bed-sitting-room of a plantation home in the Mississippi Delta. It is along an upstairs gallery which probably runs around the entire house; it has two pairs of very wide doors opening onto the gallery, showing white balustrades against a fair summer sky that fades into dusk and night during the course of the play, which occupies precisely the time of its performance, excepting, of course, the fifteen minutes of intermission.

Perhaps the style of the room is not what you would expect in the home of the Delta's biggest cotton-planter. It is Victorian with a touch of the Far East. It hasn't changed much since it was occupied by the original owners of the place, Jack Straw and Peter Ochello, a pair of old bachelors who shared this room all their lives together. In other words, the room must evoke some ghosts; it is gently and poetically haunted by a relationship that must have involved a tenderness which was uncommon. This may be irrelevant or unnecessary, but I once saw a reproduction of a faded photograph of the verandah of Robert Louis Stevenson's home on that Samoan Island where he spent his last years, and there was a quality of tender light on weathered wood, such as porch furniture made of bamboo and wicker, exposed to tropical suns and tropical rains, which came to mind when I thought about the set for this play, bringing also to mind the grace and comfort of light, the reassurance it gives, on a late and fair afternoon in summer, the way that no matter what, even dread of death, is gently touched and soothed by it. For the set is the background for a play that deals with human extremities of emotion, and it needs that softness behind it.

The bathroom door, showing only pale-blue tile and silver towel racks, is in one side wall; the hall door in the opposite wall. Two articles of furniture need mention: a big double bed which staging should make a functional part of the set as often as suitable, the surface of which should be slightly raked to make figures on it seen more easily; and against the wall space between the two huge double doors upstage: a monumental monstrosity peculiar to our times, a

huge

console combination of radio-phonograph (hi-fi with three speakers) TV set

and

liquor cabinet, bearing and containing many glasses and bottles, all in one piece, which is a composition of muted silver tones, and the opalescent tones of reflecting glass, a chromatic link, this thing, between the sepia (tawny gold) tones of the interior and the cool (white and blue) tones of the gallery and sky. This piece of furniture (?!), this monument, is a very complete and compact little shrine to virtually all the comforts and illusions behind which we hide from such things as the characters in the play are faced with. . . .

The set should be far less realistic than I have so far implied in this description of it. I think the walls below the ceiling should dissolve mysteriously into air; the set should be roofed by the sky; stars and moon suggested by traces of milky pallor, as if they were observed through a telescope lens out of focus.

Anything else I can think of? Oh, yes, fanlights (transoms shaped like an open glass fan) above all the doors in the set, with panes of blue and amber, and above all, the designer should take as many pains to give the actors room to move about freely (to show their restlessness, their passion for breaking out) as if it were a set for a ballet.

An evening in summer. The action is continuous, with two intermissions.