Catastrophe (24 page)

Authors: Dick Morris

Some of the congressman’s colleagues in the House were not amused by Rangel’s self-celebrating earmark. Congressman John Campbell challenged Rangel: “You don’t agree with me or see any problem with us, as members, spending taxpayer funds in the creation of things named after ourselves while we’re still here?”

319

“I would have a problem if

you

did it,” Rangel replied, “because I don’t think that

you’ve

been around long enough that having your name on something to inspire a building like this in a school.”

Rangel refused to see anything wrong with the project. “I cannot think of anything I am more proud of,” he said.

320

CBS News quoted from promotional brochures for the Center, which promised:

a new “Charles B. Rangel Center for Public Service,” the “Rangel Conference Center,” “a well-furnished office for Charles Rangel,” and the “Charles Rangel Library” for his papers and memorabilia. It’s kind of like a presidential library, but without a president. In fact, the brochure says Rangel’s library will be as important as the Clinton and Carter libraries.

321

Really, Charlie? That’s how you see yourself?

As the debate on the earmark was ending, Congressman Campbell summed up Rangel’s hubris: “We call it the ‘Monument to Me,’ because…Congressman Rangel is creating a monument to himself.”

322

Perhaps Rangel became so obsessed with the monument to himself that he lost sight of what was acceptable conduct for a congressman.

It should go without saying that no member of Congress should be permitted to sponsor an earmark for—that is,

spend the taxpayers’ money on

—a personal project.

But when the taxpayers’ money was not enough to fund Rangel’s Monument to Me, the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee decided to hit up his good buddies at AIG and other corporations for big donations.

THE CONGRESSMAN AND AIG

As mentioned above, Charlie Rangel wasn’t always so critical of AIG. The company had provided campaign money to him over the years and he and its former CEO, Maurice Greenberg, had become friends. In fact, according to published reports, Greenberg had helped to steer a $5 million contribution from a foundation to Rangel for his eponymous Center.

But Rangel wanted more. And so did City University, which, according to the

New York Times

, was hoping to get a $10 million contribution from AIG.

323

A meeting was set up, and Rangel made a pitch for a contribution. It’s what happened next that has raised questions.

One of the attendees at the meeting wrote to Rangel and asked for his support on a tax measure that would be worth millions to AIG, a tax measure that Rangel had opposed in the past. And guess what? He changed his position. Rangel claims that he had decided to change his mind about the bill well before he ever received the AIG letter.

Of course.

You see the problem: The chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, who has almost unilateral power over tax legislation, is meeting with a company that wants a tax break. And the purpose of the meeting is for Charlie to beg for money. It doesn’t look good, does it?

Not surprisingly, AIG made assurances that its request had nothing to do with Rangel’s own bid for $10 million for his center.

Of course not.

Because if a legislator does something as a

quid pro quo

, it is a crime. And neither Rangel nor AIG would ever want to get involved in such a thing.

Probably squeamish about the appearance of such a deal, AIG never donated the $10 million. But Rangel must still have been grateful for the $5 million AIG’s former chairman Greenberg had steered his way.

Rangel got into even more trouble over his aggressive fund raising tactics.

The New York Times

reported that Rangel had used his congressional stationery indicating that he was Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee to solicit funds for foundations. According to the

Times:

one was sent to an administrator at the Starr Foundation, where Mr. Greenberg serves as the chairman. The foundation did not make a donation in 2006…. In March 2007, two months after Mr. Rangel had been elevated to Ways and Means chairman, he wrote a letter directly to Mr. Greenberg, using his Congressional stationery. By the end of the year, Mr. Greenberg had pledged $5 million, by far the largest contribution to a project that has raised $11 million to date.

324

After widespread reports of Rangel’s practice of using his congressional imprimatur to solicit funds appeared in the media, Rangel initially defended the practice, declaring it legal. But he then changed his position and asked the House Ethics Committee to investigate the matter. That was in July 2008—and so far there’s been no finding by that committee.

Don’t hold your breath.

What is it about building a Monument to Me that makes our elected officials go begging to the nearest corporate donor?

Bill Clinton, for example, spent his last years in office hitting up every last rich guy and Middle East leader for contributions to his library. What’s wrong with that? Well, first, he was raising money directly from the White House while he still had the power to do major favors. And then he arrogantly did it in secret and defiantly refused to release the names. It doesn’t inspire confidence in our system, does it? When Clinton granted a last-minute pardon to the fugitive Mark Rich that circumvented the Justice Department mechanism, there was widespread suspicion that it was bought and paid for by Denise Rich’s $450,000 contribution to the library (as well as gifts of furniture and campaign contributions to Hillary).

And Charlie Rangel isn’t the only man on the Hill with his very

own Monument to Me. Senators Richard Shelby (R-AL) and Thad Cochran (R-MS) have also gotten earmarks for projects bearing their names while they still serve in the Senate. This practice is both tasteless and disgraceful.

Right now, there’s frantic fund-raising going on to build—albeit from private money—a new Edward M. Kennedy Institute of the Senate in Boston. According to the

Boston Globe:

Drug companies, hospitals, and insurance firms have helped to amass $20 million to finance a nonprofit educational institute in Boston that will honor Senator Edward M. Kennedy…. The biggest donation has been $5 million from Amgen Inc., a national biotechnology drug firm based in California that depends heavily on federal healthcare policies and Medicare prescription drug reimbursements for its profits…. The Service Employees International Union gave $2.5 million, and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America pledged $1 million. The Novartis US Foundation gave $250,000, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts gave $200,000.

325

QUESTION: What do all of these groups have in common?

ANSWER: They all are regulated (at least partially) by the federal government, seek money from it, and/or seek legislation in Congress.

QUESTION: Who’s the chairman of the Labor, Health and Education Committee that makes decisions on all health care–related bills?

ANSWER: The one and only Senator Kennedy.

That’s the problem.

Though Senator Kennedy himself has not been involved in the fund-raising, his son, Ted Kennedy Jr. represented him at a fund-raising dinner. Those who are making the fund-raising calls told the

Globe

that there were no ethical issues with the fund-raising efforts, since the senator himself had no role in overseeing it. They also indicated that they intended to reach out to the financial and entertainment industries for contributions, too.

But segregating the senator is not enough. If any of his family members and staff are attending the fund-raisers and speaking to possible donors, there’s at least the appearance of an ethical problem, isn’t there?

There should be a broad prohibition against any public official doing any private fund-raising for something that relates to him or his family, whether it’s named after him or not. Public officials shouldn’t be able to raise money from any person or entity that has business before Congress.

It’s that simple.

RANGEL AND THE OIL COMPANY TAX BREAK

But the AIG solicitation isn’t the only source of concern over Charlie Rangel’s questionable mix of tax policies and personal solicitations.

It seems that Rangel had personally sought another contribution to his new school. This time he met with Eugene M. Isenberg, the chief executive officer of Nabors Industries, a petroleum exploration company that had moved its drilling operations offshore after 9/11 to avoid federal taxes. Although Rangel had been publicly critical of the company in 2004, by the time Isenberg pledged $1 million for his school in 2007, Rangel was firmly in support of the valuable tax loophole that Isenberg was seeking to keep.

326

It’s not just that Rangel changed his mind. The circumstances and context of his meetings with Isenberg were appalling. On the very morning that the Ways and Means Committee would consider the bill that would benefit Nabors, Rangel met with Isenberg to discuss his contribution to the school. After the discussion was finished, the pair moved across the room to meet with Nabors’s lobbyist. It was then that Rangel made a commitment to oppose the bill that had passed the Senate that would eliminate the loophole. Several days later, a check for $100,000 arrived at the City University.

That kind of conduct, suggestive of a

quid pro quo,

would seem to cross the kind of basic ethical line that most people would recognize. But Charlie Rangel seems to have vaulted way over that line time after time. Here are some of the violations he has been accused of:

New York State’s rent stabilization law controls the rent landlords can charge for primary residences in certain buildings. To be eligible for a stabilized rent, the apartment must be your primary residence.

But as the

New York Times

disclosed, Charlie Rangel has four of them, all in the same building. He gets these 2500 square feet of Manhattan apartment at half price.

One of his four rent-stabilized apartments was used as a district office, which he paid for with taxpayer money. His landlord, eager to curry favor with him, hasn’t challenged his reduced rent.

And for several years Rangel had a fifth primary residence. He got a homestead exemption on his property taxes for a house in Washington, saying that this too was his primary residence and that he paid taxes there—neither of which is true.

Asked about these shenanigans, Rangel retorted angrily that where he lived was nobody’s business.

327

Rangel bought a vacation villa in the Dominican Republic and forgot to report $75,000 in rental income from the property on his taxes. Now, remember, as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, this is the man who writes the nation’s tax laws. How could he forget such a thing?

Unbelievably, he has blamed his failure to report these taxes, at least in part, on language problems, because the residents of the Dominican Republic speak Spanish. Then again, so does half of Rangel’s district. If anyone could have found a translator, presumably it was Charlie Rangel.

All of these issues are now before the House Ethics Committee for investigation. But given the record of that august body, we’re none too hopeful. In July 2008, Speaker Pelosi pledged that the matters would be dealt with quickly. It’s April 2009 as we write this—and still nothing has happened.

Like Chris Dodd, Charlie Rangel has gotten exceptional housing at a cut rate. And, like Dodd, he has depended on AIG and the big banks and investment companies to fund his campaigns while masquerading as a populist attacking them. Both of their futures are before their respective Ethics

Committees. But, more than that, it will be up to the voters to determine their fates.

ACTION AGENDA

If you have a problem with Rangel’s conduct, let Nancy Pelosi know about it and demand that he be removed as chairman of the Ways and Means committee. She can be reached at: 202-224-3121.

THERE IS NOTHING LIKE A NAME

Ted Kennedy, Jr., the Senator’s Son

Some people may insinuate that I am looking to trade on my family name. This is definitely not the case.

—

TED KENNEDY, JR

., April 2004

Apparently Caroline Kennedy isn’t the only member of the Kennedy family who’s tried to capitalize on her famous last name. Even before her disastrous attempt to be appointed as Hillary Clinton’s successor in the Senate, her cousin, Ted Kennedy, Jr., was one big step ahead of her. For years, Kennedy Jr. has been boldly exploiting both his name and his intimate relationship with the most influential member of the U.S. Senate when it comes to health care and organized labor: his father, Senator Ted Kennedy.

Those twin pillars of special interests—the health care establishment and labor unions—have been the foundation of Ted Kennedy, Jr.’s, phenomenal success in the last decade. And his father has been all too willing to help out in making the family connection into a lucrative business for his son.

Despite his righteous denials, public reports and anecdotal information indicate that Ted Kennedy, Jr., actually does privately trade on his famous family name.

Now that his father is set to be the quarterback on health care reform, Ted Kennedy, Jr., is positioned to be in the right place at the right time. His “health care advisory” firm, the Marwood Group, is busily offering its services to hedge funds and other interested groups in the United States and overseas.

What does Marwood offer? Advice and information on what to expect from Washington on health care reform and any and all issues that relate to the health care industry.

What makes Marwood so well equipped to sell this advice?

At the very least, the perception that its information comes straight from the chairman of the committee that will determine every single detail of health care reform. Beyond that, the perception that paying Ted Kennedy, Jr.’s, firm might give you unparalleled access to Senator Ted Kennedy, Sr.

Needless to say, most hedge funds (and lots of other businesses) would jump at the opportunity to have the inside scoop on which businesses will benefit and which will suffer because of the radical changes that are currently being considered for the health care system. Any clues, about the regulation of drugs, medical devices, nursing homes, hospitals, insurance companies, the biotech industry, and so on can mean a gain or loss to those industries and to the hedge funds that invest in them. An early heads-up can lead to immediate trading—buying, selling, shorting. That kind of information is a gold mine.

And Ted Kennedy, Jr., understands that completely. While there is nothing illegal about Kennedy Jr.’s activities and no evidence of any leaking of insider information by Senator Kennedy, the health care industry is desperate for any information and advice, and he knows it.

MAKING THE MOST OF FAMILY TIES

Looking back, it seems rather obvious: sometime around 2000, Ted Kennedy, Jr., apparently decided to begin to commercialize his unique and very valuable family contact in the Senate. Why not? It’s a cardinal rule of business: you use what you have.

To get the ball rolling, Kennedy Jr.’s firm, the Marwood Group, hung out its shingle and registered to lobby in Washington for the four years from 2001 to 2004. Not surprisingly, all of its clients came from a single sector of the economy: health care. For almost half that period, starting in June 2001, Kennedy’s father was the chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. That turned out to be extremely helpful to Ted Jr.

Whether you agree with Ted Kennedy or not, he has been a consistent champion of universal health care for more than twenty years and an influential voice for children, the elderly, consumers, and those without their own lobbyist in Washington.

His son, however, has followed a different agenda.

Ted Kennedy, Jr., went to Washington for one reason: to make money. He wasn’t there to be a devoted public servant or a tireless advocate for the poor and the downtrodden. He paid little heed to the familiar Kennedy family mantra about the importance of service to our nation and its people. To be clear: Ted Kennedy, Jr.’s, firm was not working on legislation to protect consumer interests or the public interest. Far from it: the Marwood Group was a lobbyist for big health care businesses—whose interests were, in many cases, directly adverse to those of consumers.

And what was Ted Jr.’s unique selling proposition? Well, how many other lobbying firms can deliver the chairman of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions to a meeting?

Take a look at who paid them. One of the firm’s first clients was the mega-pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS). That’s a pretty big fish to land for a new firm with no track record. Then again, if your father is the Senate’s leader in health care, chairs one of the key committees, and has access to information about what’s going on about congressional interest in the regulation of drugs, it’s a good investment for any drug company.

And BMS needed all the help it could get. The company had an urgent issue before Congress that was worth literally billions of dollars. To protect its profits, BMS was pulling out all the stops to try to pull off a major legislative feat.

When BMS hired Ted Jr.’s firm in 2001, it was engaged in a monumental lobbying effort to try to extend the patent on its runaway success drug, Glucophage, which was designed to control adult-onset diabetes. Although

BMS’s patent was due to run out in late 2001, the company was trying to benefit from a possible loophole in the patent law that might allow it to extend the patent for three more years and prevent other companies from selling a less expensive generic alternative. The loophole was a long shot, and the clock was ticking: the firm had only a few months to convince Congress to grant it the extension and keep its competitors from knocking down its doors.

To say this was worth a lot to BMS would be a prodigious understatement: In the year 2000 alone, sales of Glucophage amounted to

more than $3 billion!

328

If other companies were allowed to compete against BMS with low-priced generics, that $3 billion would be out the window. Of course, the company spent little time worrying about the drug’s burdensome price to consumers, who had filled 25 million Glucophage prescriptions in 2000.

329

That wasn’t its concern.

But someone at BMS

should

have been focusing on it. According to the public interest lobbying organization Congress Watch, extending the patent and continuing BMS’s exclusive right to produce the drug would cost consumers millions of dollars. Congress Watch dramatically described the potential financial effect, based on a formula created by the FDA:

Every minute that generic versions of Glucophage are not available adds an additional $1,000 to consumers’ prescription drug bills. Every hour costs consumers an additional $61,540. Every day costs consumers nearly $1.5 million extra. The six-month costs to consumers are $269 million. And the three-and-a-half year costs to consumers, should BMS succeed in its attempt to extend the Glucophage patent, would be $1.9 billion.

330

In the fight to maintain total control over selling the drug, money was no object for BMS. In 2001, the company spent $4.9 million on lobbying to try to get the Glucophage patent extended.

331

Before Marwood arrived on the scene, BMS had relied on the most prominent and influential lobbying firms in town to try to convince Congress to buy their position. So why did it suddenly hire an inexperienced little firm late in the year?

In part because, by late 2001, BMS wanted to sit down with Senator Ted

Kennedy, who had assumed the chairmanship of the health committee that June. Where was the best place to go for that? To Marwood, of course. And that’s what BMS did. According to the

Washington Post

:

The manufacturer, which spent $2.6 million on lobbying during the first six months of this year, retained Republican Haley Barbour and Democrat Thomas Boggs to contact key lawmakers.

Bristol-Myers also arranged for a meeting between company President Peter Dolan and Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) through the senator’s son, Ted Kennedy Jr., a lobbyist.

332

[emphasis added]

Actually, Ted Kennedy, Jr., never registered to lobby for BMS, but others in his firm did. It’s not clear why Ted Jr. didn’t register himself. Maybe he wanted to avoid public scrutiny of this eyebrow-raising transaction, in which the son of a senator was paid $20,000 for merely arranging a meeting for his father with the head of a corporation lobbying for special-interest legislation—a new low in lobbying annals, even by Washington’s extremely low standards. Even if he wasn’t registered, though, it’s reasonable to conclude that Kennedy Jr. was the one who did the key “work”—arranging the meeting between the BMS president and his father that was so crucial to BMS.

And Ted Kennedy, Jr., wonders why some people believe he trades on his famous name?

The BMS fee was a good one, considering the fact that it likely involved only a few minutes of time. After all, how long can it take to call your father and ask him to meet with one of your clients? For this, Marwood was paid $20,000 in 2001—a paltry amount to BMS but a full one-quarter of the Marwood Group’s lobbying fees for its first year. Not bad for just scheduling a meeting.

Surprisingly, though, in its 2001 lobbying disclosure form Marwood claimed it had made no contacts with the House of Representatives, the Senate, or any federal agency. No contacts with the federal government? So how did BMS manage to get that meeting with the elder Kennedy? And what

was

it paying Marwood to do? You don’t hire a registered Washington lobbying firm if it isn’t going to do any lobbying for you.

What’s also interesting about Marwood’s 2001 disclosure form is that it doesn’t admit to any involvement in the BMS patent issue. Under the section that requires a lobbying firm to describe the specific issues it lobbied on for BMS, Marwood wrote:

Provide advice re: grassroots program and work with provider team to help identify emerging biotechnologies and products.

333

Say what?

“

Grassroots

program”? What were they going to do—organize spontaneous community opposition to lower prescription prices on Glucophage? And “identify emerging biotechnologies”? Are they kidding?

How about “use your family position to sell a meeting with your father and the president of BMS to try and help BMS hold on to its billion-dollar patent”? How about “help us hang on to our pharmaceutical patents”?

Every other lobbying firm that BMS hired in 2001 listed specific bills and/or issues it had been hired to lobby for or against. Most of them related to the extension of the Glucophage patent. And significantly, BMS itself did not list “emerging biotechnologies and products” in its meticulous twenty-nine-page year-end disclosure of the issues it had lobbied on in 2001.

Marwood listed two lobbyists on its BMS disclosure form—yet those lobbyists apparently never lobbied for BMS or contacted anyone on behalf of the drug company, if we’re to believe its statement that it never contacted Congress or any federal agency. So why were they listed as lobbyists? One of them was Ted Kennedy, Jr.’s, partner in forming the firm, John Moore, a former political operative in New York governor George Pataki’s administration. What did they do for BMS? If they weren’t contacting any federal officials, why did they file a lobbying disclosure form?

Yet there were no inquiries made about any of these dubious disclosures. Why? Sadly, that’s business as usual in Washington. Congress has never wanted to regulate lobbyists, and it ignores even the most patently ridiculous filings. At that time, although the filings were public, they weren’t available online, and few people would have bothered to make the trip to Washington to sift through them.

One has to ask why Marwood was initially hired by BMS. It certainly

wasn’t because of the firm’s political skills and lobbying expertise—as a brand-new firm, it hadn’t developed any. But then again, it didn’t

need

any. It was apparently hired for a simple, raw political reason: to pay the son of a senator to arrange for a private meeting of great importance to a company with a matter of great economic concern. BMS had already hired many of the top-tier lobbyists in Washington; it didn’t need the lobbying services of the new kids on the block.

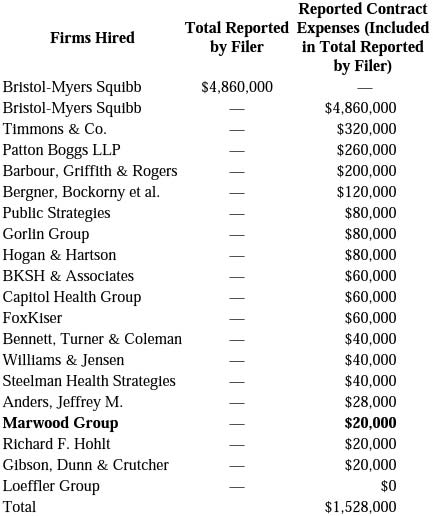

To understand the breadth of lobbying done by BMS at the time it hired Marwood, here’s a list of BMS’s lobbying expenditures in 2001:

2001 ITEMIZED LOBBYING EXPENSES FOR BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB

Source:

“2001 Itemized Lobbying Expenses for Bristol-Myers Squibb,” Center for Responsive Politics, www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientsum.php?lname=Bristol-Myers+Squibb&year=2008.

BMS was spending more than $6 million to lobby Congress and federal agencies that year. Did it really need to pay an extra $20,000 to Marwood

?

One wonders exactly what each of those lobbying groups was paid to do for BMS—especially the other firms that were paid only $20,000. Did they, too, set up special meetings for BMS? Whatever anyone else did for the pharmaceutical giant, it’s obvious that Marwood wasn’t hired to be the key substantive lobbyist for BMS.